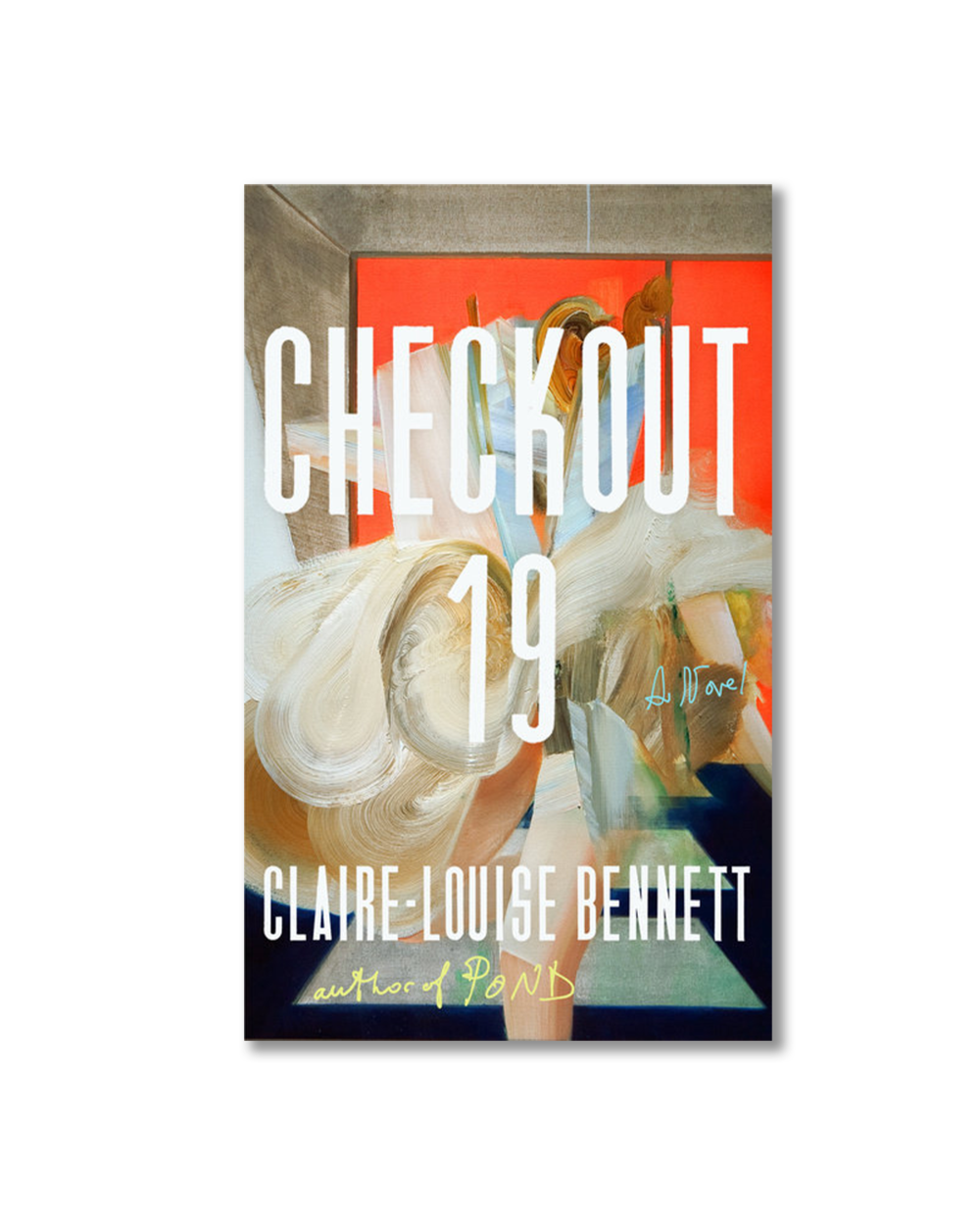

The Persistence of Little Words: On Claire-Louise Bennett's "Checkout 19"

Claire-Louise Bennett | Checkout 19 | Riverhead Books | 2022 | 288 Pages

It would be easy to say Claire-Louise Bennett’s second novel, Checkout 19, is a love letter to books. The book itself abounds with literary reference—from Blake to Bellow to Rhys—and each chapter is headed by a quotation—from the likes of Anaïs Nin and Ingeborg Bachman and John Milton—avowing to the life, mystery, and magic of the written word. Her line, occuring late in the book’s pages and posted in red letters on its flap, “We read in order to come to life,” is not so dissimilar from the oft-repeated Didion: “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.”

Like her debut, Pond, Bennett’s latest work distinguishes itself with a peculiar attention to language and detail that is both whimsical and punctilious, colloquial and coy. Tracing the life of a writer from her first encounters with books, Checkout 19 is bursting with anecdote. It is a book telling stories about telling stories—those remembered, retold, written down, and made up—where the line between what’s imagined, what’s happened, why it matters and what matters anyhow is continually teased and obscured. Writing and literature are central themes in their own right and a become way in which the narrator recalls her own memories, the two being intertwined.

As much as Checkout 19 is a book about books, story about story, it also bucks up against the very idea of story altogether. The “story” of the unnamed narrator’s life, which we could say this novel tells, is both laden with concrete detail—the many books she borrowed from the library as a child, the many times she nibbled on blocks of cheese and generic market crackers in her former London attic—and mostly unknown, save for those details. Even she is referred to variously as “she,” “you,” “we,” and “I,” interchangeably and without notice.

What occupies most of the book is detail, stringent in its refusal to reveal more than the fact of itself, and extravagant in its profusion and eccentricity. There is an accumulation of minutiae without obvious explanation or symbolism—“My mouth tasted of cucumber and elastic bands. I had the urge to sing”—which often finalizes paragraphs and chapters. There are many longwinded lists—one of “nice things”: “Lace, opal, gypsophila, rose oil, meringue, gardenia, pearl powder, mink, sugared almonds, pas de chat…”—that carry on, one suspects, by the sounding of its own momentum. Then there are the bizarre and obsessive, even grotesque imaginings that proceed by pages and appear and disappear without much ado. Apparently possessed, a woman in a grocery store reaches her mouth to the two raised fingers of her husband until she feels the “tips of the fingers come into contact with the back of her throat, sending sudden fluid up, up, to revel in the crescents of her eyes.” She describes “legs tickling incessantly” against her heart which, as she read, “lifted away like the psychopathic teeth of a cartoon cog.”

The narrator imagines in details and the details only spur more details. “What were the stories I wrote?” she asks. “Little things.”

For Bennett, or at least her narrator, it seems these things—created or remembered—never die, and the act of remembering them incites continual provocation and expansion. Throughout, one feels the narrator is creating her stories out of midair and then immediately and insistently convincing herself and the reader of their veracity, sometimes by the expansion of their image and then sometimes by an emphasis on the embarrassing persistence of little words. As if answering her own authorial question in real time, Bennett writes, “What is she doing now? She is tilting her head to one side now.” Relaying the omnipresence of Little Clause and Big Claus on the family reading list, she writes, “That’s right. Mother loved that. Laughed her head off. She did actually.” Both stories and memories alike take on a hypothetical air, and the reader is often jarred when reminded of their past-ness; that they have either or both happened before and been told already—sometimes even within Checkout 19 itself. Rather than imagine, the reader is invited to, in James Wood’s words, “imagine someone imagining” or, in this case, maybe also re-imagining.

The narrator writes of her former boyfriend’s realization that he has in fact raped her: “Dale will curse, Dale will say ‘fuck, fuck,’” as if she is imagining what will happen instead of what already has. The simultaneous specificity of what Dale will do and say, and the suggestion by this “will” that he may have yet to do it at all begs the question of its position in reality. Bennett’s narrator’s attention to detail is bedeviled by its speculative nature. It is as if she both knows and has no idea.

Of the bed and breakfasts of Brighton, a few of which she peruses on a solo trip to the beach town, Bennett’s narrator declares: “You look up the steps see a chandelier and an aspidistra and polished brass and black and white tiles and a plush red carpet or perhaps pale blue.” The assured knowingness connoted by “these places,” is almost unnerved by the profusion of detail. She is neither speaking of one place in particular, not looking through its doors and up its stairs and describing what is there (there would be no wavering of the “pale blue” in that case), nor speaking to all places—the inundation and precision of detail impossible to confer onto such a vague reference. The narrator revels in her own imagination, maintaining its fortitude and assuredness, but also taunting the reader with the reminder that it is still mere conjecture. The passage, like many of Bennett’s, is less about its subject—B&Bs in Brighton—and more about the act of describing it. Description is both relished and ironized by the question of its usefulness (to what? Narrative?).

It seems that for Bennett there is an intimacy, secrecy, and perhaps even perversion to the act of noticing. A man at the supermarket lends the narrator, who stands perennially at the eponymous checkout 19, a copy of Nietchze’s Beyond Good and Evil because, as she notices, her hands are clasped just like the woman’s on the cover. When the first story the narrator ever wrote, in the back of workbook as a schoolgirl, is uncovered by her teacher, she is both embarrassingly shy and titillated. “He’d gone somewhere he shouldn’t have gone, and found something curious there. A curious little story, he said.” A secret becomes a secret even as it exists, like her hands, in more or less plain sight. It is not the exposure that matters, not the revelation, but fine attention that makes something seen, and then, coveted.

Yet, the effort to say or describe something exactly right, to acknowledge its being seen, is both futile and never-ending, infinitesimally provoking. “For goodness sake spit it out,” Bennett’s narrator chides herself. In quick succession, she appears to dither between lofty verbosity and colloquial, knowingly evasive shorthand: “Quashed completely by deep despair and anxiety which was relieved now and then by anguished though relatively merciful bouts of sobbing.” This high-brow volubility becomes the butt of “sobbing’s” joke as it delights in its bathos; it all came to nothing more than the usual. Neither method appears to adequately satisfy while both appear to mock the other, though this doesn’t mean Bennett or her narrator won’t keep trying (maybe despite herself?). Referring to books by women written when they were “sad,” the narrator interjects: “and when I say sad I’m being coy of course, but what else can I say? Adrift?” Literature itself is treated similarly. It is both a kind of magic, a “key to infinite lightness” which has the omnipresent power to “turn the pages” of “one’s entire life,” and so commonplace to the extent that it is not sacrosanct to refer to it as a “dud.”

At times, Checkout 19 veers into explicit and heady symbolism. The story of Tarquin Superbus could be mostly for the purpose of speaking to the power and life of even a single sentence. A sentence—in this case one hidden in the countless books which fill Tarquin Superbus’s library and which he never opened to realize they were all blank—remains particular to, and visible only to the reader. When the narrator’s own writing is set aflame by a jealous former boyfriend, she reflects, “I couldn’t quite discard the idea that in it somewhere there might have been a sentence, just one sentence, of such transcendent brilliance it could have blown the world away.” One a little less dizzily absorbed by the literary world could suppose a book about books a little haughty and insular.

Bennett’s ultimate design, though, is not to be read so earnestly. What turns Checkout 19’s screw is the acute self-awareness of how things are said, that everything said is a commentary on how it’s said and not for the proposition that it is somehow right or wrong. Hyper-consciousness of language means one is constantly reminded of its artifice, its thing-ness, the sound it makes, and that it makes a sound at all. A sentence can be both magical and “not bad” not because of what it explicitly points to beyond or symbolizes, but for the miracle that it can exist for its own sake all the same.