The Ineffable, the Unspeakable, and the Inspirational: A Grammar

The theme of the 2022 Cleveland Humanities Festival is “Discourse.” Zach Savich, a Cleveland Review of Books board member and associate professor at the Cleveland Institute of Art, asked a group of artists, writers, and scholars from Cleveland and beyond to address the topic, “How is looking a form of discourse? Or: how does looking become discourse?” Their responses explore some of the ways in which private and shared experiences of vision contribute to culture, conversation, identity, and collective exchange.

Neuroscientists tell us that what comes to the retina of the eye is only a part—and not even the largest part—of what we see. Seeing is ”an active and creative process,” (1) embedded in layered systems of neural networking. It involves dynamically interacting pathways of simultaneous input and processing distributed across the brain. (2) In Principles of Neural Science—the standard neurology text for medical students—the authors marvel that “the visual system transforms transient light patterns on the retina into a coherent and stable interpretation of a three-dimensional world.” (3) What does the complex and fluid mechanism of seeing mean for “looking” at a work of art?

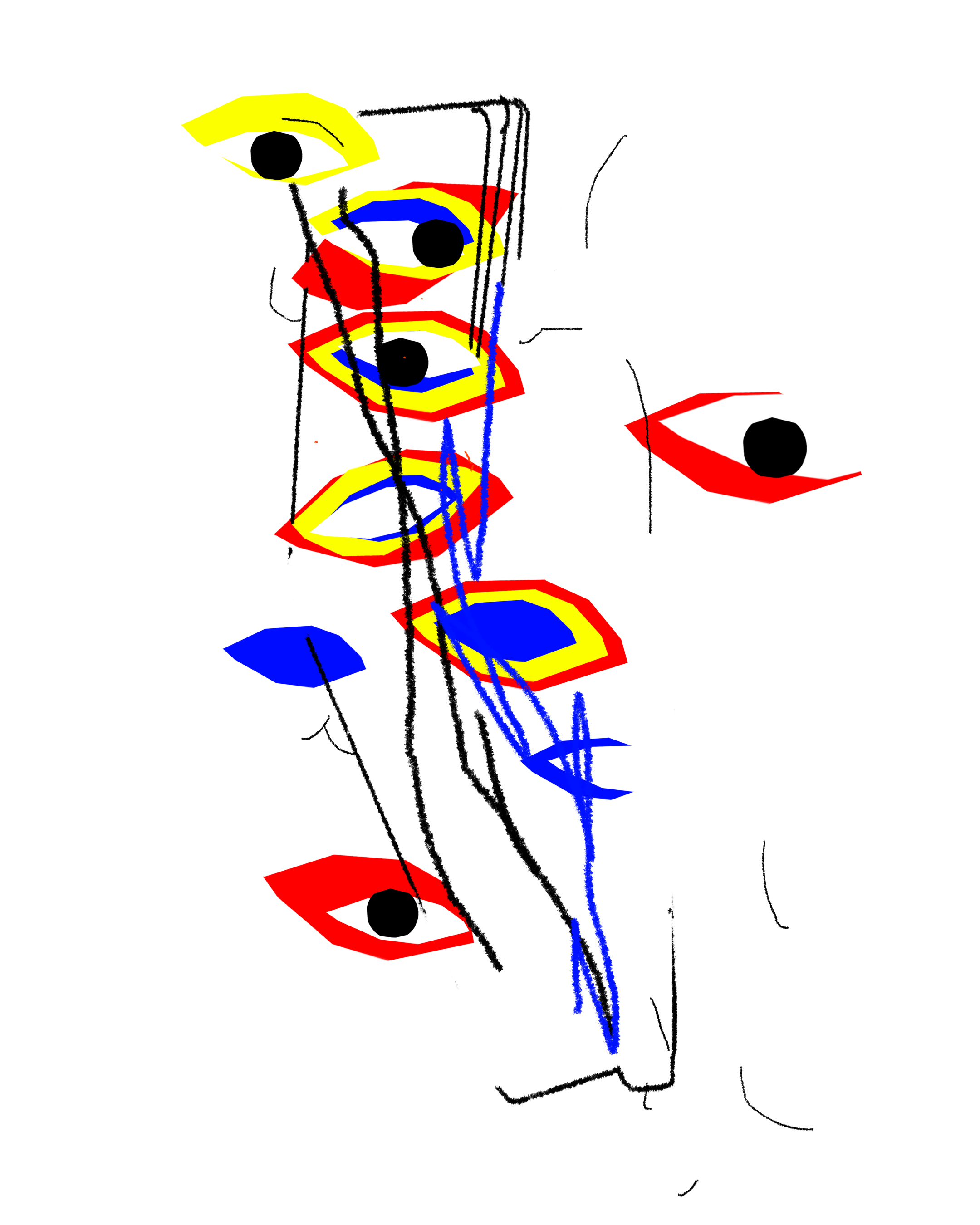

In an essay called “Motherwell’s Mother,” (4) I showed how abstract forms and compositional organizations in the art of Robert Motherwell have meanings that are specific and sufficiently elaborated to constitute an iconography of like representational images. These abstract forms articulate non-verbal thoughts and bring unconscious ideas into consciousness by giving them a tangible identity. The structural relationships between such forms constitute a grammar. In this essay, I want to build on the concept of an iconography in abstraction to address the discourse established through abstract forms and materials. This dynamic exchange permits artists not simply to represent but to engage with viewers discursively on non-verbal content.

The artists Alexander Calder and Joan Miró carried on just such a conversation through their work. Miró and Calder met in December of 1928, commencing a life-long friendship. Miró never learned English, but they managed a great deal of conviviality when they met and occasionally sent one another postcards and messages. They had in common only an awkward French, riddled with grammatical errors, (5) and yet a fluent, nuanced, and profound “conversation” took place through their work, and in particular through their use of materials. In the catalogue foreword to an exhibition of 2004 that paired these two great artists, their grandsons recounted the recent discovery of an old animal jawbone that Calder had inscribed and given to Miró. It was found in the Parellada Foundry where Miró had worked and where he had it cast (as a kind of “nose”) for his bronze sculpture, Maternité, of 1969 [fig.1]. (6)

Figure 1. Joan Miró, Maternité, 1969

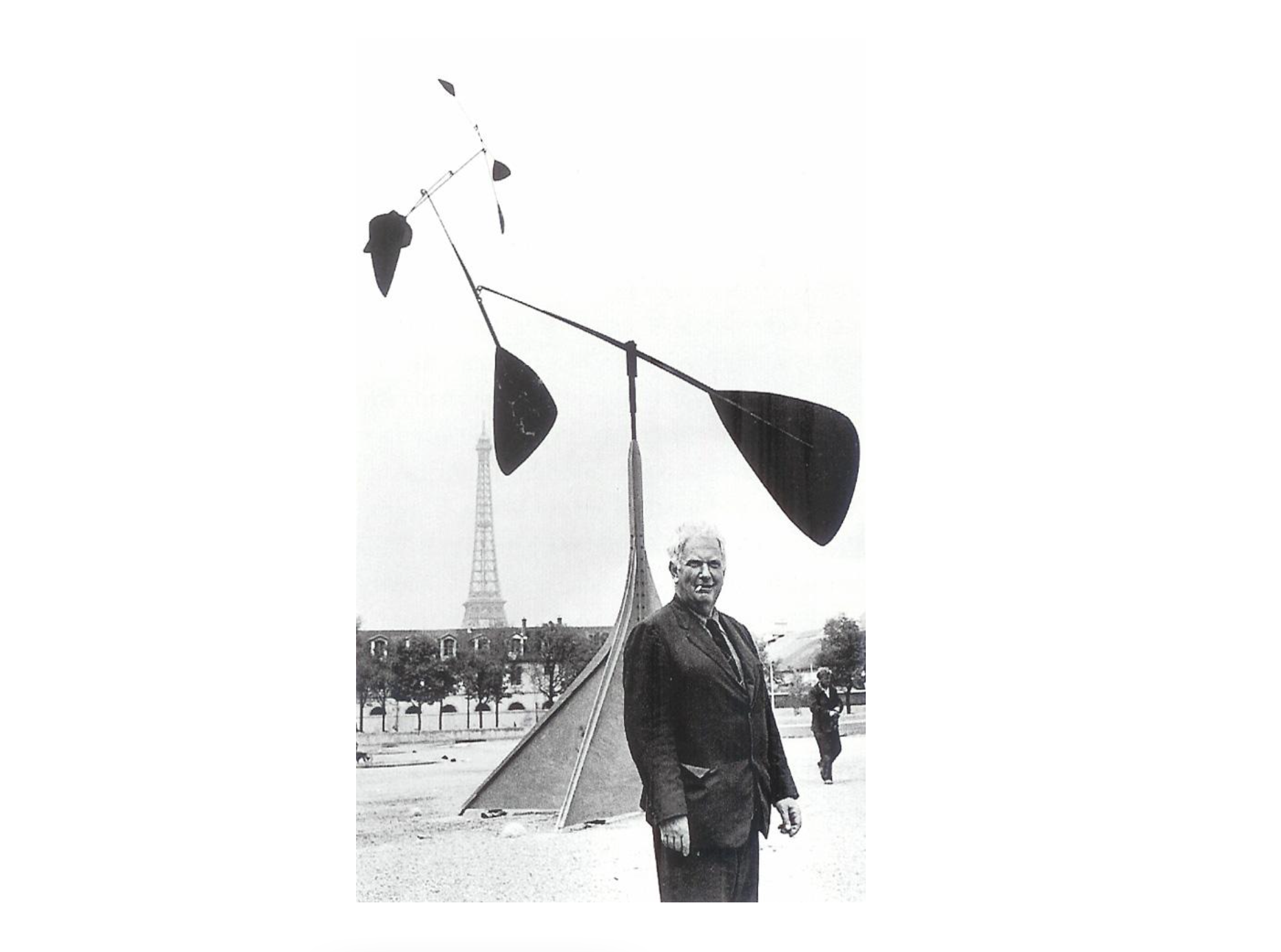

As with Miró’s work, everyone loves Calder’s sculptures. That his work should be, at the same time, among the most intellectually challenging art works of the 20th century is a conundrum designed to baffle categorizers. A great Calder mobile, like Sumac II of 1952 [fig.2], is so accessible on one level and yet so difficult to penetrate on another. In 1958, at UNESCO in Paris, Calder stood beside his just completed, standing mobile Spirale [fig.3], when an interviewer asked him if there was any symbolism in it. “There’s no history attached... sorry,” Calder replied, and his wife, Luisa, added: “Sandy is about as unsymbolic a person as I know.” (7)

Figure 2. Alexander Calder, Sumac II, 1952

Figure 3. Alexander Calder with Spirale, 1958

Calder never offered a verbal account of any deep meaning in any of his work, and to make matters still more complicated for the art historian, an irrepressible connection to the child-like keeps coming up. Calder himself remarked on this; looking back on his November 1964 retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, for example, he said, ironically: “There had been a few large stabiles and many very small objects suitable for children to bat and crush. To this, I attribute my success. My fan mail is enormous—everybody is under six.” (8)

The art historian Albert Elsen, struggling to articulate Calder’s achievement against this backdrop, called the mobiles “interactions of events” and perceptively pointed to their existential search for balance—literally and figuratively—as central to their meaning. He also cited this anecdote reported in the Atlantic Monthly, as though it were necessary to add gravitas by association: Albert Einstein went to the Museum of Modern Art in 1943 to see Calder's motorized sculpture, A Universe, of 1934 [fig.4], and after standing in front of it for forty-five minutes and waving away everyone who approached, Einstein reportedly muttered “I wish I had thought of that.” Elsen then quotes Calder speculating that Einstein was “waiting to see the same combinations come up again so that he could work out the ratios of the different parts. I had set the movements in a ratio, I think, of nine to ten, so that the whole machine had to do ninety cycles before it repeated itself.” Elsen remarks on Calder's ability to visualize a work that involved such complex compositional permutations among the parts, in cycles lasting as long as forty minutes; it was, he noted, an extraordinary feat of conceptualization. (9)

Figure 4. Alexander Calder, A Universe, 1934

But Calder was, after all, trained as an engineer and his albeit remarkable ability to conceptualize what he wanted to do in these terms is not a revelation of the symbolic content underlying it. Elsen went on to say that, “Calder’s vision has a certain innocence which, child-like, makes impossible analogies, is always optimistic, and regards its creations as self-evident in logic and meaning. There is no conscious symbolism in an art that is based on Calder’s principle of full disclosure.” (10) If Calder’s work seems at first “self-evident in logic and meaning,” this is a subterfuge for work that is deeply engaged in a sophisticated, if intuitive, investigation of man’s place in nature and of Calder’s own psyche.

Like so many of Calder’s works, his 1950 mobile Numbered One to Seven [fig.5] has a disarming simplicity to its title. It describes two sides of a numerical equation—seven elements on each side, count them: “one to seven.” Calder made his Dog [fig.6] with the same directness out of a clothespin, a wooden dowel, and wire. He made it around 1940, though it belongs to a playful vein in his work that had begun with his Circus and toys in the 1920s and persevered to the end in humorous works like Nervous Wreck [fig.7]. The reference to childhood in the reception of the work of Calder takes impetus in part from the aspects of his style, methods, and materials that seem especially simple and spontaneous in expression. The palette of primary colors and the rudimentary construction in the mobiles and stabiles as well as the transformation of everyday found objects in a work such as Dog foster this association.

Left: Figure 5. Alexander Calder, Numbered One to Seven, 1950; Right: Figure 6. Alexander Calder, Dog, c. 1940

Figure 7. Alexander Calder, Nervous Wreck, 1976

Calder’s sister reported that, as a child, he was already predisposed with the same drive to “make things” (11) from scavenged scraps that characterized his mature career. On one occasion, she recalled, after a storm “which necessitated extensive repairs to telephone and electric wires, the eight-year-old Sandy triumphantly returned to his basement workshop bearing armfuls of copper wire scraps.” (12) This was understood by her and by others to prefigure the bricolage with which Calder constructed the performers in his wire Circus, works of found parts like Dog, and the continuing thread of unpretentious mechanical construction that persisted in mobiles right to the end of his career.

In addition to the untransformed materials, the flat, unmodulated color, and the reduction of the palette to primaries with black and white, Calder’s rudimentary twisting of wire into simple articulated joints, as can be seen in a close-up of Sumac II [fig.8], gives the impression of a naive lack of artifice in his sculpture. The undisguised, rough welds with which Calder tacked the pieces together also enhances the appearance of casualness in his process. Children, with less experience of the world, see objects with fewer preconceptions, putting them together and describing them in fresh and unexpected ways. Children also rely more on tactile experience: babies put things in their mouths, toddlers need to touch things.

Figure 8. Detail of Alexander Calder, Sumac II, 1952

Like so many great modern artists from Kandinsky and Klee to Rothko, (13) Calder and Miró aspired to reconnect with the childhood unconscious; they did this not to reduce the complexity of their subject matter but rather to probe it to a deeper level. In the first instance, Calder takes inspiration from the natural world, as in Sumac II and the Lobster Trap and Fish Tail (1939) [fig.9], and from his persistent fascination with the solar system, as in A Universe and his 1931 stabile Croisière (or Cruising) [fig.10]. He also took inspiration from mechanical devices such as the eighteenth and nineteenth century planetary models made for visualizing the universe.

Left: Figure 9. Alexander Calder, Croisière, 1931; Right: Figure 10. Alexander Calder, Lobster Trap and Fish Tail, 1939

Calder’s exploration of the cosmos, with its overwhelming scale, expresses the relentless curiosity and awestruck admiration of the scientist-engineer, which has certain affinities with the child in its openness and sense of wonder. Calder seems intent on mastering the solar system and in his sculpture we feel the powerful hands of this bear of a man showing us how to make it do what he wants. The insistently handmade, do-it-yourself style of Calder’s work evokes our memories of our childhood drive toward mastery and the fantasies of omnipotence in an imagined world where things mean what we want them to mean and where we can make them do anything we care to imagine.

Certain specific rites of passage in Calder’s life inform the cosmic themes. As a boy of seven, Calder had experienced a year-long separation from his parents when his father had gone to a sanitarium in Arizona seeking a dry climate for his tuberculosis. (14) In his Autobiography, Calder remembered his exhilaration at their reunion, stargazing under the clear night sky on the Arizona ranch. In another vivid memory, Calder recalled when, at the age of twenty-four, he hit a dead end in his engineering career and took time off to reflect. He signed up for a stint as a common seaman on a merchant ship heading through the Panama Canal and later condensed that period of soul-searching into a single memory of a night at sea—on a cruise (une Croisière): “It was early one morning,” he wrote, “on a calm sea, off Guatamala, when over my couch—a coil of rope—I saw the beginning of a fiery red sunrise on one side and the moon looking like a silver coin on the other... It left me with a lasting sensation of the solar system.” (15)

Neither Calder’s excitement at seeing the stars in the night sky over Arizona, nor this epiphany of the sublime in the dawn at sea seems to have evoked anything of the terror of the sublime that Edmund Burke famously described at the overwhelming power and scale of nature which reduces the individual to existential insignificance. (16) Instead, Calder describes the dawn on one side and the night sky on the other as a kind of equilibrium—like his mobiles. Calder brilliantly transformed what might have been an unsettling subject into something balanced and playful, instilling a sense of control and mastery.

Figure 11. Alexander Calder in front of Picasso’s Guernica and behind the Mercury Fountain, 1937

Yet, on occasion, Calder’s materials and his construction protocols intimate something else. In 1937, Calder made a Mercury Fountain for the Spanish Republican Pavilion at the Paris World’s Fair. A photograph of the period [fig.11] shows Calder standing behind his Mercury Fountain, with Picasso’s Guernica in the background. The Mercury Fountain has the same improvisational innocence of style in its construction as his mobiles. So how do we make sense of Calder’s Mercury Fountain in the program of the Spanish Republican Pavilion which was designed to condemn the rise of Francisco Franco's Nationalist army and to affirm the legitimacy of the Spanish Republic in the Spanish Civil War that was then raging? The architect Josep Lluís Sert commissioned three major works for inside the entrance to the building: Picasso’s 1937 Guernica (referring to the people of the little Spanish town whom the German Luftwaffe massacred earlier that year, testing its weapons in support of the fascist insurgency of General Franco), Miró’s angry painting of The Reaper (Catalan Peasant in Revolt) wielding a menacing scythe [fig.12], and Calder’s Mercury Fountain [fig.13].

Figure 12. Joan Miró, The Reaper (Catalan Peasant in Revolt), 1937, The Spanish Pavilion, Paris World’s Fair, destroyed

Figure 13. Alexander Calder, Mercury Fountain, 1937, reconstructed

Whereas Guernica and Miró’s Reaper are both monumental, grim and savage works of violence and protest, Calder’s Fountain outwardly has all the playfulness of his other mobiles. The mercury is pumped up from a pool at the bottom and trickles down from one large, leaf-like, sheet-metal trough into another, collecting in the pool at the bottom [fig.14]. The fountain rests on two arched pipes of the same linear profile as the pipe which spurts the mercury out at the top, giving the sculpture as a whole the delicate, attenuated form and suggested motility of a giant praying mantis. A long rod, with a paddle-shaped petal as a counterweight on one end, leans out balancing a finer line of black iron with mobile forms that dance on either end. A quivering wire script spelling out the word “Almadén,” hovers in the air, dangling off one end of this fine black line, and a single red spot—the only touch of color in the entire work—floats at the other end. On the stone rim of the pool, Calder inscribed “Spanish Mercury of Almadén,” referring again to the world’s most abundant, and centuries old, mercury mine, located in Spain between Madrid and Seville.

Figure 14. Detail of Alexander Calder, Mercury Fountain, 1937, reconstructed

The reference to the mercury mines at Almadén would have evoked then recent memories of Franco’s brutal subjugation of the 1934 Asturian miners’ uprising and of the commune of Almadén which rose in resistance to Franco’s fascist Nationalists. The dark, brooding heaviness of the mercury seems to express this ominous theme. Its mirrored surface is impenetrable. Pooling heavily in the black metal fronds of the insect and plant-like fountain and dripping with the viscosity of blood, the mercury gives this work an disquieting bodily atavism. The superficial playfulness of this piece draws us in and opens us up to a moment of innocent pleasure and in that unguarded state it turns to the unutterable chaos of the buried unconscious, as the materiality of the disturbingly unstable physicality of the mercury settles in. These primitive sensory memories take us to a darker place, to deep unspeakable meanings. (17)

As with Calder, Joan Miró and his work have been repeatedly described as child-like. In 1929 Michel Leiris—a writer and ethnographer who knew Miró well—talked about him as walking around wide-eyed like an “amazed child.” (18) In 1941 André Breton, the patriarch of Surrealism, characterized Miró as having “a certain arresting of his personality at an infantile stage.” (19) Miró was more forthcoming in verbal accounts of his work than Calder and gave us more representational imagery to examine. It is nevertheless hard to avoid thinking of a child’s openness in writing about Miró’s oeuvre too.

At first, the bright color and poetic lyricism of works like Hirondelle/Amour (Swallow/Love) of 1933 [fig.15], generated through spontaneous free association, like a doodle from line to word to form, evokes the liberated train of thought common in children. As with Calder’s work, the art of Joan Miró is widely popular and thought of as delightful, humorous, and innocently sympathetic by most non-specialists. Yet to serious scholars he was also “an artist of aggression,” as one curator recently wrote, “an artist of violence and resistance.” (20) Indeed, the revelation of a savage unspeakable content straight from the repressed unconscious is pervasive in his work.

Figure 15. Joan Miró, Hirondelle/Amour (Swallow/Love), 1933-34

While the works of Calder and Miró, more than those of any other major masters of the twentieth century, are persistently perceived as child-like, the childhood drawings of Calder and Miró are less fanciful, more soberly focused on mastering an account of reality than those of most children of comparable age. Miró’s 1901 Umbrella [fig.16] and other works done by him at the age of eight, like Calder’s childhood drawings, seem dryly descriptive. For all the charming awkwardness of Calder’s Self Portrait [fig.17], done at the age of nine, he represents himself matter-of-factly, on his knees with his tools lying on the floor beside him, sawing a piece of wood. The free play of childhood imagination that both artists seem to have expressed less than one might have expected when they were children, was assiduously cultivated and central to what marks them apart as adult artists.

Left: Figure 16. Alexander Calder, Self Portrait, 1907; Right: Figure 17. Joan Miró, Umbrella, 1901

In Miró’s works, like those of Calder, a deliberate exploration of child-like modalities of thought was already pervasive by the mid 1920s. Far from childlike, these works are deadly serious in their use of child-like procedures to explore unconscious content. In technique, Miró connects most profoundly with childhood in the appropriation and redefinition of found objects, and in the physicality of sculpture. “I have a need to mold things with my hands,” he told the curator James Johnson Sweeney in 1948, “to pick up a ball of damp clay like a child and to squeeze it.” (21)

Miró made his Tightrope Walker of 1970 [fig.18], from a mixture of modeled clay forms (like the ones in the upper left), an inverted baby doll, nails, and a perforated metal disc in the doll’s torso, all bound together into what he described at the time as an “unlikely marriage of recognizable forms.” (22) As in the cast pipe and the broken pot, the jawbone, and the molded forms in Maternité, the unlikeliness of the juxtapositions in Tightrope Walker is a Surrealist-inspired exploitation of free association to evoke poetic meaning and bring otherwise hidden unconscious thoughts into view.

Figure 18. Joan Miró, The Tightrope Walker, 1970

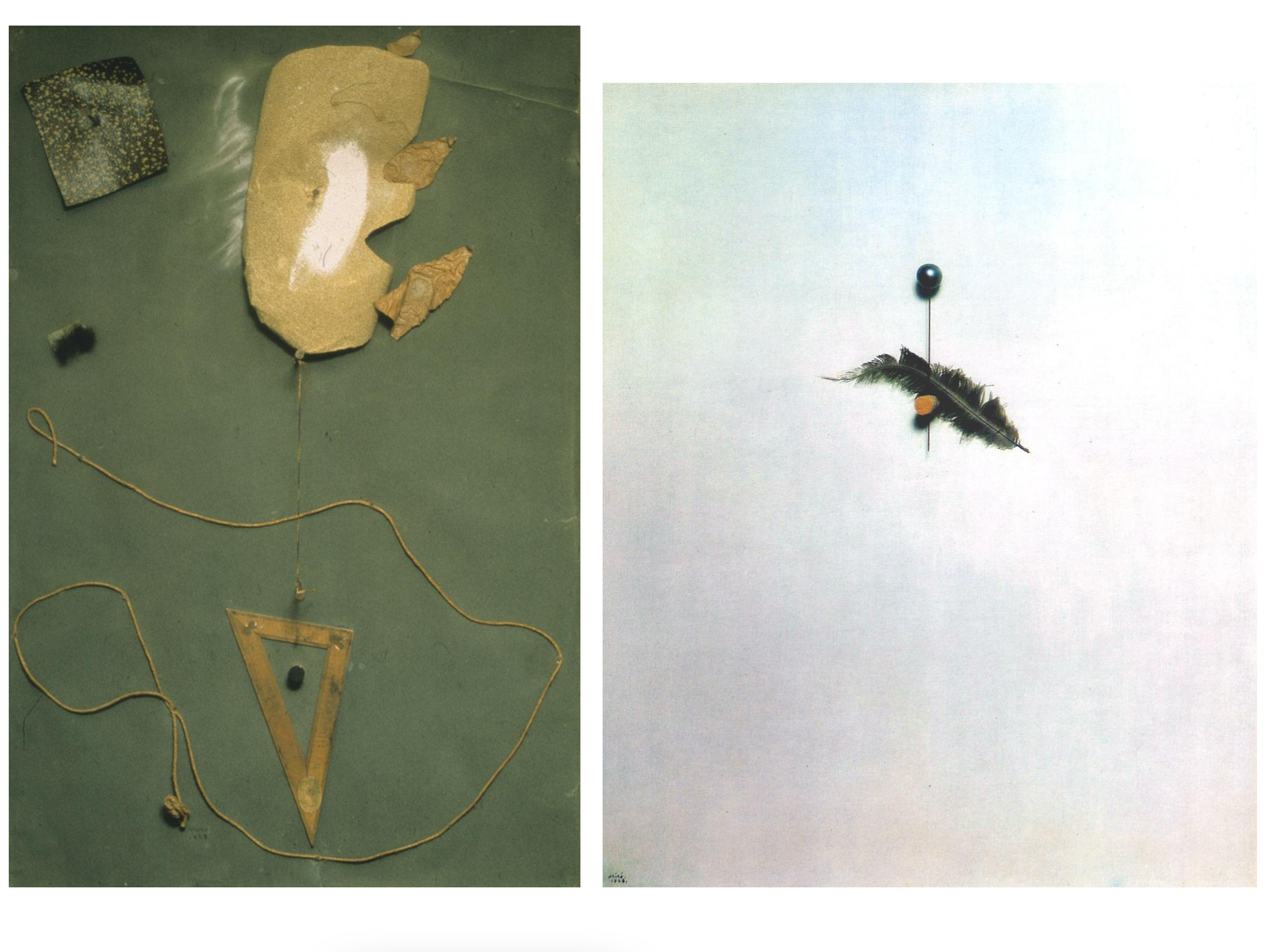

Miró began bronze casting and modeling in clay for the first time in 1944, but he had already started incorporating found materials into his work in the 1920s. He assembled The Spanish Dancer of 1928 [fig.19] from a scrap of sandpaper, string, nails, hair, an architect’s triangle, and paint on a sheet of flocked paper, mounted on a wood board. The 1928 Portrait of a Dancer [fig.20] consists of just a feather, a cork, and a hatpin on a painted panel.

Left: Figure 19. Joan Miró, The Spanish Dancer, 1928; Right: Figure 20. Joan Miró, Portrait of a Dancer, 1928

When Calder visited Miró’s Montmartre studio for the first time in December of 1928, he focused right away on the materials in Miró’s new work and on Miró’s poetic process of intuitive construction. Calder’s account of this first visit, in his Autobiography, centers on a work Miró showed him that consisted, as Calder recalled, of “a big sheet of heavy gray cardboard with a feather, a cork, and a picture postcard glued to it. There were probably a few dotted lines, but I have forgotten. I was nonplused; it did not look like art to me.” (23)

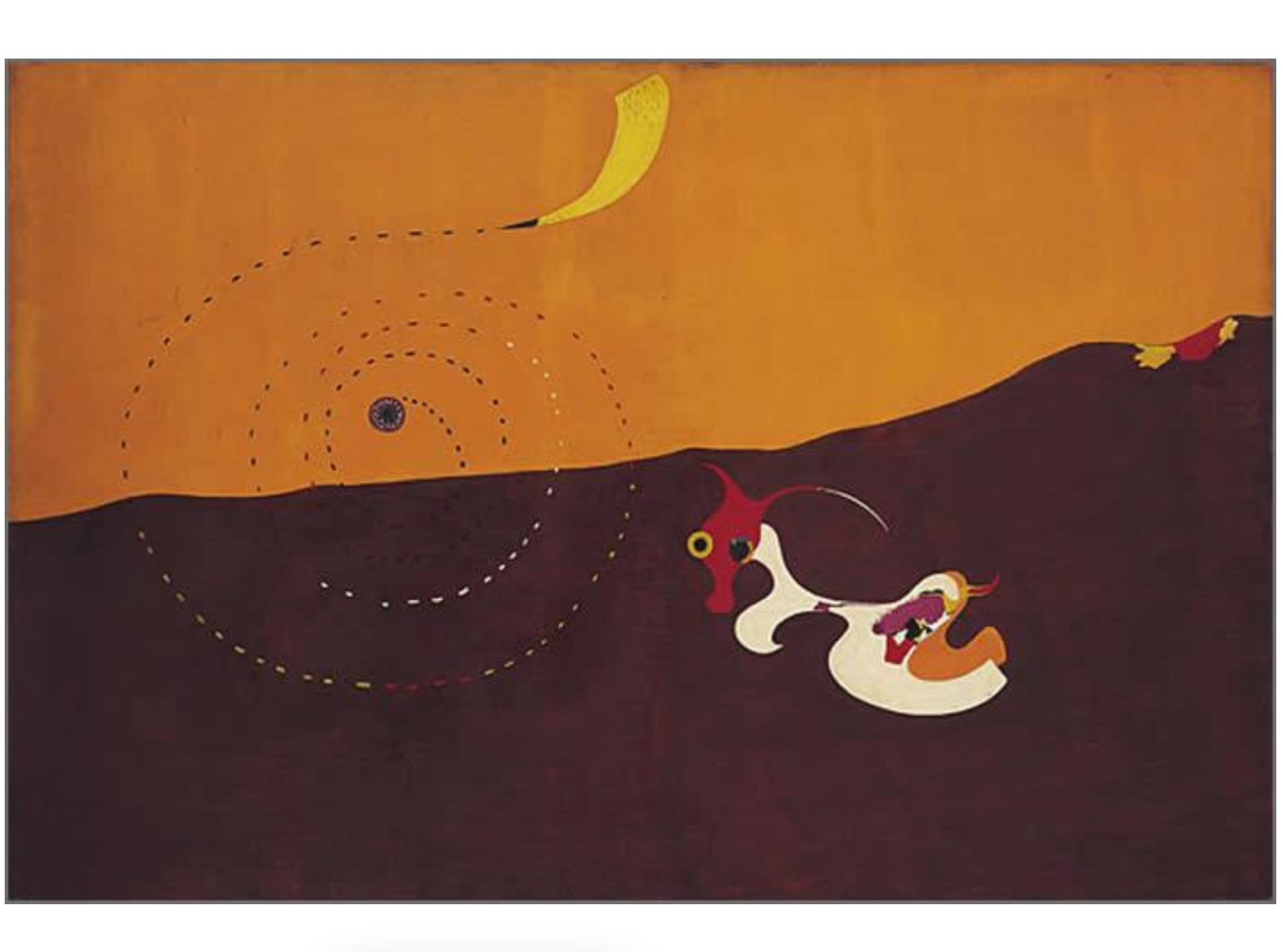

The work Calder remembered was certainly Portrait of a Dancer; no other work remotely resembles this description. But over the intervening years—between his first visit to the studio in 1928 and the Autobiography, which he dictated to his son-in-law nearly forty years later—Calder appears to have conflated the work with one of the later postcard paintings, such as Drawing-Collage of September 25, 1933 [fig.21]. (24) Miró used the trajectories of broken lines in several paintings of the time, such as Landscape Autumn (The Hare) of 1927 [fig.22]. (25) The dotted lines create a radical shift in language within the composition from the landscape and the rabbit, which are representational (however abstracted), to diagrammatic notation like the broken line of the bird’s spiral flight path. He meant these works to be read like poems with the symbols and images functioning on the same symbolic plane, juxtaposed rather than narratively laid out.

Figure 21. Joan Miró, Drawing-Collage, 1933

Figure 22. Joan Miró, Landscape Autumn (The Hare), 1927

What struck Calder most in this first encounter of 1928, as he described it, was the unconventionality in Miró’s use of materials. In Portrait of a Dancer, the materials so surprised Calder as to make the work “not look like art” at all. The conjunction in memory of the Portrait of a Dancer with works like Landscape Autumn and the postcard paintings (which he had to have seen at least half a dozen years later) suggests that something in these works connected them in a fundamental way in Calder’s mind and that a related sensation of surprise with regard to the materials and syntax occurred again for Calder when he first saw the paintings with postcards and perhaps also when he first saw the semiotic shifts in paintings like Landscape Autumn. Miró, by the way, also said of Calder’s work that: “When I first saw Calder’s art very long ago, I thought it was good, but not art.” (26)

Rather than borrowing motifs or techniques from one another over the course of their forty-five year friendship, the nature of the exchange between Calder and Miró seems to have had more to do with the surprise each experienced in the spontaneity of the other’s unconventional methods and materials. That sense of surprise continued to open up deeper and deeper content, each in the other. This aspect of their ongoing encounters with one another’s work pushed both of them, I think, to venture further toward the boundary of where art and “not art” meet, into a kind of radical disjunctiveness.

“For me,” Miro told an interviewer in 1959, “an object is alive... This bottle, this glass, a big stone on a deserted beach—these are immobile things, but they unleash a tremendous movement in my mind... As Kant said, it is a sudden irruption of the infinite into the finite.” (27) The disconcerting materiality in works like Miró’s Spanish Dancer and Portrait of a Dancer seem to have prompted that “sudden irruption,” reconnecting artist and viewer alike not only to an external infinite but to the internal depths of the preverbal world of early body memory and sensation in the unconscious. As Miró told the French critic Dora Vallier in 1960, “the older I get and the more I master the medium, the more I return to my earliest experiences. I think that at the end of my life I will recover all the force of my childhood.” (28)

Figure 23. Joan Miró, Shooting Star, 1938

In Miró’s 1938 painting Shooting Star [fig.23], the figures seem to emerge from a polymorphous field of erotic, tactile, color sensations. Beyond the superficial exuberance of its color and the freedom of its formal invention, this painting, like most of Miró’s work, is also filled with an unsettling bodily instinctuality. That tendency is still more evident in a work like Miró’s March 1937 charcoal drawing of a Nude Ascending the Staircase [fig.24]. The Nude is beautiful and grotesque at the same time, with unutterable revelations of the unconscious in the distortion of the figure’s bodily attributes. This is the duality of the beautiful; it is beautiful precisely because it gives formal control and organization to the grotesqueness of the uncontrolled in the repressed unconscious.

Figure 24. Joan Miró, Nude Ascending the Staircase, 1937

Miró’s nude goes, conceptually, in the opposite direction from Marcel Duchamp’s famous Nude Descending a Staircase of 1912, on which it comments ironically. Whereas Duchamp dehumanized the body into mechanized movement, Miró accentuated the organic qualities of the body. “I often work with my fingers,” Miró reported, emphasizing tactile memory. “I feel the need to dive into the physical reality of the ink, the pigment. I have to get smeared with it from head to foot.” (29)

Picasso provides a brilliant gloss on this dynamic of visual mastery with a particularly detached clarity in a drawing of 1933 called The Studio [fig.25] in which the living model overflows with a simultaneously delicious and repulsive, all-too-real vulgarity, while the painting of her on the easel is a classically idealized and formally controlled rendering of the nude female body. What Picasso illuminates in this drawing is the way in which the image represents the focus and order that permits us to tolerate, even to enjoy, the chaos, disorganization, and the bodily realism that belongs to the real model. In the Miró, the beauty of the draftsmanship helps us to overcome the disturbing reality of the subject. Picasso seems to suggest that on the easel the artist’s classicizing technique achieves this with regard to the living subject that is posed on the model stand beside him.

Figure 25. Pablo Picasso, The Studio, 1933

Figure 26. Alexander Calder, Wooden Bottle with Hairs, 1943

While on occasion one can also find explicit allusions to a more unsettling bodily reality even in Calder’s work, as in the Mercury Fountain or in his 1943 Wooden Bottle with Hairs [fig.26], our empathic relation to Calder’s sculpture mostly centers on the satisfying physicality of the process, on our fascination with the mechanics and materials, and on our wondering with him at the cosmos and at the beauty of nature. “I think best in wire,” (30) Calder told his sister Peggy, stressing his direct connection with his materials and their capacity to bring forms to life for him. The tangibility of the wire and wood seems to have evoked for Calder a palpable, psychic realism. The physicality of his work puts it in touch with the world of body sensation too and that gives it a deep feeling of authenticity. His formal playfulness and the physical act of bending the wire to his wishes pushes the spontaneous act of making to the foreground in works like Lobster Trap and Fish Tail, Croisière, Numbered One to Seven, and Sumac II, returning us to the empowering world of childhood fantasy.

Miró, on the other hand, uses the physicality of his work to look inward. “As for my means of expression,” he wrote in 1933, “I struggle more and more to achieve a maximum clarity, force, and plastic aggressiveness—in other words, to provoke an immediate physical sensation that will then make its way to the soul.” (31) Of course Miró’s work is also playful and exuberant on another level, and even when he turns to overtly “savage” subjects as he himself called them, his mastery of such overtly disturbing subject matter is exhilarating.

What is at stake in the work of both Calder and Miró is not a particular buried psychological subject or a specific childhood memory but a process of transformation. In Calder’s case, it is his breathtaking genius at overwhelming any revelation of the unconscious with a powerful focus on the process of making and mastering things and on the sensation of delight in doing so. He never appears to look inward. Whereas Miró deliberately exposes unconscious material and his innovative mastery over form, composition, color, balance—all the things that make a great painter’s work “great”—gives us that exhilarating sense of control in another way. What Miró saw on his first visit to Calder’s Paris studio was a performance of the Calder Circus that simply did not fit Miró’s mindset about the boundaries of what constitutes a work of art; Calder’s first sight of work in Miró’s studio pushed him out of his comfort zone with the use of what he saw inartistic materials. They both persistently did this for one another over the course of forty-five years, and they both continued to find the encounter thrilling. Whether it was Calder’s simplified two-dimensional planes violating their two-dimensionality by moving in three dimensional space or Miró’s stunningly base materiality, these artists each recognized that the other took them beyond the internal hierarchies of their own way of seeing. They continued to surprise one another and all surprises reverberate with revelations of the early unconscious.

My purpose, I have said, is not to interpret the iconography of particular works by Calder or Miró but to understand the grammar of visual thinking by looking at how these two artists constructed a dialogue with one another through forms and materials. Our inability to summarize either Miró’s Nude Ascending the Staircase or the most inspirationally optimistic of Calder’s mobiles, despite the vividness of our feelings about them, tells us something important about the nature of this grammar. “We are,” as Freud said, “unable to say what they represent to us.” (32)

Instead of reading writers for their ostensible subjects, Roland Barthes, in his book Sade, Fourier, Loyola, proposes for the writings of these three authors an intuitive, almost bodily acquisition of their content by following the rituals of each writer’s protocols of thinking. (33) He asks us to read the Marquis de Sade’s lists of tortures as a grammar with a syntax, to focus on the texture of Ignatius Loyola’s regimens in the Spiritual Exercises rather than on the questions and the answers he never receives in his conversation with God. It is by following the protocols of making in a Calder that we assimilate its meaning.

Most of us recognize from our personal experience that a variety of visceral sensations, impossible to verbalize, are commonly evoked by a deep encounter with a work of art. In describing his response to the Apollo Belvedere, the great eighteenth-century art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann wrote that “my chest seems to expand with veneration and to rise and heave...” (34) In a 1964 article for The Nation, exactly two hundred years later, Max Kozloff wrote that “ultimately, Pollock... gave visual flesh [my emphasis] to a whole era of consciousness in mid-century...” (35) Charles Baudelaire, in his review of the Salon of 1846, called the pictures of Horace Vernet a “brisk and frequent masturbation in paint, a kind of itching on the French skin...” (36) Miró wrote in a letter of 1922 that “When I paint, I caress what I am doing, and the effort to give these things an expressive life wears me out terribly. Sometimes after a work session I fall into a chair, totally exhausted, as though I had just made love!” (37)

The fact that a visual form can elicit such bodily sensations hints that works of art articulate body memory. The inaccessibility of art to verbal account leads me to the further surmise that this bodily experience may respond to the revelation of primary process—the term Freud gave to the preverbal world of primal bodily memory and repressed instinct in the unconscious. Something in the mechanisms of artistic expression allows the artist to overcome some of the barriers between the ego and the repressed. But the accessibility of the experience to the viewer implies not only that the viewer can also breach this wall in her or himself but, as Freud theorized in “Creative Writers and Day-Dreaming,” “the essential ars poetica lies in the technique of overcoming the feeling of repulsion in us which is undoubtedly connected with the barriers that rise between each single ego and the others.” (38) These barriers that encapsulate the ego also separate the conscious and the unconscious through repression, making it possible for the individual to interact with the social world. It is the pleasure in the beauty of the work, its mastery, that allows us to overcome the repression and explore that content.

A central thesis of the landmark work on creativity by Ernst Kris is that “the integrative functions of the ego include self-regulated regression and permit a combination of the most daring intellectual activity with the experience of passive receptiveness.” (39) Our sense that creative inspiration “just comes” to us, seems to confirm Kris’ observation of this regulated use of the repressed by the ego. As the ego of the artist delves into the unconscious, it exposes repressed material, incompatible with the ego. This clash produces anxiety, and such anxiety is familiar to all artists. They recognize it as part of the creative process and their willingness to tolerate it in order to make a work of art sets them apart from most other people. (40)

Writing to Michel Leiris, in 1929, Miró talks of the frustration of not having “the plastic means necessary to express myself; this causes me atrocious suffering…” (41) The American painter Phillip Guston described a similar anxiety to his friend Ross Feld, sometime around 1970. Feld had gone up to see Guston in his studio in Woodstock, New York and looking at a group of Guston's radical new figurative paintings [fig.27], he reported: “There was silence. After a while Guston took his thumbnail away from his teeth and said, 'People, you know, complain that it's horrifying. As if it's a picnic for me, who has to come in here every day and see them first thing. But what's the alternative? I'm trying to see how much I can stand.'“ (42) Even for Calder, this anxiety existed, though he attempted to dismiss it. A Life reporter asked if he ever felt sad and Calder replied: “No, I don't have the time. When I think I might start to, I fall asleep. I conserve energy that way.” (43)

Figure 27. Philip Guston, The Canvas, 1973

Sigmund Freud pointed out that the first ego is the body ego, derived from early bodily sensations. (44) The British psychoanalyst D. W. Winnicott described identity in terms of “true” and “false” selves, writing:

…the spontaneous gesture is the True Self in action. Only the True Self can be creative and only the True Self can feel real… The True Self comes from the aliveness of the body tissues and the working of body functions, including the heart’s action and breathing. It is closely linked to the idea of Primary Process, and is, at the beginning essentially not reactive to external stimuli,… The True Self appears as soon as there is any mental organization of the individual at all. (45)

Artists literally give form to perceptions and relationships that are too primal to be verbalized. As Robert Motherwell said, “through the act of painting I’m going to find out exactly how I feel.” (46) Freud was well aware that art opens an exceptionally traversable “path that leads back from phantasy to reality.” (47) The French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan emphasized the fluidity and ongoing dialogue with the bodily atavism of early memory as continuing throughout life. What he called the “family complexes” (models of interaction, like Freud’s “family romances”) are modified through life experience, he wrote, and these representations may re-enter the world of the unconscious and serve to reorganize the motile energies of primary process. (48)

Art also relies on this kind of introjection for both artist and viewer. The artist augments these representations not only with life experience but with a high degree of deliberate intervention in a conscious mode of organizing and contemplating experience as symbolized in form. The sculptor Jacques Lipchitz told Paul Dermé in 1920 that “the work of art should go from the unconscious to the conscious, and then finally to the unconscious again, like a natural, even though unexplainable, phenomenon.” (49)

The experience of art involves an integration of unconscious memory and energies with current events. Artists simultaneously reveal otherwise inaccessible unconscious material in the unique theater of their work and introject the formal structures they devise for this content back into the unconscious in the same manner as Lacan describes for his “family complexes.” The fluidity of this interchange and the way in which it continually modifies the individual’s unconscious organization—whether that individual is the artist or the viewer—is the key to what I am proposing here. Nearly half a century ago, Rudolf Arnheim made the point that the child artist uses art to examine and bring coherence to her or his encounter with the world. (50) The same is true for the adult artist. Charles Baudelaire’s famous remark that “genius is nothing more nor less than childhood regained at will,” (51) might, in psychoanalytic terms, be better understood as “childhood reintegrated,” because the kind of genius that pertains to the creativity of the artist involves first, a radical exposure—a general lowering of the artist’s psychic defenses so as to have liberal access to this material—and second, a newly coherent reorganizing of unconscious content, as represented in visual form.

Art exists on the edge of consciousness and has much in common with child’s play. The fantasy which directs a child’s play allows the child to lend every element a vivid sense of reality and to transform everything at hand into the necessary elements of the fantasy. This ability to reconfigure reality with total conviction annihilates semiotic categories, as, for example, in Miró’s Drawing-Collage of 1933, where we follow seamlessly the metamorphosis of the woman’s body from the psychic automatism of the line drawing to Miró’s use of a postcard for the head with a fancy hat. It also overcomes the fixity of meaning in objects, known through experience and reason, as in Calder’s Dog, where we accept without question the clothespin as a head. Art revitalizes our emotional connection to recognizable materials and objects by destabilizing their identity and thereby making them available for new meanings.

The act of genius that puts us in awe in such works is the artist’s ability to open the memories and modalities of childhood so profoundly and extensively, and to bring them into rapport with the artist’s current state of being. We are in awe because we all recognize ourselves in this exposure and in this reintegration; and we accept the exposure because of the pleasure and reassurance we derive from identifying with the agility with which the artist masters it. (52)

There is always a sense of discovery in art as we bring together unconscious thought and memory with present experience. Willem de Kooning remarked that: “there is no plot in painting. It's an occurrence which I discover by, and it has no message.” (53) Indeed, the signal innovation of the Abstract Expressionist painter is thinking in paint, rather than in pictures, though it was prefigured in Kandinsky’s pre-war abstraction and paralleled in the spontaneous use of materials in David Smith’s welding and in Calder’s construction. For de Kooning, “content is a glimpse of something,” he said, “an encounter like a flash.” (54) That epiphany of content, embodied in a form that cannot be verbalized, but is mastered through artistic process, is what we value most in a work of art.

One of the things that works of art do is to open the doors we have closed on aspects of our memory and thoughts. In that momentary opening, we not only re-experience normally undisclosed feelings, but we find ourselves able to reconnect them to the realities of both the present and the past in fresh ways, just as we may do with verbal insights that present themselves in the course of psychoanalysis. This highly charged experience that comes in the successful encounter with a work of art, always has the exhilarating sensation of surprise. (55) It involves the momentary exposure of the undefended material of the unconscious. The reorganization of the defenses in the artist is mirrored in the experience of the viewer. Friedrich Nietzsche wrote of the overwhelming power of a glimpse of such “truth” as eliciting nausea. (56) In Naked Lunch, William Burroughs wrote of this raw sense of exposure as: “a frozen moment when everyone sees what is on the end of every fork.” (57)

In The Ego and the Id of 1923, Freud rejected the idea that a cogent thought process, much less conscious intellectual work, could exist amidst the unruliness of visual experience because “the relations between the various elements of this subject-matter, which is what specially characterizes thoughts, cannot be given visual expression.” (58) I think that the discourse in form between Calder and Miró shows us otherwise. This is clear in each of their first encounters with the other’s work. Visual thinking can be innovative, rigorous, and conscious, without necessarily succumbing to verbal explanation. The greater proximity of visual expression to unconscious material is precisely what gives the best works of art their privileged sense of authenticity.

If we attempt to describe Miró’s Nude Ascending the Staircase to someone who isn’t looking at it, we can’t even come close to communicating in words what is communicated so vividly in visual form. Works of art give immediately recognizable form to experiences for which we do not quite have words. They create a discourse on these experiences through multiple simultaneous overlays of time and materiality, and other formal devices, in a metonymic construction like what Freud called the “dream work.” (59) This is commonly visible in children’s art and it is also a persevering remnant of early thought processes, present in the way in which adults—in particular, artists—organize and interpret their experience.

One of the outstanding features of visual thinking is that it fosters the reordering of experience in a way that reveals connections hidden or dismissed by verbal logic. Visual and verbal thinking coexist and interact in works of art, as they do in dreams; we pass fluidly back and forth in our thoughts from the metonymic to the metaphoric to the logical. For example, a woman familiar with psychoanalysis once remarked to an analyst in her acquaintance, of whom she was quite fond, “I had a dream last night and you were in it! I was playing the piano and you kept saying to me, ‘b-flat, b-flat!’” “B-flat” becomes “be flat,” unconsciously making clear her wish to be on the analyst’s couch, perhaps for more than an interpretation!

Visual thinking has the ability to bypass the conscious control of language in articulating experience and to tap directly into the language of primary process—that uncensored cauldron of repressed memory, body experience, and metonymic logic. (60) "I don't think one can explain it,” the English painter Francis Bacon told David Sylvester [fig.28]. “It would be like trying to explain the unconscious,” he said. “It's also always hopeless talking about painting—one never does anything but talk around it—because, if you could explain your painting, you would be explaining your instincts.” (61)

Figure 28. Francis Bacon, Self Portrait, 1969

In Against Architecture—a book centered on the writings of Georges Bataille—Denis Hollier pointed out that “the nameless is excluded from reproduction, which is above all the transmission of a name.” He then described Bataille as “relentlessly” attempting to achieve “the perverse linguistic desire to make what is unnameable appear within language itself.” (62) Hollier’s point is that Bataille introduces a powerful, disintegrating force that is intuitively recognizable and undeniable, yet it cannot be described fully in verbal language; he introduces this force into the very ordering and naming, the reproductive structure of language itself, thus thrusting language into a perpetual state of dynamic and disturbing instability from within.

The ineffable, the unspeakable, and the inspirational, are at the heart of the visual arts. There are no words to describe a work such as Miró’s Nude Ascending the Staircase in all its vivid repugnance and simultaneous beauty or the well of conflict in Bacon’s Self Portrait. No manner of words could reproduce the mixture of emotions—it is an almost bodily sensation of repulsion, mixed with the pleasure of mastery, that we experience if we really allow ourselves to dwell in these images. Viewers respond with revulsion to such an exposure of unconscious content in a work of art. Yet that uneasy encounter is at the essence of art and through mastery the viewer comes to erotize it.

Works of art articulate, in form, profoundly sensual feelings rooted in the most primitive level of bodily memory. Artistic beauty both invokes the pleasures of early bodily sensation, and it revisits unpleasure. Art contains that essential ambivalence, calling up deep resonances of the pleasure principle (63) and, at the same time, vulnerabilities and definitively unattainable longings, and this introduces a fundamental instability into the psychic organization. (64) Lacan points us to this implication of dynamic instability in Freud’s model, and to its essential open-endedness. (65)

The German painter Gerhard Richter has said:

A picture presents itself as the Unmanageable, the Illogical, the Meaningless. It demonstrates the endless multiplicity of aspects; it takes away our certainty, because it deprives a thing of its meaning and name. It shows us the thing in all the manifold significance and infinite variety that precludes the emergence of any single meaning and view. (66)

Part of what makes art so important to us is this destabilizing undecidability. Art opens areas of unconscious material otherwise inaccessibly shielded by a formidable system of psychic defenses, and in this moment of vulnerability, it creates a state of openness. What we experience as child-like in a work by Calder or Miró is precisely this. The motility of unconscious forces—their adaptability to the changing roles assigned them by shifting structures of unconscious representation and organization—allows the work of art to function as an organizing paradigm. Artists give their viewers a form with which to articulate experience for which neither viewer nor artist have, until that encounter with form, had a vocabulary. The fluid communication art provides between the unconscious and consciousness helps the individual (both artist and viewer) to regroup psychologically in response to the relentless pressure of change and conflict in the world. Moreover, the work of art offers itself not only to the artist but to anyone who is able to recognize what has been given form in the work. Art, like falling in love, simultaneously disorganizes and nurtures the self toward a creative reordering, (67) like a Calder mobile, perpetually regaining equilibrium in the constantly unpredictable currents of air.

(1) Eric R. Kandel, James H. Schwartz, and Thomas M. Jessell, Principles of Neural Science, 4th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2000), 493.

(2) “In vision, as in other mental operations, various otherwise unrelated attributes—motion, depth, form, and color—are all coordinated in a single percept.” (Eric R. Kandel, James H. Schwartz, and Thomas M. Jessell, Principles of Neural Science, 4th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2000), 496.) Some time ago, Semir Zeki showed that the processing of different properties such as motion, color, form, and depth occur in different areas, simultaneously, building up a perception with interacting layers of input along multiple pathways and processed in parallel and that “integration can be achieved only interactively.” (Eric R. Kandel, James H. Schwartz, and Thomas M. Jessell, Principles of Neural Science, 4th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2000), 505.) See Semir Zeki, A Vision of the Brain (Oxford: Blackwell, 1993). See also Antonio Damasio, Feeling and Knowing: Making Minds Conscious (New York: Pantheon Books, 2021) for the role of feeling and emotion in perception. Rudolf Arnheim, Art and Visual Perception (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1954) lays out the phenomena of visual perception.

(3) Eric R. Kandel, James H. Schwartz, and Thomas M. Jessell, Principles of Neural Science, 4th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2000), 493.

(4) The first chapter of Jonathan Fineberg, Modern Art at the Border of Mind and Brain, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2015).

(5) See Elizabeth Hutton Turner and Oliver Wick, editors, “The Correspondence of Alexander Calder and Joan Miró,” in Elizabeth Hutton Turner and Oliver Wick, Calder/Miró, exhibition catalogue (Washington, D.C.: The Phillips Collection, 2004), 258. “Calder and Miró conducted their correspondence in French and Spanish. Neither was a native French speaker. Miró’s first language was Catalan and he never learned English. They did not share a common tongue and their polyglot exchanges are rife with mistakes.”

(6) Alexander S. C. Rower, Emilio Fernández Miró, and Joan Punyet Miró, “Foreword,” in Elizabeth Hutton Turner, Calder Miro (Riehen/Basel: The Fondation Beyeler and Washington, D.C.: The Phillips Collection, 2004), 13.

(7) Luisa Calder, from a 1958 conversation related by George Staempfli and cited in Jean Lipman, Calder's Universe, edited by Ruth Wolfe (N.Y.: Viking Press and the Whitney Museum of American Art, 1976), 266.

(8) Alexander Calder and Jean Davidson, Calder: An Autobiography with Pictures (New York: Pantheon Books, Random House, 1966), 271.

(9) Nicholas Guppy, “Alexander Calder,” Atlantic Monthly (December 1964), cited in Albert Elsen, “Calder on Balance,” Alexander Calder: A Retrospective Exhibition, Museum of Contemporary Art, (Chicago: Museum of Contemporary Art, 1974), note 28, n.p.

(10) Elsen, “Calder on Balance,” op. cit., n.p.

(11) Margaret Calder Hayes, Three Alexander Calders: A Family Memoir (Vermont: Paul S. Eriksson, 1977), 14.

(12) Hayes, op. cit., 7-8.

(13) See Jonathan Fineberg, The Innocent Eye: Children’s Art and the Modern Artist (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997), in which I discussed the importance of childhood and child art as an opening into the most sophisticated level of the central concerns of many of the major masters of 20th century art.

(14) Hayes, op. cit., 18; Calder and Davidson, op. cit., 15.

(15) Calder and Davidson, op. cit., 54-5.

(16) Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1756), edited with introduction and notes by J. T. Boulton (Notre Dame, IN and London: University of Notre Dame press, 1968), 57: “The passion caused by the great and sublime in nature, when those causes operate most powerfully, is Astonishment; and astonishment is that state of the soul, in which all its motions are suspended, with some degree of horror. In this case the mind is so entirely filled with its objet, that it cannot entertain any other, nor by consequence reson on that object which employs it. Hence arises the great power of the sublime…”

(17) See Catherine Freedberg, The Spanish Pavilion at the Paris World’s Fair (New York and London: Garland, 1986), 504-505; and Alexander S. C. Rower, Alexander Calder 1898-1976 (Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1998), 137. I also want to thank my colleagues Jordana Mendelson and Rob Lubar for sharing with me their thoughts on the Pavilion.

(18) Michel Leiris, “Joan Miró”" Documents 5 (October 1929) 264-265.

(19) André Breton, Génèse et perspective artistique du surréalisme, 1941, reprinted in Le Surréalisme et la peinture (N.Y.: Brentano, 1945), 94; cited in Robert Goldwater, Primitivism in Modern Art, enlarged edition (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1986), 128.

(20) Anne Umland, “Miró the Assassin,” in Anne Umland, Joan Miró: Painting and Anti-Painting, 1927-1937 (N.Y.: Museum of Modern Art, 2008), 2-3.

(21) Joan Miró, in James Johnson Sweeney, “Joan Miró; Comment and Interview,” Partisan Review (New York: February 1948); in Margit Rowell, ed., Joan Miró: Selected Writings and Interviews (Boston: G. K. Hall, 1986), 212ff. For larger discussion of Miró and childhood see Jonathan Fineberg, “Miró’s Rhymes of Childhood,” in The Innocent Eye: Children’s Art and the Modern Artist (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1997), 150.

(22) Joan Miró, in: Dean Swanson, “The Artist’s Comments: Extracts from an Interview with Joan Miró (19 August 1970, St.-Paul-de-Vence),” Miró Sculptures (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 1971), n.p., also quoted in the webtext for this work at the Tate Gallery, London.

(23) Calder and Davidson, op. cit., 92.

(24) The first postcard pieces by Miró are the 1933 Drawing-Collage works. Calder’s reference might be to any of three Spanish Dancers (now in the Neumann collection, the Musée Nationale d’Art Moderne in Paris, and the Raina Sofia in Madrid). Thanks to Anne Umland of the Museum of Modern Art in New York for help sorting through this problem. For an examination of the first postcard pieces, see Jordana Mendelson, “Joan Miró’s Drawing-Collage, August 8, 1933: The ‘Intellectual Obscenities’ of Postcards,” Art Journal (Spring 2004), 24-37.

(25) Landscape Autumn (The Hare) and several other “summer landscapes” of 1926-7 by Miró were shown at Bernheim’s gallery in Paris in May 1928.

(26) Joan Miró, in “For a Big show in France, Calder ‘Oughs’ His Works,” New York Times (3 April, 1969); cited in Elizabeth Hutton Turner “Calder and Miró: A New Space for the Imagination,” in Elizabeth Hutton Turner and Oliver Wick, eds., Calder Miró (Washington, D.C.: The Phillips Collection, 2004), 29.

(27) Joan Miró, in Yvon Taillandier, “I Work Like A Gardener,” interview with Joan Miró, XXe Siècle, No. 1 (Paris, February 15, 1959), 4-6, 15; cited in Rowell, op. cit., 248.

(28) Joan Miró, in Dora Vallier, "Avec Miró," Cahiers d'Art, volume 33-35 (1960), 174; reprinted in Dora Vallier, L'Intérieur de l'Art (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1982), 144.

(29) Joan Miró, in Gaëton Picon, Joan Miró: Carnets catalans, volume 1 (Geneva: Albert Skira, 1976); cited in Werner Schmalenbach, "Drawings of the Late Years," in Joan Miró: A Retrospective (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1987), 51.

(30) Hayes, op. cit., 7.

(31) Joan Miró, “statement,” Minotaure (Paris), December 1933; in Margit Rowell, ed., Joan Miró: Selected Writings and Interviews (Boston: Twayne, 1986), 122.

(32) Sigmund Freud, “The Moses of Michelangelo,” (1914), in Totem and Taboo and Other Works, vol. XIII, The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, trans. James Strachey (London: The Hogarth Press and The Institute of Psycho-Analysis, 1955), 211.

(33) Roland Barthes, Sade, Fourier, Loyola (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989).

(34) J. J. Winckelmann, Geschichte der Kunst des Altertums (History of the Art of Antiquity), Dresden: 1764, 393; cited in Alex Potts, Flesh and the Ideal: Winckelmann and the Origins of Art History (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1994), 127.

(35) Max Kozloff, “Art,” The Nation (New York), 148, no.7 (February 10, 1964), 151.

(36) Charles Baudelaire, “The Salon of 1846,” Art in Paris: 1845-1862, Salons and Other Exhibitions, translated and edited by Jonathan Mayne (London: Phaidon Press, 1965), 94.

(37) Joan Miró, Letter to Roland Tual, Montroig, July 31, 1922, in Rowell, op. cit., 79.

(38) Sigmund Freud, “Creative Writers and Day-Dreaming,”(1908), The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, trans. James Strachey, vol. IX (London: The Hogarth Press and The Institute of Psycho-Analysis, 1959), 153.

(39) Ernst Kris, Psychoanalytic Explorations in Art (N.Y.: International Universities Press, 1952), 318.

(40) Samuel Weiss sums up the literature well in his review of Gudmund J. W. Smith and Ingegerd M. Carlsson, The Creative Process: A Functional Model Based on Empirical Studies from Early Childhood to Middle Age (Madison, CT: International Universities Press, Inc., 1990), in Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 63 (1994): 599. He also notes that Smith and Carlsson “even suggest that the sensitivity, coming close to projection, allows internal threats to be experienced as outside.”

(41) Joan Miró, Letter to Michel Leiris, Montroig, September 25, 1929, in Rowell, op. cit., 110.

(42) Ross Feld, “Philip Guston: an essay,” in Philip Guston, exhibition catalogue (New York: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and George Braziller, Inc., 1980), 29; also cited in Musa Mayer, Night Studio: A Memoir of Philip Guston by His Daughter (New York: Viking-Penguin Books, 1988), 182.

(43) Lipman, op. cit., 32.

(44) See, for example, Sigmund Freud, The Ego and the Id, (1923), The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, trans. James Strachey, vol. XIX (London: The Hogarth Press and The Institute of Psycho-Analysis, 1961), 26-7. Freud defines the ego as an integrating mechanism between inner drives and the demands of the outer world; it modifies, redirects, represses, and disguises aspects of the unconscious in order to navigate external reality successfully and at the same time quiet or satisfy inner urges to a tolerable level.

(45) D. W. Winnicott. “Ego Distortion in terms of the True and False Self,” The Maturational Processes and the Facilitating Environment: Studies in the Theory of Emotional Development (London: The Hogarth Press, 1965), 148-149.

(46) Robert Motherwell, “Painting As Existence: An Interview with David Sylvester,” 1962, in Robert Motherwell, Dore Ashton and Joan Banach, eds., The Writings of Robert Motherwell (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 205.

(47) Sigmund Freud, Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis (Part III), (1917), The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, trans. James Strachey, vol. XIX (London: The Hogarth Press and The Institute of Psycho-Analysis, 1963), 375.

(48) See Jacques Lacan, Les complexes familiaux dans la formation de l’individu: Essai d’analyse d’une fonction en psychologie (1938), (Paris: Navarin, 1984).

(49) Jacques Lipchitz, with H. H. Arnason, My Life in Sculpture (N.Y.: Documents of Twentieth Century Art, Viking Press, 1972), 195.

(50) Arnheim argued this point of view for half a century. Most recently in Rudolf Arnheim, “Beginning with the Child,” in Jonathan Fineberg, editor, Discovering Child Art: Essays on Childhood, Primitivism, and Modernism (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1998), 16. “The child meets the world mainly through the senses of touch and sight, and typically it soon responds by making images of what it perceives... The picture, far from being a mere imitation of the model, helps to clarify the structure of what is seen. It is an efficient means of orientation in a confusingly organized world.”

(51) Charles Baudelaire, "The Painter of Modern Life" (1863), in The Painter of Modern Life and Other Essays, translated and edited by Jonathan Mayne (London: Phaidon Press, 1964), 8; Charles Baudelaire, Oeuvres Complètes (Bruges: Gallimard, 1961), 1159.

(52) For an interesting discussion of this issue see Jonathan Lear, Love and Its Place in Nature (New Haven, Yale University Press, 1990).

(53) Willem de Kooning in Harold Rosenberg, “Interview with Willem de Kooning,” Art News, (September 1972); reprinted in Harold Rosenberg, Willem de Kooning, (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1973), 47.

(54) Willem de Kooning, “Content is a Glimpse,” excerpts from an interview with David Sylvester broadcast on the B.B.C., December 3, 1960; published as a transcript in Location, vol. I, no. 1 (Spring 1963); reprinted in Thomas B. Hess, Willem de Kooning, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, (Greenwich, CN: New York Graphic Society, 1968), 148.

(55) See Henry F. Smith “Analytic Listening and the Experience of Surprise,” International Journal of Psycho-Analysis v.76, part 1 (February 1995): 71. “Like Freud’s notion of the uncanny,” Smith observed, “behind most surprises that I have examined lie reminders of something almost known or once known and long forgotten, something that comes to life again.”

(56) “For man, no question whatever, is sicker, less secure, more changeable, more unfixed than any other animal,—he is the sick animal. And why so? Certainly he has also dared more, innovated more, defied more, challenged fate more than all other animals taken together,—he, the great experimenter, the unsatisfied and insatiate one, struggling with animal nature and the gods for final supremacy,—he, the still unconquered, the eternally futurous one who finds no rest from his own thronging power, so that his future like a spur inexorably rakes the flesh of every Now of his. How could it happen that such a courageous and rich animal should not also be of all sick animals the one more jeopardised, the one with the longest and deepest sickness? Man is satiated to surfeit, often enough; there are entire epidemics of this satiety (—for instance, about the year 1348, the time of the ‘dance of death’). But even this nausea, this weariness, this self-annoyance,—all this becomes so powerfully apparent in him that at once it turns into an additional fetter.” Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche, The Genealogy of Morals in: The Works of Friedrich Nietzsche, vol. X, ed. Alexander Tille, trans. William A. Hausemann (N.Y.: Macmillan, 1897), 166. See also Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche, Thus Spake Zarathustra: A Book for All and None, The Complete Works of Friedrich Nietzsche, vol. 11, ed. Oscar Levy, trans. Thomas Common (N.Y.: Macmillan, 1911), 260-61. If the psyche is too overwhelmed to be able to reorganize, somatization may be the result and somatization itself is linked with regression.

(57) William S. Burroughs, Naked Lunch (New York: 1959), v.

(58) Sigmund Freud, The Ego and the Id, in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Strachey trans., vol. XIX (London: The Hogarth Press and The Institute of Psycho-Analysis, 1961), 21: “It is possible for thought-processes to become conscious through a reversion to visual residues, ...[but]... the relations between the various elements of this subject-matter, which is what specially characterizes thoughts, cannot be given visual expression. Thinking in pictures is, therefore, only a very incomplete form of becoming conscious. In some way too, it stands nearer to unconscious processes than does thinking in words, and it is unquestionably older than the latter both ontogenetically and phylogenetically.”

(59) Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams, in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Strachey trans., vols. IV&V (London: The Hogarth Press and The Institute of Psycho-Analysis, 1961), 467-8, and elsewhere.

(60) Works of art have both the dialectic and the internal strife to which Heidegger alluded in his famous essay on “The Origin of the Work of Art.” Martin Heidegger, “The Origin of the Work of Art,” 1935-6 (revised 1950), in Poetry, Language, Thought, translated by Albert Hofstadter (New York: Harper and Row, 1975), 63-4.Martin Heidegger, “The Origin of the Work of Art,” 1935-6 (revised 1950), in Poetry, Language, Thought, translated by Albert Hofstadter (New York: Harper and Row, 1975), 63-4.

(61) Francis Bacon, October 1973, in Francis Bacon Interviewed by David Sylvester (N.Y.: Pantheon, 1975), 100.

(62) Denis Hollier, Against Architecture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1989), 31.

(63) See Sigmund Freud, “Formulations on the Two Principles of Mental Functioning,” (1911), The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, trans. James Strachey, vol. XII (London: The Hogarth Press and The Institute of Psycho-Analysis, 1961), 218-226.

(64) See, for example, Sigmund Freud, “New Introductory Lectures on Psycho-Analysis,” (1933 [1932]), The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, trans. James Strachey, vol. XXII (London: The Hogarth Press and The Institute of Psycho-Analysis, 1961), 96.

(65) See Lacan, op. cit., 33ff.

(66) Gerhard Richter, The Daily Practice of Painting (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1995), 35.

(67) See Joyce McDougall, The Many Faces of Eros: A Psychoanalytic Exploration of Human Sexuality (New York: W. W. Norton, 1995).

Adapted from Modern Art at the Border of Mind and Brain by Jonathan Fineberg by permission of the University of Nebraska Press. © 2015 Jonathan Fineberg.