YOU GOTTA WOO

This piece is part of a series that responds to the theme of the 2023 Cleveland Humanities Festival: “Wellness.”

What if I were to tell you I slow-danced with a boy?

And that the whole time we danced, I kept asking myself questions I didn’t have the answers to.

Questions like: What does it take to help a boy realize his body is safe? What does it take to help a boy realize his body is okay? That sleep, regardless of what is happening, is always possible if he allows himself to give in to his eyelids? If he allows his vision—like a slow-dance itself—to spin into the arms of a dark bedroom, into the sound of his father’s raspy voice?

But still, I ask, what if I were to tell you that I—a 31-year-old Black man in America—slow-danced with a boy? What would you make of me?

Well I did. I slow-danced with a boy but not like lovers would.

The house, the night I slow-danced with a boy, was full of people and on the outside covered with snow.

I slow-danced with a boy because I wanted him to fall asleep.

I slow-danced with a boy hoping that it would make me a good father.

I slow-danced with a boy because, at the time, it was the most romantic thing I could do.

///

The evening you refused to sleep, we were over a hundred miles away from our home in Cleveland. A Rust Belt city to which—because of you—your mother and I will forever be tethered.

But the evening you refused to sleep, we were tucked inside your grandparents’ home in Columbus. We were safe from an arctic blast sweeping across the city. We arrived in Columbus a day and a half earlier than planned because we wanted your first road trip to be a trip unbridled by the weather. We anticipated like lovers—your mother and I—the condition of the roads, the mood of the sky. How quickly visibility goes when driving down the long, empty stretch of I-71 South.

Everything, we said without saying, must be right.

We were new parents and two days out from your first Christmas. The evening you refused to sleep, we watched the news, sat around in our pajamas. Your older cousin was awestruck by your new, small life.

“Baby,” she said.

“Yes,” we affirmed.

“Baby?” she pointed.

“His name is August,” we said.

It went like that all day.

We anticipated the storm.

///

The song ends before I am ready for the song to end. I understand why.

The song ends before I am ready because the song is unfinished. The song remains unfinished. In its posthumous success, though, the unfinished version is the finished version. It’s hard to imagine Otis Redding going back to Memphis, after having written the remaining verse of “Dock of the Bay,” and stepping into the studio to pick up where he, his band members, and Steve Cropper left off. It’s hard to imagine a fourth verse sung in his subtle voice.

See, time has a way of making meaning, and then reshaping meaning.

The whistling at the end of the song has become the fourth verse.

I can’t imagine the song ending any other way.

///

///

During our stay at your grandparents’ house, we learned that you liked being sung to while being held and put to sleep. Prior to this discovery, you cried uncontrollably and all we could do was pass you from one adult to another, in an attempt to help soothe you, to help bring you to a level of calm that allowed for sleep to come on easily.

After rounds of being passed between mom, dad, and family members, you ended up in your grandfather’s arms. In the beginning, while in your grandfather’s arms, you wailed. But then your screaming waned and your breathing, like an airplane’s engine going idle upon arrival at the gate, slowed down. Your breathing became heavy. Labored. Metronome like.

Throughout the living room, your grandfather sang to you.

The girl from Ipanema goes walking…

With you cradled in his arms, he slid around the carpeted living room floor but not like a ballroom dancer would.

Like that, you were out.

///

It wasn’t a bad dream you had woken up from. But the sleep you could not soothe yourself into. But like Megan writes about in her essay, there is a “holiness in being a child’s midnight solace.” It isn’t the three a.m. feeding, but the heavy-bodied, red-eyed dance I do in the night with you after the feeding. After you have unlatched from mom’s nipple and fidget back and forth in my arms. I become the fog billowing around the bodies of New England lighthouses.

///

In my notebook, I made a slight observation. A few weeks later, I would tweet my observation, feeling a slight discomfort. There was something about naming babies, sleep, and romance in the same sentence that felt off. That felt perverse. But then I remembered: this observation is my experience of putting an infant to sleep, of me (a father) putting you (a son) to sleep. But then it clicked, not like a seatbelt but like a tongue against the roof of the mouth, as I held you in my arms and walked a thousand circles in the dark of the room we shared at your grandparents’ house. Under my breath I sang Otis Redding’s “Dock of the Bay” to you. I slid around the carpeted bedroom floor but not like a ballroom dancer would.

The song is timeless in its nothingness. The song, once it passes over our heads, once it comes down safely out of the sky and it lands, you recognize is a song about presence, stillness, of sitting and doing nothing. We are made to witness the natural movements of the sun and moon, the transient nature of ships on the water. We are made to look inward, to ask ourselves—amongst the sun and the moon and the ships off to port within us—what is the meaning of it all? It: an American life. It: a father holding his newborn son against his chest, slow-dancing circles in the dark.

By the time I got to the end of the song, to that beautifully tuned whistle, you were out.

///

///

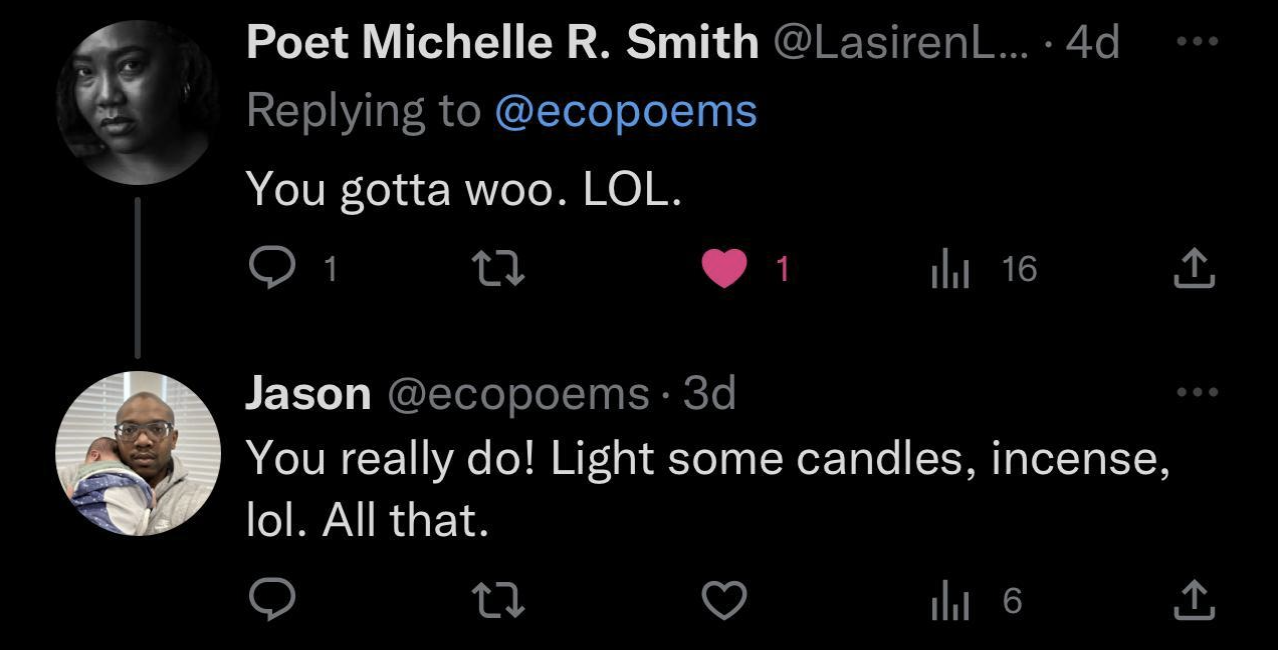

Michelle is right. And made me feel safe in my observation. Putting a baby to sleep is an act of romance. From beginning to end it is a dance. An act of seduction. The lighting of the room, the temperature of the room, the sound level—all must be perfect. You do gotta woo. You gotta light some candles, incense. All that. You gotta hold the baby close at three a.m. and sing to it until it falls asleep; slow-dance with it until you fall in love.