Against Nature: On Laboria Cuboniks' "Xenofeminist Manifesto"

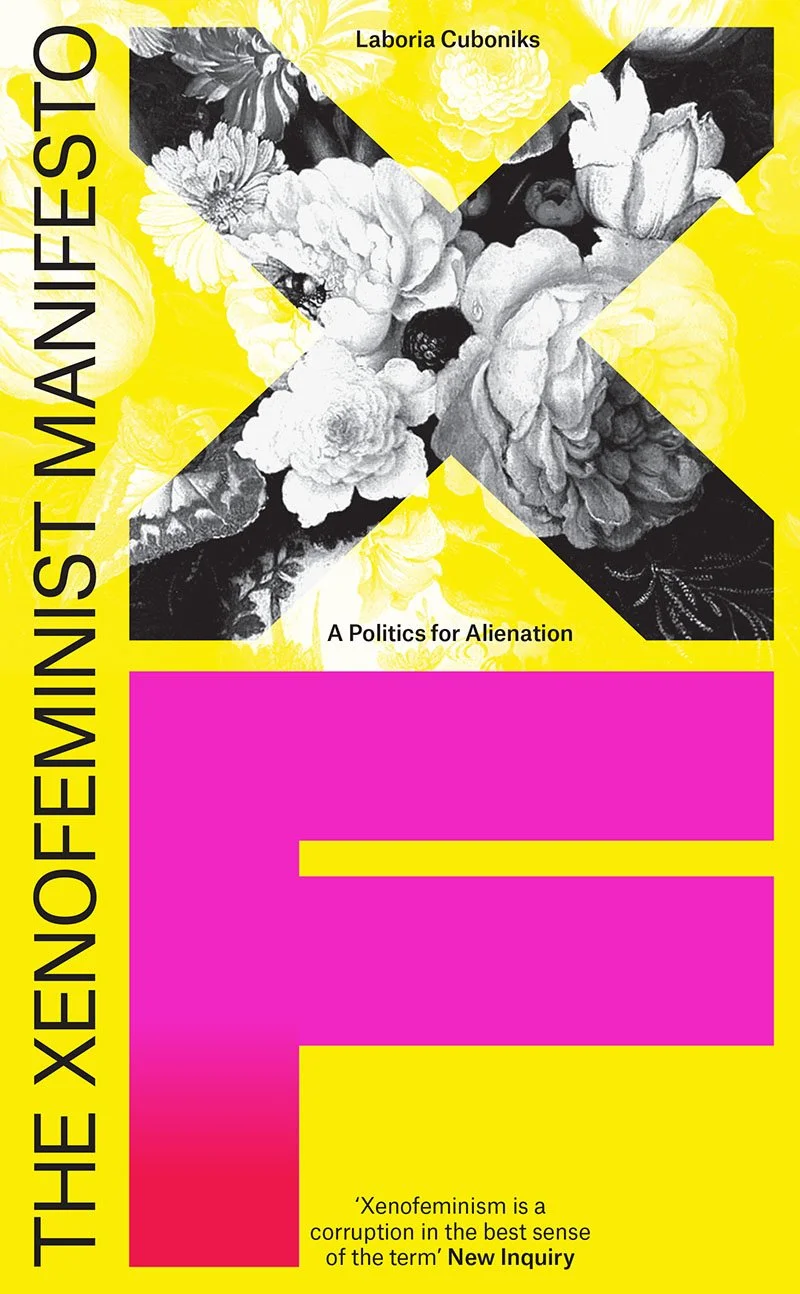

Laboria Cuboniks | Xenofeminist Manifesto | Verso Books | October 2, 2018 | 96 Pages

Xenofeminist Manifesto: A Politics for Alienation is authored by the anonymous feminist collective Laboria Cuboniks. LC is comprised of six women who, in their manifesto, attempt to “denaturalize” the disciplines of science, technology, and ultimately, rationalism, from the grip of patriarchal power. Described as a “pocket colour manifesto for a new futuristic feminism,” the book is divided into seven parts: Zero, Interrupt, Trap, Parity, Adjust, Carry, Overflow. Much like the technological horizon that the book points toward, the language is distinct from the flowery excess of other manifestos--it is succinct, determined, and streamlined for mobility. Each proclamation acts as a direct conduit to the motherboard.

Certainly feminism’s relationship to nature has been both extensive and fraught--at once a rejection of ‘biologically ordained’ subservience and an embrace of the organic, the goddess Mother loosed and barefoot. The “natural” is as much the enemy to a cooperative, feminist, anti-racist, and many-gendered future as it is at the foundation of movements most aligned with it (environmentalism, holistic medicine, the urban garden.) We wish to say that the two sexes are false, but the rivers are fact. The xenofeminist tagline is, “If nature is unjust; change nature!” Does this mean essentialism is the ally of nature and thus, nature is the enemy of our most liberated future? Is the “alienation” espoused by technology in fact our most intrepid vehicle for progress?

Xenofeminism is the antidote to the ills of naturalism, machinated in the sense that it is built and serviced. Naturalism is likened to theology--a mythos perpetuated as fact, designed to maintain power in the hands of those who wield it. In other words: the “biological given” of the objectivity of male and female is a cosmic faith in the invariability of oppression. However, LC does not claim that technology is inherently progressive. They understand that, like all things, it is in the image of its creators. Currently, those creators are men--the gender disparity in STEM is enormous, and gender inequality “characterizes the fields in which our technologies are conceived, built, and legislated for.” If nature has been the ally to essentialism, then science and technology have been the ally to rationalism--that system which has put the gavel in the hands of old white dudes to decree our impulses toward empathy, justice, and love as the illogics of hysteric beings. Our technologies, much like our systems of what constitutes the rational, are engines made to fuel the locomotive of male power.

LC responds to this with a front-and-center sucker punch: “Rationalism itself must be a feminism.” Right to the girl-gut. We have said this: quietly with academic integrity, and yelled across the table, at the fronts of men and to their backs, with many more words in much sloppier ways: that the heart is the matter. My main qualm with the vision of xenofeminism is this: its merely cursory mention of family and caregiving. It addresses the domestic sphere only in order to vaguely assert that it must not be exempt from the transformative power of computation, with little to no explication of how or what this would look like. We know this to be the aggressive downfall of organizational systems, of economics that “assumes children come from cabbage patches” in the resounding words of Shirley P. Burggraf (author of The Feminine Economy & Economic Man). Of course in any vision of a more just world, we would like to believe our private worlds would be as lovingly radicalized as our public one, but this requires at the very least an addendum of the same length to paint a compelling portrait of and manual toward.

At this point, my question was, where is this--the mess of self, the gore of labor--in the hydra-gendered alien future of glass and chrome? Perhaps that’s just what we imagine the hyper-futuristic to be, as crafted by the masculine imagination. What would a feminist techno-future look like?

Digital frameworks and coded systems of dancing algorithms scaffold not only our current existence, but the future of it. If technoscientific innovation is spearheaded by men, then so too will they determine the destiny of our world. Until technology is linked to a theoretical and political framework that works to enfranchise women and non-binary/queer identities, the world it subsequently constructs will not be one made for us. This argument is not unlike the prominent social and philosophical theory that our world is constructed by the language we use. That is, by revolutionizing our vocabulary in the direction of abolitionist language, we manifest its reality--by the same token, antiquated vocabularies from oppressive eras do a violence unto the project of liberation. Xenofeminism applies this to the scope of technology. After all, code is also language.

Still, technology isn’t the vision: it’s the tool. LC reminds us that so many anti-capitalist projects have died in the water because of their failure to use the globalizing technologies available to them, out of the fear that universals equal absolutes--the cardinal sin of progressivism. This reduces these bids for revolution to “fragmented insurrections” in “fixed localities.” In other words, we have wrongly equated the ills of capitalism with the ills of globalization. What could we accomplish past the singular item of anarcho-communes on the Left’s list of ideas? “Our digital age requires a feminism at ease with computation.” To dismiss the singular greatest revolution to the way we communicate (“Reality is crosshatched with the unrelenting, simultaneous execution of millias of communication protocols”) because of its current predicament in the hands of Silicon Valley dude-bros, might be one of the most regretful symptoms of “the malady of melancholia endemic to the Left.”

If nothing else, the Xenofeminist Manifesto is a vision of feminism that intends to avoid throwing away the prodigal baby with the bath water. LC writes, “We should not hesitate to learn from our adversaries or the successes and failures of history.” As if to directly apply this tenet, in “Adjust,” they rewind with the following: “to say that nothing is sacred is to say that nothing is supernatural.” We arrive at the understanding that to reject nature is at once to sanctify it as real, as an “unflinching ontological” reality, when nature is defined by xenofeminism as “the unbounded arena of science--it is all that there is.” Our rejection of nature is as natural as anything. Our impulse to create, to better, to unify, to imagine, is as natural as a woman and a man; as a many-gendered android. The feminist techno-future can manifest, pixel by pixel, leaf by leaf, if we so empower it.