Remembering Emmett Till: On Elliot J. Gorn's "Let The People See"

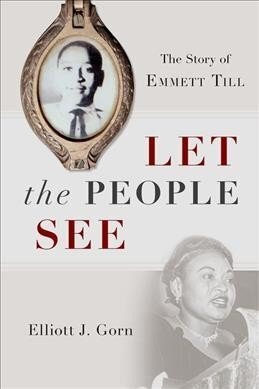

Elliot J. Gorn | Let The People See: The Story of Emmett Till | Oxford University Press 2018 | 392 Pages

Around two in the morning on August 24, 1955, Roy Bryant and his half-brother, J.W. Milam, pulled up to the home of Mose Wright, a part-time preacher and full-time cotton farmer in the Mississippi Delta. Holding a pistol in one hand and a flashlight in the other, Milam demanded that “Preacher” Wright, a Black man, turn over his grandnephew, Emmett Till, for questioning. Bryant and Milam wanted to find out whether Emmett was the boy who allegedly wolf-whistled, insulted, or perhaps touched Bryant’s wife, who worked behind the counter at Bryant’s grocery store in the little town of Money. Wright, suggesting that Emmett did not yet know the ways of the South, explained that the boy had arrived from Chicago only a week before. Wright feared that if Bryant and Milam took the boy away, Emmett would never be seen again. Wright was so alarmed that he said Bryant and Milam could give Emmett a beating on the premises. Wright’s wife offered them money. Both offers were refused. Before taking Emmett away, Milam made it clear that Wright would be killed if he told anyone about what had transpired that night.

Three days later, the bloated body of Emmett Till was found by two boys fishing in the Tallahatchie River. There was a gunshot wound to the head, and while Emmett’s face was bludgeoned almost beyond recognition, his body was identified by a ring bearing his father’s initials. Bryant and Milam were arrested and charged with kidnapping and murder. At the trial, Mose Wright, risking his life by testifying against white men in Mississippi, identified Bryant and Milam as having kidnapped Emmett. The evidence was damning, and the judge and prosecutor more than competent, but when Tallahatchie County Sheriff Clarence Strider denied that he had identified the corpse as Emmett Till—he had earlier signed a death certificate to that effect—then the all-white jury, later citing “reasonable doubt,” acquitted Bryant and Milam. The rumor then conveniently circulated that Emmett was alive and that the corpse was someone else. When the body arrived in Chicago, Emmett’s mother, overcome by grief and rage, demanded that the casket remain open so the world could view the grotesque face of her tortured son. Thus, the title of Elliot Gorn’s new book, Let The People See: The Story of Emmett Till.

The Emmett Till murder triggered nationwide and international protests. Mamie Till Bradley, Emmett’s mother, undertook an impassioned and successful cross-country speaking tour on behalf of the NAACP to demand justice for her son. But after a while, it seemed that Emmett Till, like the 3400 other Black men who had been lynched or murdered with community acquiescence, would also be forgotten. Instead, there has been such an outpouring of scholarly and popular studies, film and TV documentaries that Emmett Till is far better known now than at any time since his murder. Why then another book?

Gorn does not claim to have uncovered much that is new but marshals sixty years of passionate, outraged and, articulate journalism and research into an eminently useful, clear, and detailed account of the trial and its aftermath. The book should appeal both to the general reader and to those engaged in the newly emerging field of memorialization, which seeks to explain why a given culture may forget the fallen or perhaps select an individual who not only will be remembered but also sanctified.

By carefully editing and quoting from the trial record, Gorn draws readers into this terrible tale. His book may not be To Kill A Mockingbird (possibly inspired by the Till trial) but Let The People See is gripping enough, and, unlike the famous novel, this story is true.

Although it was the fond hope of Mamie Till Bradley that her son not be forgotten, she would probably have been astonished at the degree to which he has been enshrined in the history of the civil rights movement. According to Gorn, when it appeared that Emmett Till might disappear from the pages of history, the Black community kept his story alive. The image of that battered face—shown in African American magazines but not the mainstream media—proved so indelible that there was no way, said Rosa Parks, that she was going to the back of the bus. In his speeches, Martin Luther King referenced the “crying voice of Emmett Till.” And when, at the time of the murder, young John Lewis realized that he too could have been “beaten, tortured, dead at the bottom of a river,” he committed himself at age 15 to the struggle.

While the martyrdom of Emmett Till energized the civil rights movement, few anticipated that the day would come when the new National Museum of African American would set up the Emmett Till Memorial room to display the coffin where the battered body once reposed. Even more remarkable, however, has been the willingness of the Delta to memorialize Emmett, reconstructing the Sumner County Courthouse, setting up an Emmett Till interpretative center, erecting historic signposts at the Tallahatchie River, the Bryant grocery store, and other key points, and issuing a formal apology recognizing “a terrible miscarriage of justice.” Travelers enjoying historic tourism will appreciate the painful irony that U.S, Highway 49 E, the “Emmett Till Memorial Parkway,” intersects with the “Clarence Strider Memorial Parkway” in Webb, the birthplace of Emmett’s mother.

What is going on here? The Mississippi Delta has not yet been transformed into a peaceful post-racial society. The signpost at the Tallahatchie was so riddled by gunfire that it had to be replaced with one that was bulletproof. Assertive Black men might steer clear of this place, but by the same token, they might steer clear of many other places north and south. Has the signposting, courthouse preservation, and public apology been undertaken to promote tourism? That may be true, but it also may be unfair. Decency may be lurking here, too. In any event, when we vow to “never forget,” then we also run the risk of turning slave marts and concentration camps into theme parks. But when the alternative is forgetting, that may have to do.