Recursive Anamnesis: On Emily Skaja's "Brute"

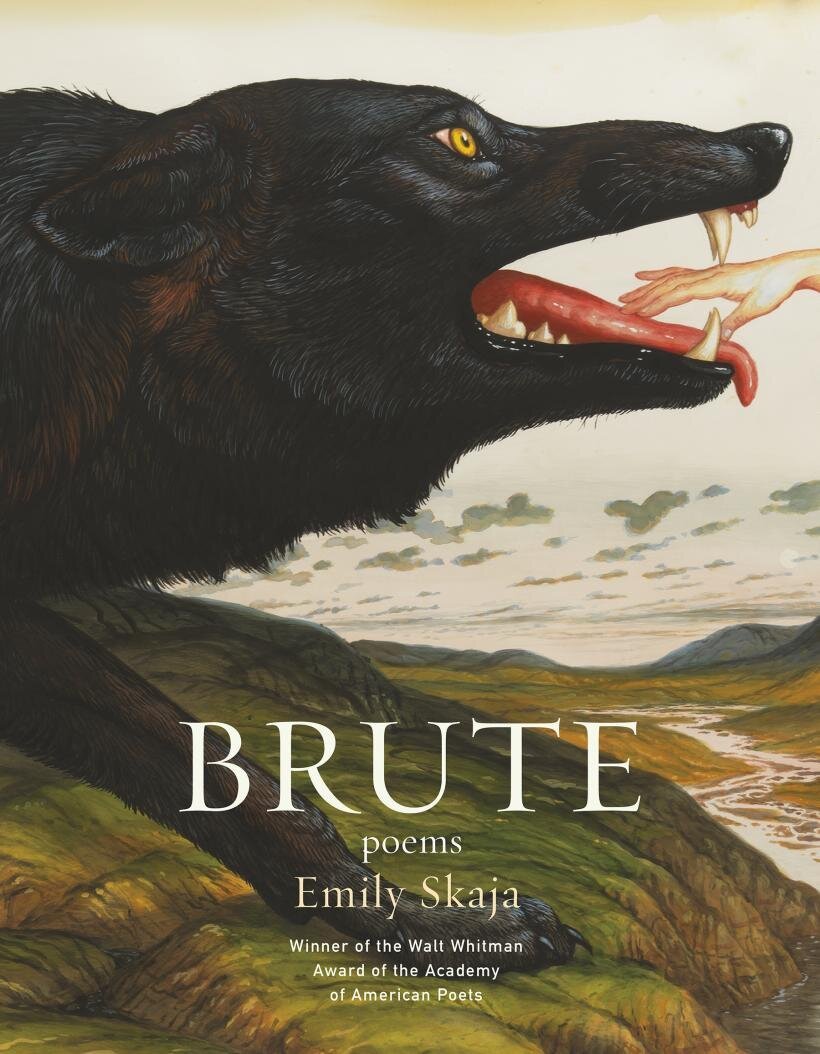

Emily Skaja | Brute | Graywolf | 2019 | 72 Pages

What made Sylvia Plath so appealing to readers in the early 1960s was her breakthrough style of confessional poetry. Pushing through a canon that at that point was intent on rigidity in verse and topic, she was a blunt realist who incorporated herself into her work, diminishing the distance between “I” and speaker. Each poem was a window into the strange world-making that occupied her time. Each poem was in the same way a window into her life. Plath addressed her subjects with an intense candor, some of her themes being depression, womanhood, and grief (though it shouldn’t be overlooked that Plath wrote on a host of other topics—most frequently forgotten are her series of landscape poems from 1961). Anthologized in 1970’s Sisterhood is Powerful, her poem “the jailor,” confronts the realities of leaving an abusive partner:

“I wish him dead or away.

That, it seems, is the impossibility.

That being free. What would the dark

Do without fevers to eat?

What would the light

Do without eyes to knife, what would he

Do, do, do without me?”

It is in the space carved out by Plath’s poems that Brute by Emily Skaja enters, her voice echoing among the chamber inhabited by poets like Sylvia Plath and Anne Carson, whose quotes serve as epigraphs at certain points in the collection. The book itself takes its name from a line in Sylvia’s poem “Daddy.” and is the winner of the Walt Whitman Award of the Academy of American Poets, being Skaja’s debut collection, released from Graywolf Press. Of the collection, Joy Harjo, this year’s judge of the award, says “Brute, through a collection of singular poems, is essentially one long, elegiac howl for the end of a relationship. It never lets up—this living—even when the world as we knew it is crushed. So what do we do with the brokenness? We document it, as Emily Skaja has done in Brute. We sing of the brokenness as we emerge from it. We sing the holy objects, the white moths that fly from out mouths, and we stand with the new, we earth that has been created with our terrible songs.”

Growing up in a house between two cemeteries seems an apt beginning for a poet. Emily Skaja says herself in an interview, “When I write, I feel haunted by the eerie isolation of that landscape, and those are the images that tend to creep into my poems. I was also trained as a poet to be a collector of strange images, and there is nothing like the natural world for strangeness.” Brute is itself a chamber inhabited by strangeness doled out into manageable doses, taking the shape of four sections in the book, corresponding loosely to loss, grief, anger, and strength. The eerie landscape creeps into the poems along with recurring images of birds and flight. The conceit being flight as a means of trapping and escaping simultaneously.

All throughout the collection Skaja confronts dichotomies head on, through the lens of leaving an abusive partner—beginning at what do I do with all this grief and ending with the strength to proceed into the waters of the next stage-of-life’s perhaps. She interrogates the enduring threat of violence against women, both from direct abuse and self-inflicted as a result of the abuse—intent on examining each side of the coin (THE BRUTE/BRUTE HEART): “The facts are: I drove all night through the mountains / to get away from him / I cut up my credit cards to prove I would not leave him / I woke up in the hospital” (DEAR KATIE): “I was trying to starve myself out of a feeling.”

This is the great strength of the collection, the forethought and meandering scope that examines every potential vantage-point of the situation. Emily does this both by re-engaging the past and through surrealism mixed with powerful imagery. The narrative is disjointed and takes place in recurrent cycles, often times revisiting the same event or emotion. Yet, Brute is intent on breaking the silence and cycle of abuse. There is a careful attention paid to not only individual sounds and their overlap within poems but also which characters in the poems are speaking. At the collection’s onset the prominent vocal entrances in the poems are the partner saying “I didn’t always / love you” (IN DEFEAT I WAS PERFECT) or sounds associated with violence (like the drunk hunters in ELEGY WITH A SHIT BROWN RIVER RUNNING THROUGH IT). Other voices enter Brute’s procession—the Angel in GIRL SAINTS and characters entering in order to confer strength upon the speaker. As the poems progress the speaker begins to gain a more prominent voice, vocalizing more often and confidently (MARCH IS MARCH):

“& I say You can’t keep doing this—

& I say What am I supposed to do—

& I say You don’t understand

I need to leave you EVERY DAY I need to leave.”

This collection exists in conversation with recent titles like Indictus by Natalie Eilbert, another forceful book confronting the realities of trauma and violence. Within it, Eilbert demolishes narrative and exposes its limitations in both form and content, featuring a speaker whose memory and language (the tools necessary for reconstruction of the past) are compromised in response to the trauma. Taking a different approach to the same topic, Brute embraces the limitations of narrative in response to trauma—becoming a portrait completed in layers, each successive one bringing the image into clarity. Brute becomes a recreation narrative, with each new cycle re-manifesting the same characters in different iterations, slowly growing towards health. The collection’s final poem is addressed to Eurydice, who remained in the Underworld despite Orpheus’ attempt to retrieve her—he fatefully looked back while leading her onward and she was forced to return. In the poem the speaker offers solidarity in doomed love, and strength seeking to help Eurydice find agency—doing for another what was done for her by previous characters in the collection, showing that community and support are necessary to beginning a new cycle apart from violence.

This review is part of the CRB x Barnhouse Series, which was created in partnership with Cleveland press and literary collective Barnhouse in order to better highlight recent poetry releases. Learn more about Barnhouse here.