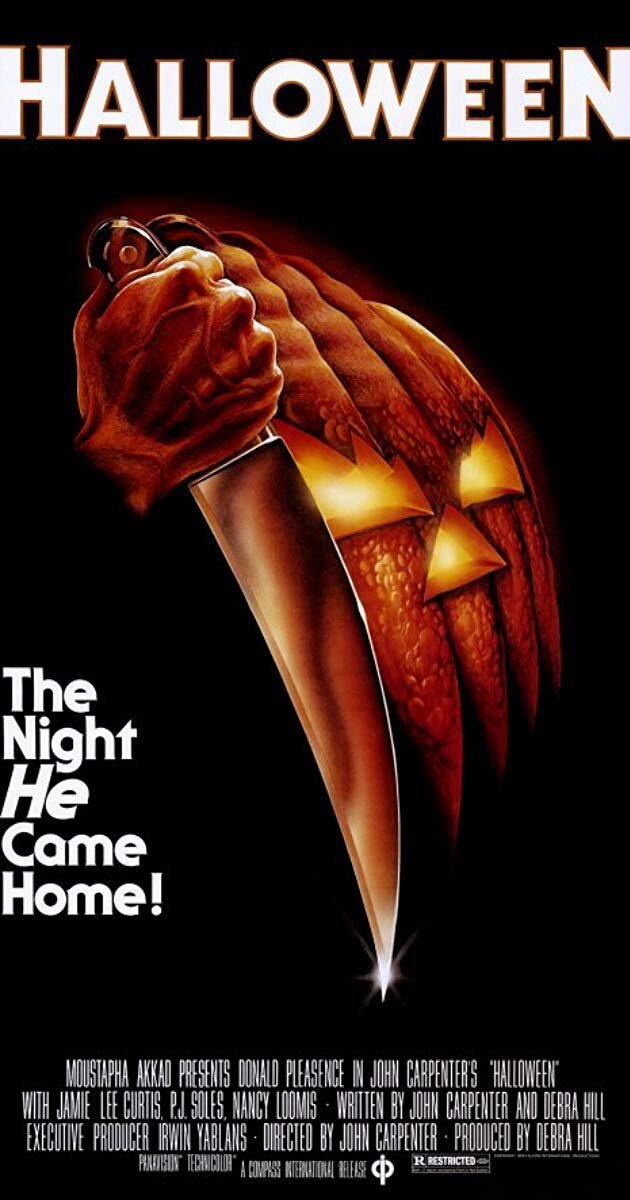

Death and Decay in the Suburban Midwest: On John Carpenter's "Halloween"

John Carpenter | Halloween | 1978

There is little about John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978) that isn’t iconic, or that hasn’t been copied and done in homage several times over, from Michael Myers’ uncanny mask (which careful viewers may recognize as a bleached Captain Kirk) to the carved pumpkins that flicker over the movie’s opening credits. This is perhaps most true of Halloween’s setting, the quiet, fictional suburb of Haddonfield, Illinois. The town’s name is the very first shot of the film, closely followed by establishing shots of the Myers family home, which both in its structure and residents reflects the ideal American family. Of course, any audience member, suburbanite or not, can understand that this peaceful beginning, complete with the sounds of children trick or treating, is about to be undercut, and so it is when a six year old Michael Myers blankly picks up a kitchen knife and proceeds to stab his older sister to death on Halloween night. Yet there is more to the suburban setting of Haddonfield than a trick of expectations, just as there is more to the silent Michael Myers than the “pure evil” that he ostensibly embodies. Indeed, it may be, as I suggest, that in the interplay between Michael and the Midwestern Haddonfield, we can better understand exactly what “lies beneath,” in the words of Halloween co-writer Debra Hill, our eerie discomfort with the American landscape, signified in horror film and literature by the suburban Midwest.

Essentially, why has Halloween’s preoccupation with the suburbs persisted? And how can the figure of Michael Myers possibly tell us anything about the common sense that Halloween is based on? He doesn’t even talk! Let’s begin with the suburbs themselves. From the Ohio anytown of the A Nightmare on Elm Street series (“every town has an Elm Street!”) to the reactionary Minnesotan zombies in Breck Eisner’s The Crazies (2010), there seems to be a clear recognition on the part of audiences and filmmakers that the suburbs are a site of unusual malevolence, and Halloween is ground zero for modern horror’s imagery of suburban life. However, while the above mentioned idea of horror “lying beneath” the suburbs is central to Halloween’s story, it also predates it. Horror fans will need no reminder, for example, of the genre’s long-running fascination with the fallout of white extermination of Native American people. Indeed, horror is one of the few popular genres where the history and presence of Native societies is consistently referenced, albeit often crudely, from The Shining’s thematization of Indigenous presence/absence, to IT: Chapter 2’s fictional Shokopiwah tribe, who serve primarily as a Macguffin. The link between historical violence by white settlers cannot be understated in explaining white suburban anxieties about unknown vengeful forces, such as those at play in Halloween.

Neither can the more recent history of racist redlining in America’s cities be ignored, especially in the North and Midwest. Indeed, Halloween and its horror progeny do not shy away from representing suburbia’s manufactured whiteness, and using it as a point of tension. Debra Hill indirectly alludes to this history in interviews, noting that “What’s so interesting to me about horror movies is they take place in small towns where they don’t have a huge police force. [Laughs.]” This point about policing is crucial because it points to an explanation for the Haddonfield police’s utter inability to stop Myers. Police departments large and small exist to define white space and white safety, under the assumption that small police forces can handle any conflict that racial and class homogeneity does not quash. Yet the root of Michael Myers’ power over Haddonfield is simple enough that it fits in the movie’s infamous tagline: “The night HE came home!” It is the twist of the knife, so to speak, of Halloween’s premise: Michael Myers is not an “outsider,” but an indisputable product of Haddonfield and its familial and social order, and thus his invasion of the suburb is simply a return.

Michael Myers’ capacity for destruction, much like the deindustrialization and opioid epidemics that would soon sweep through much of the suburban Midwest, is exacerbated by the atomizing structure of suburban neighborhoods. The importance of the suburban landscape to his bloody success is best demonstrated near the end of Carpenter and Hill’s film, when protagonist Laurie Strode encounters Myers at her friend’s house, and runs out into the street screaming for help, going so far as to bang on neighbors’ doors pleading, before running back to the house where she was babysitting, barely escaping Myers again in the process. In this moment, the isolating construction of the surrounding houses nearly dooms Laurie, as she bangs on a front door, watching helplessly as a figure walks up to a window, and proceeds to turn off their porch lights while she screams, “can’t you hear me? Oh God!”. Haddonfield exhibits the extreme ability of suburban construction to center the nuclear family and the fortress-like home over any sort of community based on interreliance, as its residents turn a blind eye to the brutal deaths of their neighbors.

In truth, there is perhaps little that distinguishes the American project in the Midwest from its aim in New England, California or the South. However, given the directory of cultural shorthand employed in film, it is hard to ignore the critical importance of setting so many stories of death and decay in America’s so-called heartland. And while Michael Myers can embody much of this fear of history, Halloween’s ending clarifies the dynamic between the silent killer and his hometown. Michael disappears after being shot, but mere moments after, his distorted breathing is heard over shots that zoom out from the inside of Laurie’s house to its façade, reminding us that Haddonfield’s stairways, living rooms and front porches are where Myers originated, and as long as they stand, he’ll always have someplace to come home to.