My First and Only Doll

Beuna Coburn Carlson | Farm Girl: A Wisconsin Memoir | University of Wisconsin Press | June 2020 | 232 Pages

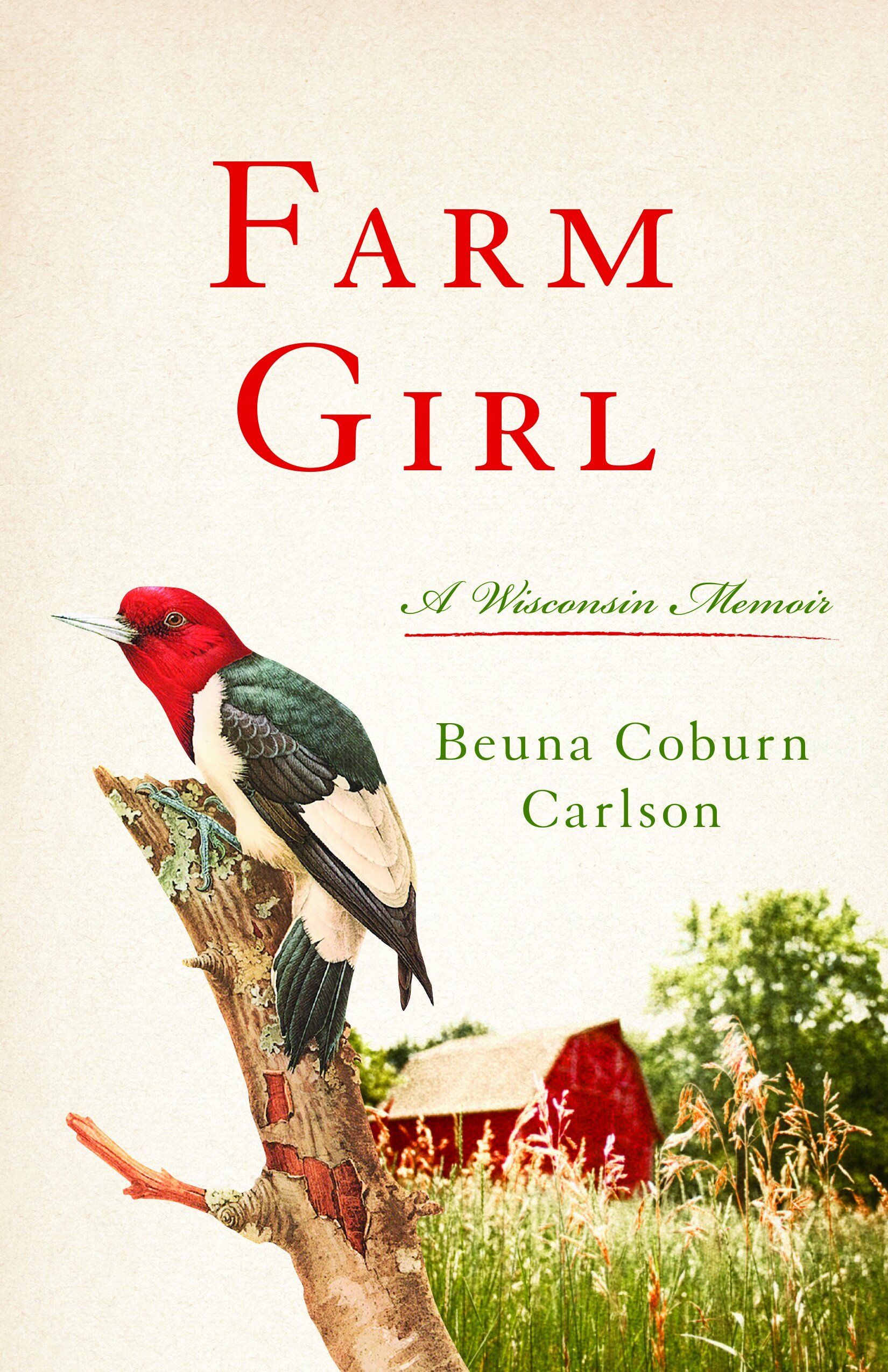

Beuna “Bunny” Coburn Carlson’s new memoir, Farm Girl, is a full and beautiful portrait of rural life in western Wisconsin. Set against the straining economic hardships of the Great Depression, summer heat, and crop failure, Carlson’s book chronicles the everyday rhythms of small-town life in extraordinary times.

Yet Farm Girl is about so much more than any single community or family story and its trials and triumphs in the early twentieth century. Carlson’s memoir is most valuable for its descriptions of how the social settings of her childhood adapted to and persisted through sweeping economic, technological, and cultural change. In countless vignettes, ranging from “The Slippery Elm Tre” to “The Dry Years,” which structure the book as miniature chapters, Carlson writes with a confidence and candor that recreates the circumstances of her childhood. In this excerpt of the story “My First and Only Doll,” the Clevland Review of Books is pleased to offer readers one such rendering of a farm girl’s youth in Wisconsin.

—Jacob Bruggeman

In the days before immunizations for various childhood diseases were mandated, most children experienced chicken pox, red measles, mumps, German measles, whooping cough, and, less often but regarded as more serious, scarlet fever. I believe my sister, brothers, and I had all of them except scarlet fever. The story circulated that one of my cousins had scarlet fever, and when he recovered he had curly hair. I, with my impossibly straight, strawlike hair thought that was not a bad bargain.

In 1902 the State of Massachusetts started a program of vaccinating schoolchildren for smallpox. Other states quickly followed. The disease was eradicated in the United States, and the last routine vaccinations were given in 1972, according to the New York State Department of Health.

I have reason to remember vividly the day the vaccinations were given at the public school in Plum City. Parents were waiting in the hallway with the children for their turns or comforting those who had already had the vaccine. I remember well that my mother was there to help with frightened children. She had no way to guess what was in store for her—or for me—that day.

As a little first grader, I, with my classmates, was learning a poem. Between attempts to recite the lines, I cried out in pain again and again. I still remember every word of the poem but not much about the next hours.

Dr. Anderson and his nurse were there to monitor the vaccination procedure. They or someone else finally realized that I was not just afraid of getting vaccinated, but in serious trouble. I was rushed to the hospital in Red Wing, Minnesota—if driving thirty miles over country roads in a 1928 Chevrolet can be called “rushed.”

I remember someone putting a mask over my face and telling me to blow up the big balloon. The memory of the smell of the ether as I obeyed and drew deep breaths has never left me. After two weeks in the hospital recovering from surgery for a serious abdominal problem, I returned home with a huge scar on my belly, a beautiful book signed by head nurse Miss Martin and the other nurses, and, from my classmates, a doll.

The book was round, made in the shape of a globe, with latitude and longitude lines on the cover. Inside were stories of two young adventurers as they traveled and learned about children in other parts of the world. I loved the book. I was not yet a good enough reader to decipher all the words, but I heard them many times as Mother read and reread about their adventures. My favorite of all the places they visited was the sub-arctic Baffin Island. Probably because I had experienced Wisconsin winters, I could relate to the children there. The Belgian Congo was of no interest to me.

If today’s focus on early childhood education is as effective as the experiences that shaped the person I became, every dollar invested should pay substantial dividends. My early exposure to music, art, poetry, and literature at school and at home, while basic and very limited, hinted at what was beyond the horizon. Dad’s love of Robert Burns and his poetry inspired me to travel to Scotland. Mother’s books by Longfellow and Hawthorne led me to New England to see the Great Stone Face of Hawthorne’s story and to visit the home of Longfellow, who had become a great favorite of mine.

The first and the only doll I ever had was a gift from my classmates while I was in the hospital. She was about eighteen inches tall with a ceramic head and hands, and a cloth body, and she was treasured beyond words. She now is loved by great-granddaughters as she sits in her own little highchair awaiting their visits. At some time during her long life, a mouse found her toes to be attractive and nibbled holes in her stockings, repaired at once by my mother. No other restoration to her ceramic hair or her tiny hands was allowed. She never had a name. She was simply My Big Doll.

Even in those hard times, people were willing to share what little they had. The children at school brought their meager contributions to buy the doll for me. I feel sure the teachers augmented those pennies and nickels and dimes from their own limited resources. So many decades later the fruit of their generosity brings joy to little girls as they hear the story of My Big Doll.

From Farm Girl by Beuna Coburn Carlson. Reprinted by permission of the University of Wisconsin Press. © 2020 by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System. All rights reserved.