The Blurred Man: On David Shields' "The Very Last Interview"

David Shields | The Very Last Interview | New York Review Books | 2022 | 164 Pages

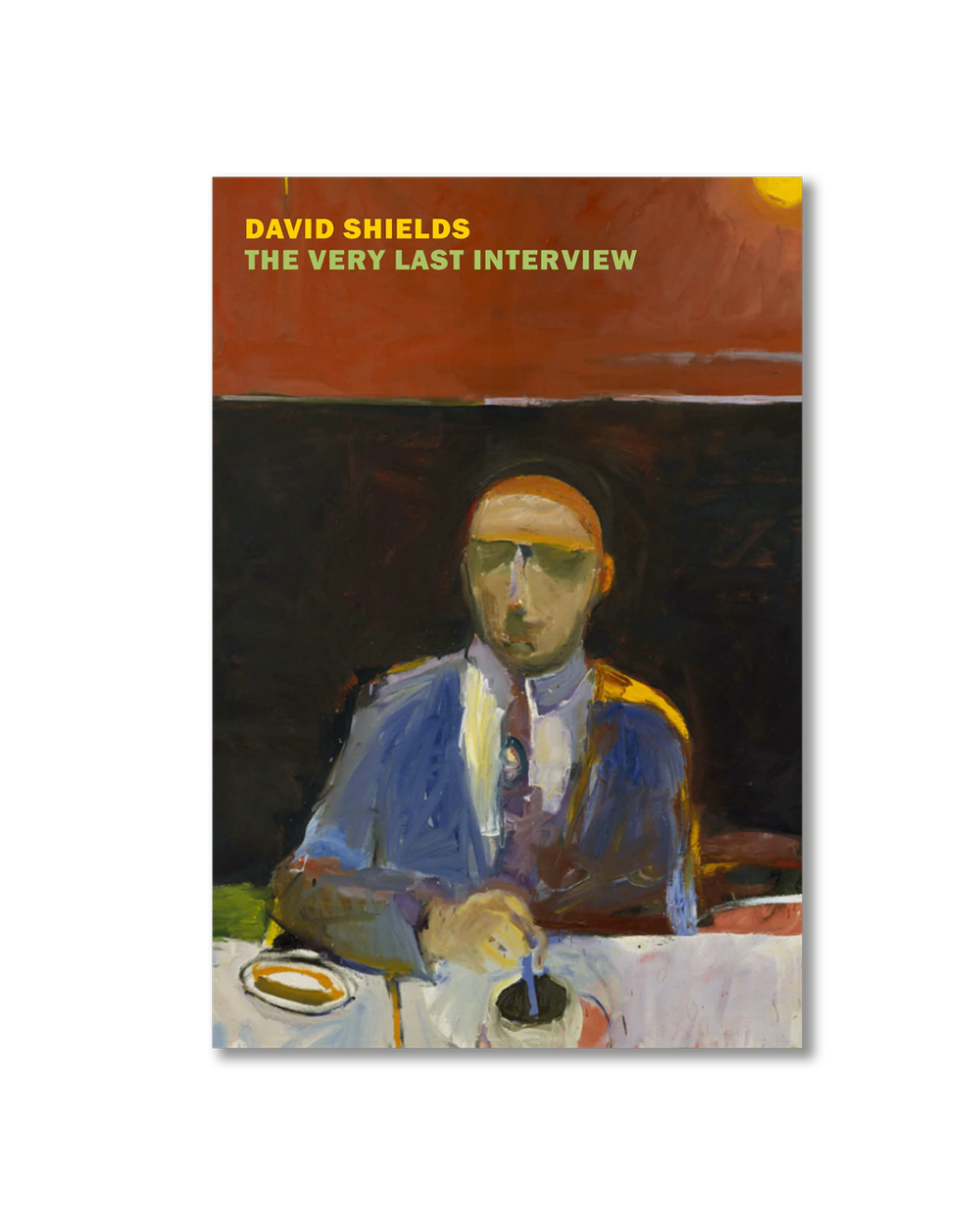

The cover of David Shields’ The Very Last Interview features a blurred man in a suit and tie, his skin an inhuman green. The lit figure stands before a dark background like the subject of an interrogation, a single light bulb swinging in a dark room. But this slippery figure eludes. He has mastered the technique of answering a question with a question. He’ll never confess.

The elusive man on the cover works as an apt representation of David Shields. For years now the essayist’s preferred method of writing has been a deliberate blurring of narrative and interpretation through nonfiction collage. The most famous incarnation of this technique remains Reality Hunger: A Manifesto (2010), in which Shields collated theories, anecdotes, and observations on the subject of media consumption, blending quotations with his own words to create a hybrid work.

For his latest book, The Very Last Interview, Shields amassed every interview he has given over the past forty years. From there, he gathered 2,700 questions and arranged them into 22 list essays organized by theme: Process, Capitalism, Jewishness, Suicide, Comedy, etc. Each short essay begins with an epigraph before the questions launch, lines running down the page. The questions are pulled out of context with no citations.

One of the pleasures in reading The Very Last Interview is a continuous “wow” over the questions people will ask: banal (“Read any good books lately?”); rude (“You weren’t raised in a Gulag or Nazi Germany or by wolves. When are you going to grow up, some might ask?”); desperately pretentious (“Is the Philoctitean wound-and-the-bow your single deepest narrative vector or only your most insistent?”); sweet (“You doing okay there, Mr. S?”); idiotic (“Could you email me every syllabus you’ve ever created?”); absurd (“Can you define ‘truth’?—preferably in one good long paragraph.”). Shields’ sly humor is evident, and one can’t help but picture precocious graduate students clutching “gotcha” questions to their breasts as their mentor teaches by holding up a mirror.

Yet not so long ago, Shields was the precocious writer leading the charge. In the early aughts, creative “nonfictionistas” were the rebels of the literary community. MFA programs rushed to accommodate the fourth genre, while the old guard dismissed methods like collage as nonsubstantive, trendy, and disingenuous.

Not anymore. In the past twenty years hybrid forms have become a mainstay, with the submission guidelines for any number of literary magazines beginning with, “Surprise us.” Or more to the point, a mug for sale at the latest AWP conference pronouncing “Fuck Genre.” Today, breaking form is less about intellectual conceit, and more often utilized as method to express queerness, trauma, diaspora, and othering in general. This evolution in American letters feels natural, even though hybrid, nonlinear narrative techniques have been long adopted in Native cultures, African American Literature, and other creative traditions omitted from the Western canon.

The Next American Essay, a once cutting-edge anthology of lyric essays in which Shields appears, is now the age of a college student, while Shields is the long-tenured professor and Distinguished Writer-in-Residence. His current long list of blurbers reads like a who’s who of his literary subset. His biography on the back flap says he has authored “more than 20 books” (no need for an exact count). The Rebel has become the Establishment.

Shields plants self-critique about his position as a successful white male writer of a now well-accepted genre. For example, “Do you not worry that this approach and stance (the self-excavation ad infinitum, ad nauseum) can become—have become—unbearable not only for the reader but also for yourself?”; and, “Is the entire workshop model an obsolete one, and if so, have you not benefited from a model that is not only deeply authoritarian and patriarchal but also inherently, racist, misogynistic and anti-democratic?”

Of course these questions are rhetorical; these are statements disguised as questions. After a while, the cumulative effect functions as a blockade against critique. A third of the way through The Very Last Interview I realized that any point I might want to make about Shields has been made before and what’s more, appropriated by Shields. He has made himself rubber and the critic glue. As an experiment, I tried to find a wedge by writing this review as a collage of sentences from reviewers over the past twelve years:

The worst sort of con man, one who cons himself into believing he's not conning us.

But he's honest and even calls himself out at times. It's a daring and unique book in my opinion with a very personal, open style that I haven't read a lot of.

I can understand why people don't like it because, as a general rule, normal people do not like self-obsessed guilty white whiners. But me, a self-obsessed guilty white whiner, myself...

While this approach makes for a colorful piece with a creative use of language and rhythm, it also prevents the work from standing on its own as a coherent and complete work.

Great example of a book that would have worked much better as an essay.

One thing is for sure though, Seattle needs its team back.

Admittedly, the Shields method takes some doing—researching, selecting, arranging and rearranging the two faces on either side to build the right vase. After a while, though, I began to feel like the blurred man on the cover. Or to be more exact, I was the convex mirror reflection of the blurred man who is a print of a photo of a painting. Yikes! I stopped myself. What was the point in continuing to write the same review others have written before me?

For all the white space left on each page, every square millimeter of the book is occupied by Shields. The reflection in the mirror is that of a literary community free to ask whatever they like, but who shouldn’t expect much of a conversation.