Interview: A Little Hello From John Lurie

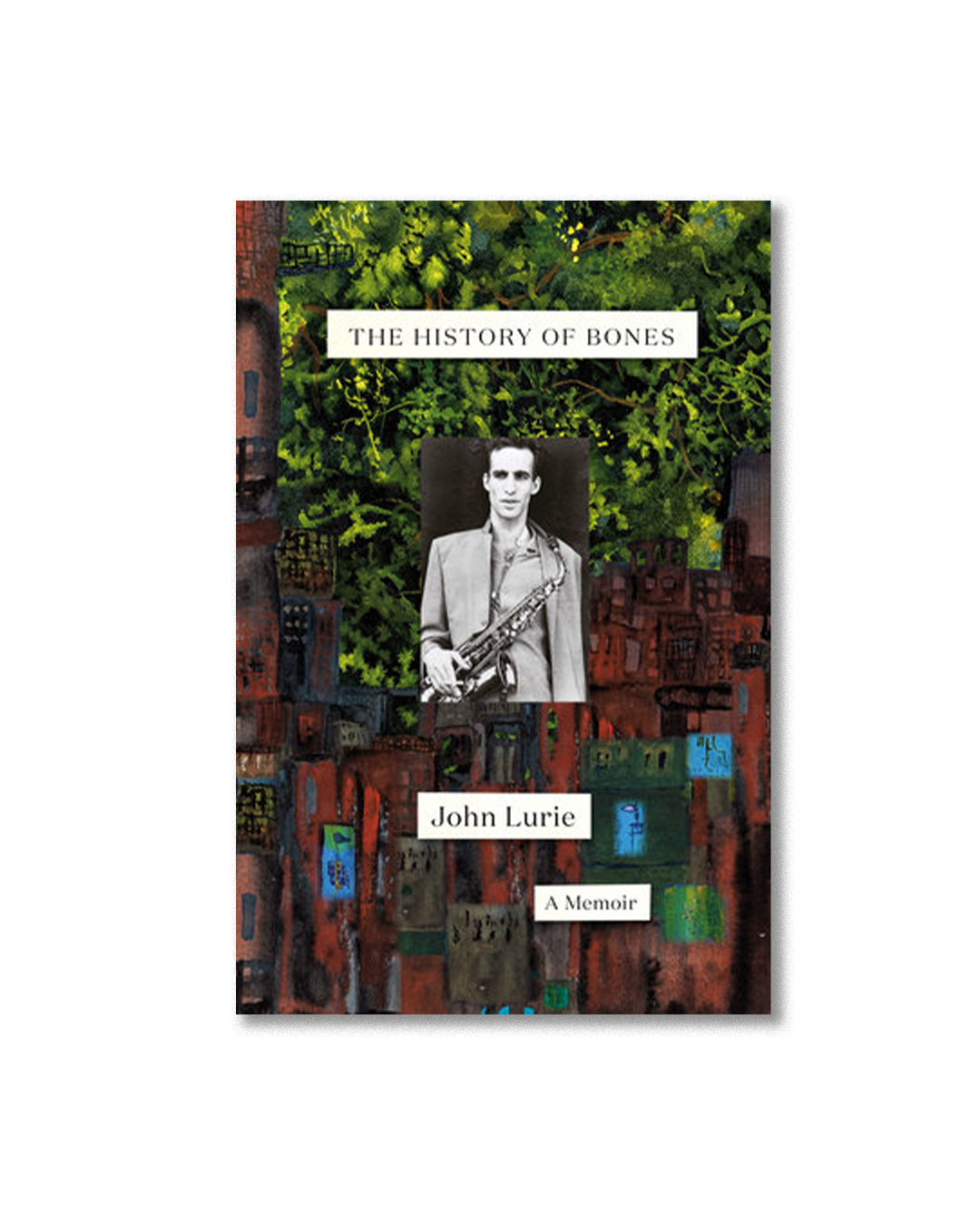

John Lurie | The History of Bones: A Memoir | Random House | August 17 2021 | 448 Pages

I recently had the chance to exchange emails with John Lurie, with the release of his memoir, The History of Bones, looming.

John Lurie is about as avant-garde, in the realest sense, of an artist you’ll find. While he spends most of the time doing watercolor painting now (which he talks in depth about in his HBO series Painting With John, whose second season is set to be announced with the publication of the memoir), he has directed (Fishing With John), acted (in films directed by Jarmusch, Scorsese, Wenders, etc.), and perhaps most importantly, music (band leader and saxophonist for the Lounge Lizards). If nothing else, let this interview be a strong recommendation to dive into Lurie’s genre-spanning oeuvre, including this book itself, his first.

The book is billed as something like an underbelly history of the 1980s avant-garde art scene in New York, specifically the Lower East Side. This scene played host to the likes of Jean-Michel Basquiat, who was quite literally hosted by Lurie in his apartment for a year. But the book is more than this; in my view, it’s like a post-beat period Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, written from the perspective of a Montaigne, taking stock of a life lived up to this point, figuring out where there was meaning, where there wasn’t, and if there is some greater truth to be gleaned that can apply to everyone.

With that I’ll get to the interview.

Note: Interviewer’s comments prefaced with “BL” and BL’s questions prefaced with “Q”; John Lurie’s replies prefaced with “John”.

Q: How and to what extent has your painting practice influenced your writing process while working on The History of Bones? I’m thinking about all of the anecdotes you shared while painting in Painting with John, where it seemed like there was something about telling stories while painting that gave them a real sense of clarity, depth, profundity, and weight.

John Lurie: I am not sure it influenced the writing process so much. There is that thing that I love with painting or music or writing, where I just feel compelled to do it.

A lot of the book was written way back in 2001 and then I had put it aside. What I like about writing is that first blast that comes out, but that first blast happened back, quite a while ago. I hate going back and reworking it. I find that part of writing quite painful and tedious. So when it bogged me down too much, I would get up and paint for a while.

In many ways painting and writing and music are very similar. But with painting it is all there in front of you. When reediting the book, I had to go “if I move this sentence to that paragraph in chapter 3 then the rest of it will work later in chapter 21 but you have to clarify X then.” You have to hold all that in your mind and sometimes the mind isn’t up to it.

Q: How did you come up with, and what is the significance of, the title “The History of Bones”?

John: Oh, it is supposed to have significance? Nobody told me that.

BL: That was, admittedly, kind of an English major-y question, but I was genuinely curious where the idea for the title came from. I’m going to back-track to your previous answer for one more broad follow up question before gearing my questions more toward the contents of the book itself.

Q: Could you please speak a little bit about the “blast” of writing that kicked off this project in 2001, why (if there are reasons besides the tediousness of editing) you put it to the side, and finally, when and why you decided to revisit it and finish it?

John: 2001 was when my health started going haywire with Advanced Lyme. Doctors couldn’t figure it out what it was for a long time. I was writing in a mad dash to finish it before I wasn’t not here any longer. But then the brain fog got so severe that I couldn’t finish even the simplest sentences and had to put it aside.

It was perhaps funnier than it is now but really angry and bitter. I went back in to take some of the bitterness out.

Q: To pivot to the book itself, at two points in the The History of Bones, you bring up a phenomenon you see in the art world and the music and film industries: The Conspiracy to Maintain Mediocrity. You mention it in relation to galleries having really boring shows, how Jean-Michel Basquiat and his art have been treated posthumously and finally, cultural gatekeeping, which "keeps people who love the artist's work away from the artist's work." When did you first notice this prevalence of mediocrity, and how do you see us breaking out of it?

John: I think it is really about the type of person who wants power above all else. So I don’t think this is limited to the arts. I am quite positive that the best possible political leaders almost never end up as the people who govern things. Those are usually shrewd and amoral people. And that is hardly just in the United States, that is worldwide, with the United States probably being one of the better places.

It seems that the people who would be actual healers, do not have the kind of skills, ego and cunning that it takes to get through medical school and then become a top doctor in their field.

With the arts, the artist may or may not be someone who wants power, but any artist who has that first on their list, is probably not much of an artist. The people who run the art world are aware that if a true and great artist were to be recognized during their lifetime, they would have immense power. So the artists who are promoted are the lap dogs, the ones they can control.

Plus an actual artist will say many true things that people in power absolutely do not want heard.

Q: What makes the prospect of a great artist being recognized in their lifetime such a scary prospect for the art world? What do you think the art world’s loss of power would look like in such a scenario?

John: One thing I have been curious about for a long time is how did Gaudi happen? Here is a for real artist whose vision is draped all over an entire city.

How did that happen? In most places during most periods, there would have been an army of bureaucrats trying to stop him rather than paying for him to make these extremely different, magical things.

BL: It has to say something about the people of Barcelona at that specific point in history, right? That they were hungry for those buildings, or they were the kind of people who were open to new kinds of beauty. Or they didn’t have the societal conditioning that would have made that kind of appreciation very difficult to achieve. Which kind of leads to my next question.

Q: In the book, there’s a touching segment where you describe Jean-Michel’s pure delight at hearing your saxophone solos you’d play in your apartment. You could see the pure expression of joy on his face, like a baby, who I come away thinking of as the best judge of aesthetic value. You’ve also remarked at length, including in Painting with John, that an inherent childlike quality is the driving force of creativity.

Basically what I’m asking is, how badly have you wanted to punch a guy in the face at an art gallery who loudly remarks “my kid could do that!” We’ve all encountered that asshole. Why is that view so wrong?

John: Nah, that doesn’t bother me. It is like the guys on YouTube who irately comment on Fishing with John - This shows sucks. That guy can’t fish at all!

BL: Not everyone is privy to the special dance and Tacho! [note for readers: reference to episode 4 of Fishing with John]

Q: You mention in the book that for much of your life, you’ve gravitated towards the “cool people” instead of the real ones. Is there a point in life where you decided to reverse that trend, and if so what effect has that had on you?

John: But it really isn’t like that. My most awkward time was when I wanted to be in with the guys on the football team in high school. But you could hardly call them the cool kids. Then in the early 80s I did gravitate to the cool people for a while.

Mostly I just want to know people with heart. And some of the cool people do have heart.

In New York City in 2002, I bet there were legitimately a thousand people who would have said, “Yeah, me and John Lurie are good friends.” But then when I got sick and was stuck at home for years, I heard from maybe ten. And to be quite honest, they were the only ones out of the thousand that I would have wanted to hear from.

BL: My grandma has always told me that you’re lucky if you can count the number of real friends you have on one hand.

Q: Off the record, we briefly touched on the topic of why you wrote the book, and you mentioned that part of it had to do with being painstakingly self-conscious when you were younger. Could you please elaborate on that?

John: In my late teens and early twenties I was horrifically shy and self conscious. I relentlessly questioned what this life was about and what I was supposed to be doing. There was a lot of self loathing.

I thought that showing that to younger people who were going through something similar could perhaps benefit from it. Kind of like if Holden Caulfield had grown up and was able to find his voice in music.

Q: In what ways would you like to see young people benefit from reading your story? Is there a particular reason why you have young people in mind as your readers? I’ll say from personal experience that so many friends (including me) who are in their twenties had little to no idea of who you were until very recently, and after watching Fishing with John, focusing on your individual performances in movies, and getting into old Lounge Lizards records, you’ve really touched, and are actively touching, a lot of people’s lives in a beautiful way.

John: Well, it is hard to tell how one reaches people. The stuff is all just sort of out there - the music, the paintings, Fishing with John.

This afternoon, my old saxophone player, Michael Blake, sent me a one minute clip of the Lounge Lizards playing live. He was saying that someone was asking the title. The thing sounded just incredible, it was one of many pieces we never got to record. The best Lounge Lizards stuff was at the end and we never were able to get into a situation where we could record it. We couldn’t get a record deal and that really bothers me that this music basically went unheard.

But this bit of a concert from 25 years ago was still floating around out there, somehow.

And I don’t know, as you get older you kind of want to help young people. Especially when it feels like they are coming into a world that is piled really high with bullshit.

I am pretty sure I am not bullshit and just want to give a little hello.