All Hat No Cattle: On The Marfa Invitational Art Fair

The West: Where fantasy displaces the real for profit.

When I meet sculptor Charles Harlan he’s sunburned and in need of a hat. I offer him the pink Marfa Invitational trucker hat I received at VIP check-in, but he declines. He’s also against the cowboy hats that are ubiquitous amongst the artists and collectors surrounding us: “Just can’t do it, man.” He shrugs. While I pontificate on the utilitarian function of my own minor-league baseball cap, Harlan smirks at me. Good-naturedly, I think. He’s taller and quieter than I expected. We’re standing outside the building that houses the third annual Marfa Invitational Art Fair, in Marfa, Texas, a town that erupted into an unlikely art destination after the minimalist sculptor Donald Judd fled New York in the 1970s and began buying up properties to display his art and that of his friends. Harlan is wearing Carhartt pants and a Marfa Hardware t-shirt he found for $20 when he stopped into the store to check it out. His appearance makes me glad I didn’t spruce up before meeting him. He wants to drive to the desert to show me Roll Gate, his new, site-specific installation. But first, he needs some shade for his head.

In the meantime, he brings me to one of his other sculptures, Wheel (2022). The piece consists of blue stones wrapped inside wire fencing, a wooden cable roll, a crab trap, and a tire, all harpooned together by an iron rod so that it looks like a junkyard hors d'oeuvre. The title of the work references the biblical story of Ezekiel’s wheel, which describes the Israelites’ exile, Harlan explains. He wanted to bring it to Marfa and let it sit on the stolen Apache lands surrounding us. Some believe the Ezekiel’s wheel story is also an Old Testament account of a UFO sighting, which Harlan hopes is in conversation with the mysterious Marfa Lights: ghostly flickers that seem to float across the desert just out of town where a viewing platform and a sign tells tourists where to look. Contemporary Marfa is awash in money from art collectors and property developers. The influx of capital has spurred vicious debates about retaining Marfa’s authenticity, whatever that might be. A common worry is that the current gallerists and other power players have sold out Judd’s original vision, turning a place meant to be apart from the art world into an exotic epicenter. To this line of thinking, the Marfa Invitational functions as a case in point: by connecting the current craze for art-as-investment with Marfa’s appeal as a desert oasis, it is perhaps the most overt attempt to monetize, and thereby desecrate, Judd’s original vision. The Marfa Lights make for a kind of counterpoint to the earthly commotion: they are a feature that money and power can’t distort, much less explain. Unless of course they’re actually produced by secret military aircraft, as one theory has it, in which case the lights are a supernatural extension of money and power.

Charles Harlan, Wheel, 2022, stone, steel, wood, vinyl, plastic, rubber, 85 x 35 x 27 inches. Photo credit: Charles Harlan.

While Harlan’s Wheel is in conversation with all of this, it’s also clearly a fun thing to have made. Harlan prods and kicks it into better alignment as he shows it to me. He’s enamored with the blue rocks and sad he couldn’t get more because of supply-chain issues with the wholesaler.

Something else that sets Wheel apart is that it’s hard to see as a commodity. If someone bought Wheel, Harlan would dismantle it into its scrapheap parts, drive them to the new owner’s house and reassemble it. The piece would have to stop being art in order to be art again somewhere else. This makes it an odd fit alongside paintings and other sculptures on display at the Marfa Invitational, all of which would look nice in a living room, and are regarded as investment opportunities as much as aesthetic objects. But Wheel resists that slippage. Where the other artworks can be seen as physical objects that are almost NFTs, Wheel is a sculpture that is almost a pile of trash. And, although this may not have been intentional, I imagine this difference as unconsciously tied to the way Wheel is displayed. It’s as if the Marfa Invitational’s directors weren’t quite sure what to do with it: The sculpture sits too near the art fair entrance, where viewers wonder if it’s on exhibit or not. In terms of Harlan’s prospects for gaining attention or making a sale, this is bad. In terms of heightening Wheel’s power, for those who do interact with it, to complicate one’s relationship not just to the Marfa Invitational, but to art, the environment, and to each other, I interpreted it as a happy accident.

•

I’ve been in Marfa for an hour by this point and have already viewed the other pieces on display. In total the art feels like an afterthought. It’s not that the Invitational has failed in its mission to bring “foremost considered artists” and “cultural arbiters,” to far West Texas, it’s just that having brought them together, the last thing anyone wants to do is stand around and look at art. The gallerists sit bored at their tables.

Among the exhibitors are some young sluggers: Emma Stern, who I hear most often referred to by her Instagram handle @lavababy, is here. She’s skulking around in the white prom dress she’ll wear all weekend. Her paintings, depicting scantily-clad women drawn with the use of Lava game-design software, are coveted by Lena Dunham. Austin Eddy is here as well, displaying a fresh installment of his bright and lumpy birds. I appreciated these when I saw them in Dallas, despite my hunch that they’re designed for the lobbies of boutique hotels—where they’ll look damn good. Evgen Čopi Gorišek is also here. Gorišek is a white, Berlin-based painter, whose cartoonish depictions of dark-skinned bodies with emoji-like faces I struggle to understand as something besides brash caricature. His paintings make me think of Mr. Bones, John Berryman’s black-faced interlocutor in his Dream Songs poems. In the worlds I inhabit, as a writer and teacher, where the ethics of representing otherness are fiercely contested, you don’t, and shouldn’t, get away with what Gorišek is up to. But, this is a different world, perhaps: A pretend place named “Marfa” where the art-set has landed for the weekend. The pieces in question have mostly already sold on web-viewing alone. Stern, Eddy, and Gorišek have struck it rich. Their weekend goal it seems is to look disaffected in the desert, shake the hands of a few people who have invested in them, and lay the groundwork for their next shows. They aren’t new so much as of the moment. It’s as if they live inside an app with the background theme “Marfa”—for this weekend at least.

•

After consulting with Darren Flook, a gallerist based in London who is exhibiting Harlan’s work, and Anna Leader, a photographer and Darren’s girlfriend, Harlan learns there’s a store called “Communitie” just a block away, where nearly all the hats around us have come from. Communitie sells a multitude of hats, not just the cowboy variety, Leader assures Harlan. His choice is between western-wear cosplay and further blistering his nose. Reluctantly, we set out for the store.

Inside, we’re offered Topo Chico and prosecco. There’s a queue of other VIPs, recognizable by their blue and gold wristbands, all of whom are seeking hats. The crowd is trying them on, collecting feedback, and offering critique. They’re snapping photos and uploading them to Instagram: #Marfa, #Communitie. I admire their practiced way of placing hands lightly on each other’s backs as they pose. If the hats were crass t-shirts, we could be on the Jersey Shore; but these are expensive western hats; this is Marfa. The nicest of the lot costs approximately $500.

In Communitie, I notice how Cowboy camp morphs into Cowboy cool if you have the dough. This is The West, I think: where fantasy displaces the real for profit. As a transplant to the state of Texas, I have a strange desire to see that displacement, which is why I’ve come here, expecting the Marfa Invitational to bring this phenomenon into stark relief.

But in the weeks before the event, I began to feel anxious. My goal, essentially, was to witness a fantasy about art, money, and landscape that other people are in the business of selling. That these people have more money, style, and taste than I do made it worse. I started to curse the lucky happenstance whereby the English department at the university where I work had a glut of unused travel funds and in turn loosened the rules for spending them, which had helped finance my VIP pass. In Communitie, my imposter syndrome reemerges. While Harlan tries on hats from the discount bin, I spend my time examining the other thing for sale: shiny rocks. I doubt they’re real—but of course they are.

Harlan selects a straw monstrosity which screams “professional landscaper.” After he’s paid for it, we stand around outside while he checks his reflection in storefront windows. The courthouse square behind us is lined with yard signs displaying yearbook photos of Marfa’s graduating seniors, entirely Latinx: a community visible nowhere in Marfa during the Invitational. The signs sway accusingly. They are a monument to what this place doesn’t have: a spot for teens to hang out. The streets overflow with the swanky, quiet self-assurance of the rich.

This is another reason I wanted to meet Harlan—to see how he’d fit in, or not, in Marfa. He exhibits often and to good acclaim, but only rarely do collectors find room for his pieces. And then there is the work he must do to exhibit at all: unlike painters who show up to art fairs with their work already hung on the walls, as a sculptor who builds primarily with found materials, Harlan must set up his own work in each particular site. And, unlike many of the other artists here, he remains broke.

•

Harlan is the 38-year-old son of a Southern Baptist hardware store owner. He was raised in Smyrna, Georgia, educated in New York, and eventually wandered back South, trailing his wife who is an English professor. He’d driven Roll Gate and Wheel to Marfa in his Ford Ranger from his home in Wilmington, North Carolina on borrowed gas money. He describes himself, by upbringing and by trade, as “a hardware store connoisseur.” At a later event, when a Texas collector hears Harlan’s backstory and suggests he buy Marfa Hardware, he politely demurs. “Oh, is it for sale?”

“Could be,” the collector says.

We’re surrounded by people who aim to buy everything, but for the entirety of the Invitational, besides the hat frenzy inside Communitie, I see no obvious transactions taking place. We’re so far down the rabbit hole of conspicuous consumption that it becomes inconspicuous—the private tapping of a “purchase” button; an unseen hand brushing another’s back.

Charles Harlan, Roll Gate, 2016, steel, 96 x 60 x 15 inches. Installed at Marfa Invitational Sculpture Park May, 2022. Photo credit: Charles Harlan.

Marfa is renowned for its mystique. Every tourist magazine celebrates this as the conjunction of desert light with bohemian quirkiness, both of which are abundant in Marfa. But the fantasy of buying everything is surely another of Marfa’s mystiques. It’s the mystique behind the mystique, if you will, and I suspect the mystique is grating on Harlan. I wonder if his new hat is intended partly to shade him from the Invitational’s garishness. On the sidewalk, he can’t believe he made it all week without one.

“Life-changing,” he says.

•

Finally, we drive out to view Roll Gate. This piece is a metal partition: the kind you find pulled down in front of a bodega after closing time. Harlan has installed it permanently, “until the wind blows it over,” in the Marfa Invitational’s new “Monuments: Outdoor Sculpture Section.” It’s the most prominent feature of “Monuments,” positioned so that you view it with Highway 90 and the Chinati Hills as the backdrop.

“Beyond them, that’s Mexico,” Harlan tells me.

The gate itself sits inside a white frame with a padlock on either side. When we return at dusk the next day, it pops evocatively during magic hour. But what wouldn’t pop in light this extravagant? Maybe that’s the point. We’re “out in the desert,” but only a mile from Marfa’s center, less than that from the Dollar General on the edge of town.

About Roll Gate, I have many questions. Does it suggest the desert is an art gallery but also a convenience store? What does it mean that the store is closed? Is the store really closed, given all I can see beyond the gate? Is it saying the art bought and sold in Marfa is no different from Doritos and toothpaste? Do the people buying $500 hats get the joke?

Harlan’s answers are opaque. First, he says it’s whatever the viewer thinks it is. Next, he’s speculating whether tumbleweeds are rootless vegetation, like giant, gnarly air plants, or if they’re the result of bushes drying up, breaking off, and blowing away. He’s stalked off looking for a better photo angle, hand on hat to keep the wind from taking it. He’s still smitten with his creation, trying to really see it, when for months he’d been imagining it here.

Eventually, I sidle up.

“So, you bolted this thing to the desert.”

He explains that Roll Gate had been sitting around his shop, and that he lugged it through several moves never quite finding a place for it, and that when the Marfa Invitational Foundation asked him for a donation to “Monuments,” it seemed like a good fit. Seeing that I’m still dissatisfied, he says, “Ok, do you know what a Zen koan is, the sound of one hand clapping, or whatever?”

I nod. I know generally what a koan is.

“Well, this is a gateless gate.”

Viewing Roll Gate, I think how, while the yard sign portraits of graduating seniors made me feel accused, this artwork causes something approaching despair. In town, I’d had a conversation with a local artist named Rory Parks who told me he was “always game for talking Marfa.” Parks wasn’t affiliated with the Marfa Invitational and described it as “an example of the most grotesque art world elitism”—an event that reduces Marfa to “a place where rich people pretend to live.”

I guess what riles me up about Roll Gate is that it seems to mock the Marfa Invitational in a manner that fits with Parks’ take, only this very take is celebrated by the Marfa Invitational. With Roll Gate anchoring the monument park, the Invitational seems to flaunt its embrace of consumerism, and it does this lightheartedly, so that you start to feel like a dolt for taking any of it too seriously. “We are rich and frivolous and this will always be so,” it seems to say. The plan is for future Marfa Invitationals to take place on this same spot, in a giant custom-made art “bodega.” This is the dissonance I was after, I guess. It’s proof of what I know but can’t quite believe: that everything is always, potentially, actually for sale, and that critiques of that fact have the counterintuitive effect of making it even more true.

I run all this by Harlan, and unsurprisingly, he disagrees. One thing I should probably know, he says, is that the Apache word chinati can be translated to mean both “pass” and “gate.” The Chinati Hills in the distance are a mountain pass and also a gate between here and someplace else. This Wikipedia discovery is what finally convinced him to install his gateless gate in Marfa. He thought it “rhymed” with the gateless gate koan that was his original inspiration, and what are koans ultimately but an attempt to hold two things in mind at once? So while it could be about late capitalist hegemony, to Harlan, Roll Gate is also about questioning our border walls, our chain link fences, and our other absurd attempts at enclosure. While I can’t fully see it this way, I appreciate his explanation, especially because it elevates the piece from cheekiness to playful righteousness. Harlan says he felt no sense of mischief in donating it to the Invitational.

•

We take a siesta, which lasts 30 minutes. In my room, I splash water on my face and change my shirt. My shoes are coated in orange dust. Soon, I’m climbing into a low-slung sedan with Harlan, Flook, and Leader. Flook and Leader ask us: Does theirs resemble an American drug dealer’s car? Only if the drugs aren’t good, we agree. We conclude that this is the car you buy if you can’t afford the car you want. It’s fast, but jittery; sporty, but cheap—an example of the car each of us has driven all of our lives. They’ve rented it because it has built-in GPS and their British phones don’t work stateside.

At the center of town, the four-way stop flummoxes Leader. She’s incredulous that right-of-way is determined by who arrived first, and annoyed that you lose your turn for pausing to evaluate. The size of the trucks opposing us heighten her misgivings. She waits until no one else is waiting before crossing. The cars behind us are polite about it. She wonders if Texans also feel that Texas wants to kill them. About Marfa she’s dubious. Earlier in the day, she’d visited the sculptures erected and curated by Donald Judd at the sprawling Chinati Foundation, built on the grounds of the former Fort Russell. She’d found the symmetry of the place unnerving, especially how Judd’s renovations inadvertently mirrored the Nazi’s expansion of Dachau. Anyhow, she says. You’re not supposed to think about that, but you do.

Our destination is a VIP dinner 30 miles away in the town of Valentine. We spend the drive getting to know each other. Flook describes himself as the rare “non-wealthy gallery owner.” He explains how he attempts to play the long game, investing where he can in artists like Harlan the way sports franchises invest in young prospects, hoping to support careers and sustain relationships. He believes in his approach, even though the Invitational might cause anyone to question its viability. He expects the art that’s been snapped up will be discarded about as frivolously as Communitie’s hats after the weekend is over. Some of these people are so rich, he points out, that the art they buy is not an investment at all.

We discuss our lives, our kids, our dogs, our addictions, our diets. As we do, I accept that while I’ve come to report on the rich, they will remain apart from me. The people I’ve found instead are possibly the most down-to-earth at the whole Invitational. At one point, Leader apologizes for being so normal. The helicopter life is not ours, is what we’re all saying; so we cling to the quotidian—maybe for self-protection, maybe as a tiny rebellion. Of course, I realize some quotient of other VIPs, a higher percentage than anyone would guess, feel similarly.

The heart of mystique is alienation. I remember my desperation to make friends during my first year of college, and wonder if I’ve undertaken to reexpose myself to that awkwardness. How else to explain my giddiness as I sit in a too-hot car, ostensibly doing hang-out journalism, but actually making friends with the people who might be more similar to me than anyone else at the Invitational? My journalistic failure is a social success.

“Like-minded people find each other,” Harlan says.

I’m relieved to join people openly disbelieving the fantasy, but also bummed not to be sucked into it entirely.

•

Speeding west, we pass a monument for the movie Giant, the 1956 epic about ranchers ceding to oilmen that was set and shot here. A huge wooden cut-out of James Dean, shotgun across his shoulders, rises from the scrub brush. Another cut-out depicts Elizabeth Taylor, hands on hips, imitating a frontier woman. A third shows the Reata mansion owned by Rock Hudson’s Bick Benedict.

There is, I’m noticing, a penchant for standing-up unlikely objects in the desert as if for further consideration. The landscape itself lends awareness to the interplay between the pretend and the real. Prada Marfa, the fake Prada outlet erected by the Scandinavian art duo Elmgreen and Dragset in 2005, sits a few miles further down this same road. The building is an art-object, not commissioned by or affiliated with the fashion brand. It is another gateless gate, one that Roll Gate complements and questions. The description outside Prada Marfa reads: “The structure includes luxury goods from the fall 2005 collection. However, the sculpture will never function as a place of commerce, the door cannot be opened.” But this is now a lie. The Prada Marfa was opened when it was looted soon after its dedication. Through theft, it did function as a place of commerce. Now the goods inside consist of only left foot shoes (currently $1100-$1850 for a pair) and handbags missing bottoms (handbags with bottoms retail for $925-$4600).

Since then, Prada Marfa has become mostly an Instagram backdrop. The questions it asks about elite consumption have been answered with exotic images and more consumption. Instead of existing as a “rumor in the desert,” as Dragset has said about the intention behind it, Prada Marfa has become well-known enough that there’s a 2018 Simpsons episode in which the cartoon family drives by and discusses it. This was a big moment for Marfa, hailed by some as the town’s arrival in the mainstream. The Simpsons’ visit did after all occur the same year the Marfa Invitational started.

•

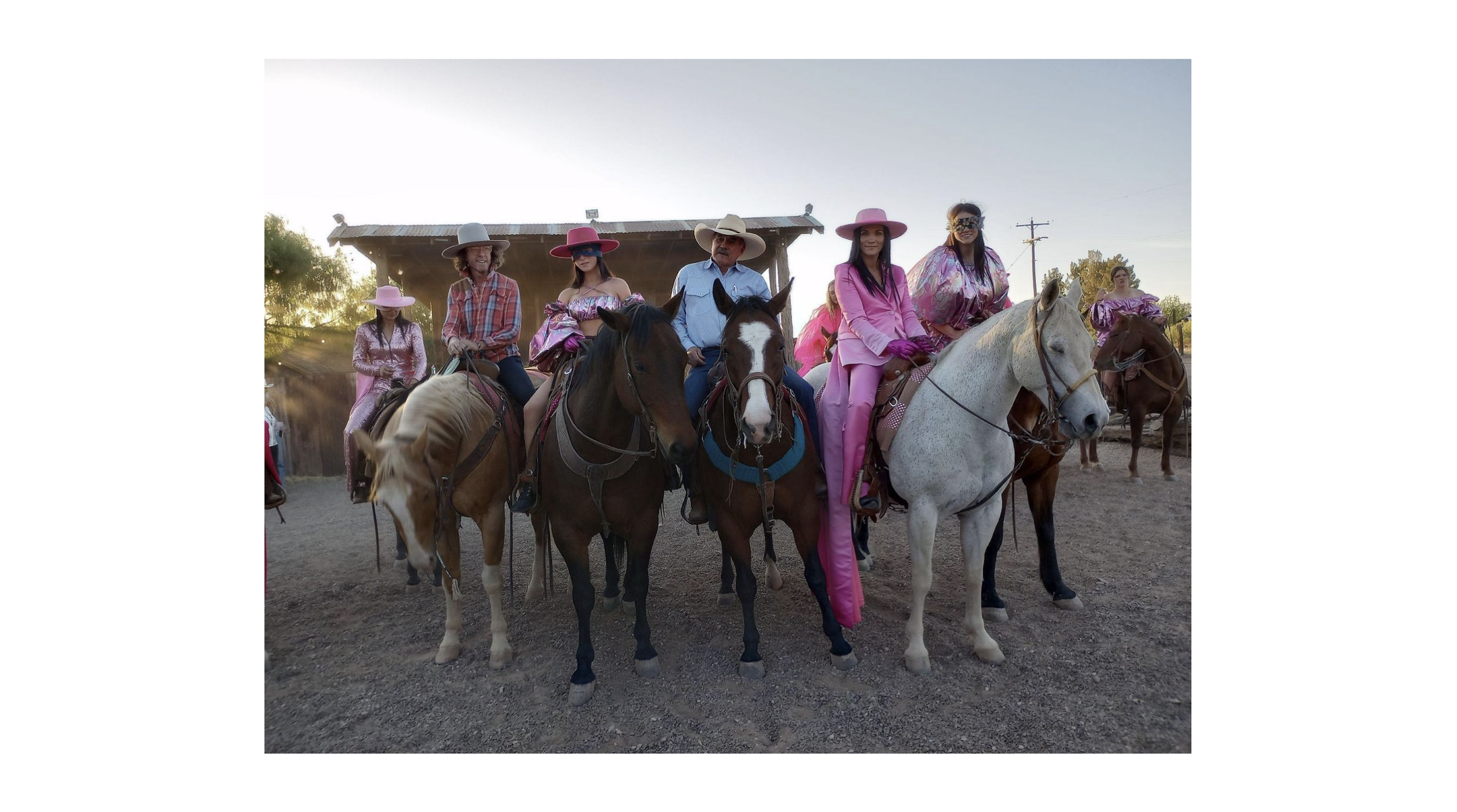

Have you seen the music video for the Guns ‘N Roses song, “November Rain,” where Slash rips a guitar solo in front of a desolate desert church? That’s what our destination resembles, except it’s not a church, it’s the 115-year-old Valentine Mercantile, which is now an event space. Inside, we’re served “ranch water” made from wine-barrel aged tequila before viewing a horseback fashion show held by the designer Cynthia Rowley. She’s outfitted 20 models, “the finest riders in all of far West Texas,” in pink scarves, bikini tops, and Zoro masks, so that they resemble a cross between Cirque du Soleil performers and the warrior princesses in Mad Max. They ride in several furious heats beside where we sit in teepee-like party tents.

Everyone goes silent when the riders reenter the corral and stand on their horses. In their outrageous getups, several of the riders rise while their horses turn slowly. The riders’ stillness is impossible to overstate as is their closeness to the crowd. This is the equivalent of their end-of-runway pose. None of them risks a smile. Their concentration is almost obscene.

Soon, they’re back in their saddles, posing for more photos. The sun is behind them, and they glow. They’re joined by Michael Phelan, the Marfa Invitational’s founder and director, also on horseback. Privately, I’d been referring to Phelan as “Mr. Marfa” ever since I found a photo of him in The New York Times standing at sunset in the Marfan wilds. He’s riding a brown, painted horse, and looks like a twee Michael Landon. His hat is the most exquisite I’ve seen. I can’t imagine the riding lessons he’s had to appear so at ease.

Riders in designer Cynthia Rowley's horseback fashion show, Valentine Mercantile, Valentine, Texas, May 6, 2022. Photo credit: Jack Christian.

Mr. Marfa does not address us. His presence is enough. Lightly, he touches the backs of the models as they pose. He is our patron, the man who bought a New Yorker’s dream of Texas and invited us to share. It feels as if we’re living a party scene in a Wes Anderson movie. We’re all characters playing ourselves, deep in an expensive cognitive-behavioral trick. I take more pictures and all my pictures are populated with people also taking pictures so that all my photos are of other photos being taken. The feeling is of levitation. I imagine it as a synonym to the brief weightlessness experienced aboard a Space X rocket. Our escape achieves exit velocity. We loot reality in an orgy of images.

•

After the show, everyone knows levitation is fleeting. I find Harlan near the train tracks. He’s talking with the Texas collector who earlier suggested he buy Marfa Hardware. The collector is going on about how hard it is to get building materials out here. We’re three hours from El Paso, three from Midland: a royal pain either way. He mentions his other properties spread across the state, and his cadre of Airbnbs. Next, he’s speculating: where could the next Marfa be? Second, after theorizing about Marfa, this is the most popular topic of conversation. Harlan feigns interest, so I jump in. I suggest the next Marfa will have to be somewhere even more inaccessible, a daylong trotro ride from Lagos, maybe. The Texas collector tells me I’m correct, but he’s not interested in that. He’s imagining a place like Albany, Texas: a town of 1500, 35 miles east of Abilene. Albany has a well-preserved downtown, a coffee shop, and a thirst for new investment.

“I’m talking about a Marfa you could visit on a daytrip from Dallas,” he says.

Before the end of the night, the Texas collector mentions a possible commission for Harlan to come out to his Hill Country ranch and build something to “really make his neighbors scratch their heads.” This is the one bite Harlan will get.

The last I see of Harlan, he rises from the table at the next night’s “Visionaries Dinner,” just after Mr. Marfa has finished thanking the “luminaries” and “tastemakers” gathered this weekend. It’s been fun, Harlan says, but he’s had enough. Enough glitter. Enough schmoozing. I wondered how a sober, married introvert with only spare delusions of grandeur would acquaint himself with this crowd. Mostly, he wouldn’t. Instead, he’ll go looking for the Marfa Lights. He'll sit on the viewing platform off Highway 90 for two hours, thinking at every moment that they’re about to appear, but they never do. The next night however, once his truck is packed and the art mob is gone, there they are.

“Just kind of dancing, a hundred yards out.”

On my own way out of town, I stop in the GetGo, Marfa’s high-end convenience store, for an Advil and a postcard. The postcard—the only one they have—is a print of their own storefront and costs $5. The cashier chuckles at me for buying it. She’s lived in Marfa almost all her life. About the explosion of galleries and tourists she says, “I get it and I don’t.” On the one hand, everything being so posh keeps away the riffraff, and she’s never had to lock her doors. On the other, she can’t afford to eat out and feels pitied sometimes by the visitors she rings up.

“I get it and I don’t,” she says again, and wishes me safe travels home.