Ultranatural: Telling the Forever Story

Although she would later win a National Book Award, classmates exclusively remember our high school English teacher as the woman who taught for an entire day whilst enshrouded in a black veil.

It was the late ‘90s and we were middle-class Midwestern teens, a homogenous group whose focus in English class was less attuned to the mysterious questions of literature than to the certainty of our looming AP exam answers. Ostensibly, our teacher donned the garment to add a sort of experiential dimension to our analysis of “The Minister’s Black Veil.” If she assumed the eerie heft of Hawthorne’s tale about Mr. Hooper (a Reverend who one day decides to wear “two folds of crape, which entirely concealed his features, except his mouth and chin”) would be lost on us, she was right. We could identify the key features of a Transcendentalist text, but we called it transcend-dentist-ism.

We were idiots, largely because we did not even begin to know what we did not know. This cognitive bias, the Dunning-Kruger effect, asserts people who don’t know they don’t know what they are doing tend to be confident that they’re doing a pretty good job and thus perform poorly. People who know they don’t know what they’re doing lack certainty but gain curiosity and thus perform more successfully.

Our English teacher was soft-spoken and very sweet-faced. I know now that when she was not in the classroom, she was working on a book of poems about angels and uncertainty. Because she was normally such a gentle presence, our smug sense of analytic confidence dissolved as we tried to direct our answers to her occulted face. Our fundamental “error about the self”—our belief that all the information needed to understand stories could be found within the stories themselves—was heightened by our teacher’s creepy lack of response.

Faced with no face, we finally turned inward, where we were unexpectedly introduced to a foreign feeling: doubt.

•

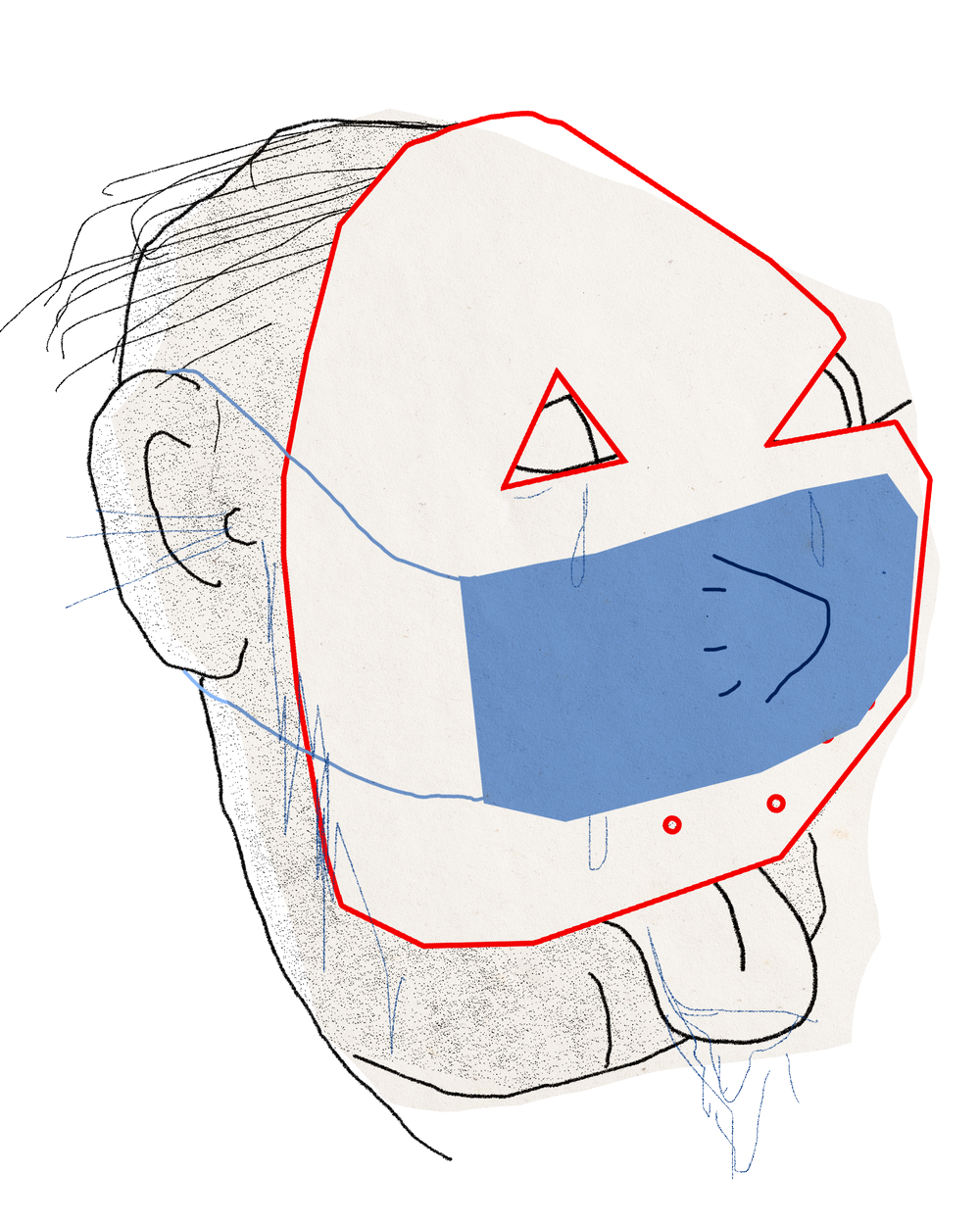

Intellectual uncertainty turns out to be a hallmark of masklophobia. This fear generally emerges around the time children learn to develop facial recognition skills, which is of course also when clowns, mascots, and Halloween costumes are most prevalent. This texture of childhood terrifies not because of what it reveals, but because of what it doesn’t. Because intelligence conveyed via microexpressions provides crucial information about the trustworthiness of others, an encounter during a child’s formative years with a person whose face is concealed can lead to panicking doubt about the identity of the mask-wearer.

For children, masklophobia causes a fairytale-like estrangement. The more you think you know someone, the more the mask distances them—makes them not just strange, but a stranger. For adults, the effect is more uncanny. You know something is amiss, but you also know the missing knowledge is somewhere inside you; the face beneath the mask is known—familiar, even. It’s the compulsion to not know what we certainly know that unnerves.

Hawthorne describes the parishioners in “The Minister’s Black Veil” as “so sensible…of some unwonted attribute in their minister, that they long for a breath of wind to blow aside the veil, almost believing that a stranger’s visage would be discovered, though the form, gesture, and voice were those of Mr. Hooper.” They speculate that the Reverend must fear even being alone with himself. They’re right—he avoids mirrors or seeing his reflection in pools of water.

The mask, then, conceals some fundamental aspect of the wearer’s nature not just to those who encounter him, but also to the wearer himself. It’s an inverse mnemonic device: a reminder to the wearer to remember that there is much they cannot remember. Absent consistent proof, the masked person’s sense of self erodes and is replaced by what Hawthorne terms “an unsought pathos [that comes] hand in hand with awe.”

By 1836, the year Hawthorne published “The Minister’s Black Veil,” the idea of “awe” had taken on a Biblical cast. It encompassed the enormity and terror of encountering God himself; with this development came sublimity and the idea of approaching the self with a sense of scope. To stand as a black-coated figure in an Edmund Burke painting, miniature against the enormity of the universe.

It is in our attempt at recollection of our own face that we might become aware of our uncertainty; that we might begin to comprehend the smallness of what we know against the vastness of what is.

•

Claude Lévi-Strauss claimed masks as “the medium for men to enter into relations with the supernatural world.” Perhaps this is why masks are often used in rituals of transformation. The information conveyed by a face crossing a threshold must be obscured; the act of slipping into a new identity (from, say, bride to wife or inmate to executed) is both deeply personal and profoundly public. To change, one must be witnessed as one was before and as one is after. A narrative is drawn between then and now, but in the in-between, there exists a bridge that cannot be crossed with another person. An inherently unobservable moment.

Former The X-Files researcher and current paranormal investigator, John E.L. Tenney, argues that often beings or events we term supernatural (ghosts, UFOs, witchcraft) are actually ultranatural. They are desperate to be seen and remembered; to inscribe themselves in space or narrative. The supernatural exists only beyond the observable universe, like the absence of God, in a realm we have never seen.

•

To be witnessed is to be known, but to be occulted is to be sacred.

Maybe this is why we claim, “there are no words” in the wake of tragedy. We become “speechless” in our grief because loss is, inherently, characterized by incomparability—it pushes right up against what we did not know we did not know, and therefore have no language for. Necessarily, there is a slippage of meaning itself in moments like this. Links in the chain of thought begin to dissolve. This softening of the chain is both disorientating and, simultaneously, a perverse freedom.

Unshackled from the linear logic of the chain, our minds try out new narrative shapes. A hope that the dead haunt us, for example, is akin to a palimpsest—layers of time happening atop other layers, striated history. Or, it becomes comforting to imagine we knew the deceased in a past life and will know them again in the future—not a storyline, but a storycircle. Nietzsche’s eternal return. Conversely, to be visited by the dead in dreams is to stop believing in narrative shapes at all, but to accept a porousness through which anything can pass. We lose our addiction to that sticky narrative impulse, the compulsive “and then what?” in favor of the dreamier “when it arrives, will I know?”

After a sudden death in the family, in the interval before experience changed shapes, I lay with my husband in our darkened bedroom. Even though I did not know what to say I found myself saying, abruptly and with force, “We had better finally go see those horses.” My husband knew what I meant immediately. A few months after we’d started dating, we’d driven to the Ozarks to see a herd of wild stallions.

White horses that have roamed the same natural spring for decades, elusive animals described by locals as ghosts in the river mist.

I think I must have demanded we drive five hours into the dense Missouri forest because we hadn’t been able to find the stallions when we’d tried seven years before. They’d stayed at the edge of our minds, veiled; a known unknown.

It felt like there would be some solace in seeing the supernatural, reducing the scope of the universe. Finding more to experience to name, to know.

•

About two-thirds into our trip the highways cleared, the sky widened, and I was seized with that Burkian feeling of entering a space so dense with being that I could not organize my own sense of identity against its many points.

It was about this time that I began to notice handwritten poster board duct-taped to passing semi-trucks as well as painted signs at the cusp of farmland and highway. Being from the Midwest, I’m used to farmers’ fondness for handmade propaganda, which often takes the form of a poem, lines spaced out at fifty-foot intervals so the final hard rhymes really hits. For example, off I-80, the grim “take our/ guns AWAY/ and criminals/ will PLAY.”

It’s so rare to see one of these signs that aren’t pro-gun or pro-life that I can easily remember the one time I did (a single line: “my spouse is away”). The roadside rhetoric I’d grown up with, however, had recently been overwhelmingly replaced with anti-mask sentiments. Unlike their cadent antecedents, these signs weren’t “strongly worded” or even political. In fact, they were largely not rhetorically fallacious in any way.

These signs were far rawer in their plea. Often, they simply demanded: TAKE YOUR MASK OFF. They made me think of the blunt warnings posted around nuclear fallout zones in the southwest. Wild transmissions sent from someone who realizes they now know something that will permanently change their way of knowing. A final bid to keep the world as it was before, to hold the line, maintain the narrative.

This is, of course, the last gesture of the grief-stricken.

It’s what we do before we admit there are “no words.”

•

Out in the wilderness, I thought of a line from the poetry collection my English teacher published the year after I graduated high school: “Granted, there are some sadnesses / in which I do not long for God.” There’s a radical inwardness to this sentiment that makes me think of Gertrude Stein’s dictum: “act so that there is no use in a centre.” A suggestion that there is a shape of being that occurs after grief in which we do not appeal to the hierarchy of divine solace.

Perhaps speechlessness in the face of grief is not so much an effort at what I have suggested to be “perverse freedom” as it is an act of sacralization. When we don’t talk about what we don’t understand, we also don’t try to make a narrative out of our experience. We keep it behind the mask, in the place of flux; the space where transformation can always be occurring.

•

A real clergyman, Joseph “Handkerchief” Moody, may have inspired Hawthorne’s Mr. Hooper. After accidentally killing a friend, Moody put on a black veil to attend the funeral and, in a gesture of penitence, never took it off. Unlike Moody, Hooper doesn’t reveal the reason why he took to the veil until he is on his own deathbed, when he finally explains that it was supposed to be a symbol for all the secrets the entire town has kept in their “inmost hearts.”

At sixteen, I thought this was a pretty pedestrian conclusion.

But now, rereading this story for the first time in over twenty years, not just decades away from who I was then, but also what the world was—a place where communication took more time, objects could not be conjured with a One-Click button, and to talk to a friend on the phone you actually had to, well, talk—I notice that as Hooper ages and suffers from dementia, Hawthorne makes a point to note that, even “in the wildest vagaries of his intellect, when no other thought retained its sober influence, he still showed an awful solicitude lest the black veil should slip aside.”

The last thing Hooper remembers to remember is that the dimensions of the self are so vast, the “inmost hearts” of ourselves and others so unfathomable and occulted, we will never know what we do not know. We can, though, remember we don’t know it.

The shape of the non-story—the one in which we “do not long for God”—is perhaps the most organic. A crystalline structure in which experiences bounce and reflect, their entirety never encompassable in any single moment; ever pointing toward the experience we haven’t had yet—but could, if we were willing to accept sides we cannot yet comprehend exist.

Surely this happens alone, under the mask, in the place where we might transform into a form to meet ourselves; where we might, then, prepare a self to meet the world. Or, I suppose to quote another poet I was introduced to in the same class where I read “The Minister’s Black Vale,” “to prepare a face to meet the faces that we meet.”

•

Again, we failed to find the stallions. Maybe we never will. Maybe life will take us too far away to ever get back to them, maybe the herd will go extinct, maybe any number of unanticipatable events will occur.

It’s this very unknowability, though, that creates a sacred contour in my experience. That allows for a shapelessness in which any shape might, suddenly, take form. A narrative of numinous nebulosity; a forever story.