Where Life Ends and Art Begins: On Rachel Cusk's "Second Place"

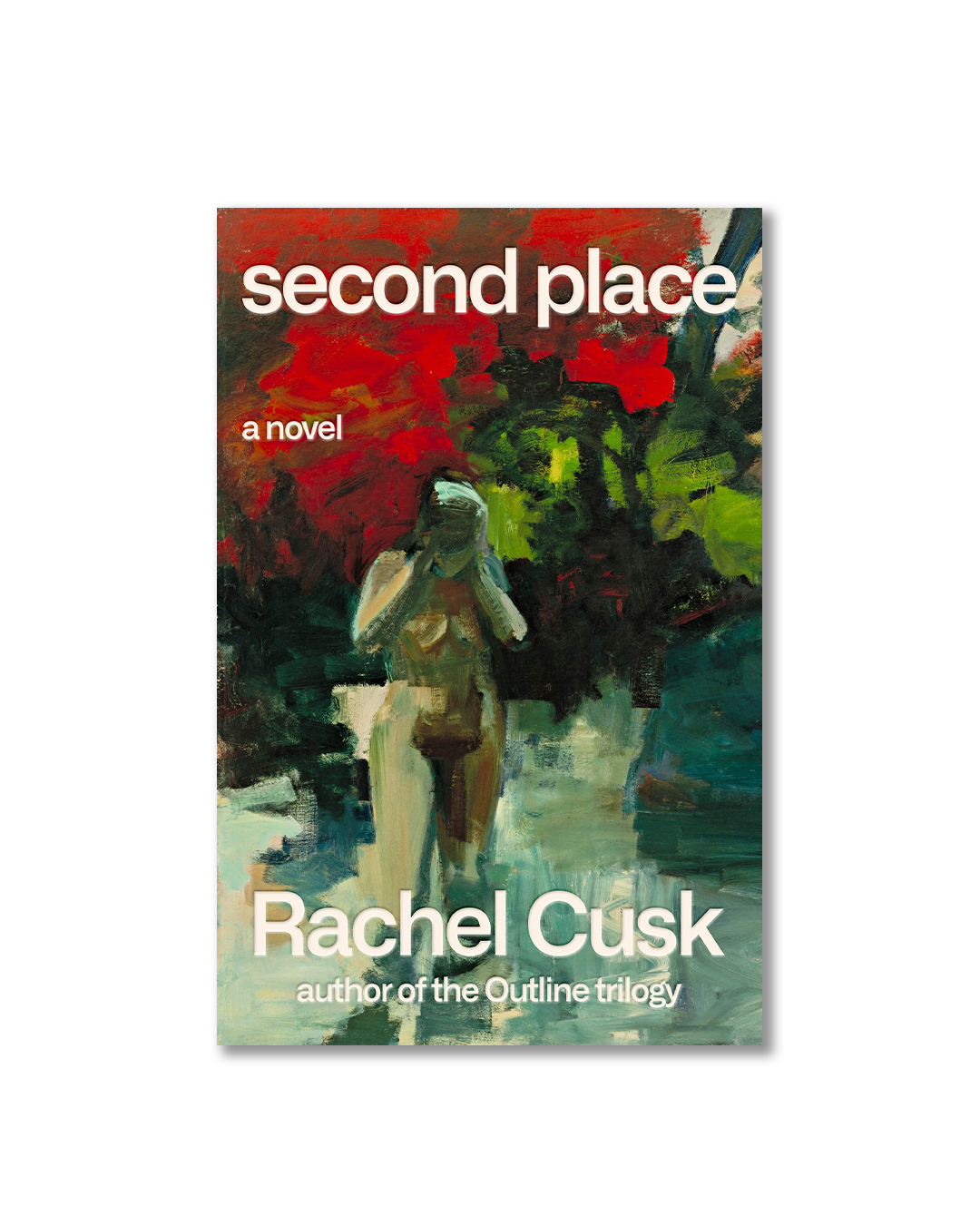

Rachel Cusk | Second Place: A Novel | Farrar, Straus and Giroux | 2021 | 192 Pages

The painter Richard Diebenkorn once described his process: “I don't go into the studio with the idea of 'saying' something. What I do is face the blank canvas and put a few arbitrary marks on it that start me on some sort of dialogue.” Rachel Cusk’s new novel, The Second Place, is its own kind of Diebenkorn, for its meaning comes from the conversations that happen not just between the characters, but also between concepts—painting and writing, lightness and darkness, art and life.

Conversation is not a new preoccupation for Cusk, whose most recent and critically acclaimed work, her Outline trilogy, is constructed from exchanges between the narrator, Faye, and the people around her. What thread these encounters together are not the characters, who rarely recur, but the themes that emerge like a color palette. Whenever the story threatens to reveal too much about Faye (as in the last book of the series, Kudos), the plot cuts short, so that our vision of the narrator is primarily based on what others say to her; this “annihilated perspective” renders her nearly immaterial, an entity composed entirely of style. The narratorial absence is part of what compels one through the novels, for it acts like a filter, distilling all other people’s tales down to their most philosophically bare, their most ethically ambiguous, their most painfully isolated.

The narrator-sized hole Outline leaves, Second Place boldly fills in with a woman, “M”, whose proclivity for snide remarks, moral judgments, and myopic obsession constantly remind us that we are located within a human, not merely a quivering thread of ideas. Having a narrator immersed in the action renders her vulnerable to scrutiny, an antithesis to the impenetrable Outline narrator. This new character-narrator elevates one of Cusk’s central concerns: How can looking at the world reveal to us something about ourselves?

In the book, the question is posed literally, when the narrator invites a famous painter, “L” (referred to, in Cuskian fashion, only by his first initial), to live with her and her husband on their isolated property, a marsh out of the way of civilization. It is not entirely clear what the narrator hopes to gain from this visit, but it is clear that she places a lot of stock in L and his vision. She writes to him, “I would like you to come here, to see what it looks like through your eyes.” In one sense, she hopes this man will be able to depict some truth about the place, and—perhaps in the process—that he will help her see herself. When L shows up, however, it is with a certain disdainful gruffness, and a hot, young, female companion, behind whom he hides for much of his stay. The rest of the book consists of the narrator, her husband (Tony), L, and L’s babe-y friend (Brett) cohabitating at the marsh with M’s daughter, Justine, and her boyfriend Kurt.

While the dynamics of Second Place afford it more of a traditional plot than Outline series, the true story of the novel is an emotional landscape: the narrator’s faith in L, her constant disillusionment with him, and the misdirection and triangulation that occurs between the different figures on the marsh. If the book were a painting, it wouldn’t be the single, pure line that our narrator hopes to draw between herself and her painter-in-residence, but more like a web representing the different characters and their odd angles of collision. All these social confluences force our narrator to weave in and out of identities. Whomever she looks at reflects back at her a different self: with Justine, she can be both a resentful and proud mother; with Tony, she is often reminded that she is a divorcee, wronged by past lovers; Brett induces jealousy about M’s femininity, and maternal affection. Internally, she in turn seeks freedom, and sometimes merely a “feeling of invisibility.”

The dissonance of these identities emerges most in conversations between L and the narrator, which retain something of the philosophically oriented, absorptive quality of Outline, perhaps because he does most of the talking. In these exchanges, the narrator both expects to be “recognized” for some ineffable quality, and yet is also reminded of her own “unattractiveness,” her “used-up female body” near him. Her experience with L is captured by the question she asks early in the book: “Why do we live so painfully in our fictions? Why do we suffer so, from the things we ourselves have invented?” In this case, the imagined experience with L—that they might transcend gendered boundaries—is her fiction, but also, perhaps, is any identity inhabited for too long. The suffering is the feeling that she is being misperceived, especially by L, with whom she expects a deeper level of understanding, the connection she feels when she looks at his art.

Literal conversations between characters introduce figurative ones between freedom, motherhood, control, and creation throughout the book. More essentially, Second Place is a reflection on the dialogue between life and art, as the narrator contends with the tenuous relationship between the act of living and the act of creating—one dictating the other like the play between the shade and the sun at the marsh, “in one of those processes of almost imperceptible change that occurs in the landscape here, whereby you feel you are participating in the act of becoming.” The physical landscape, in our narrator’s eyes, “often resembled a painted work by [L].” When she looks at the marsh, she thinks, “I was in a sense looking at works by L that he had not created and was therefore—I suppose—creating them myself.” Parenthood, too, is art-adjacent, what the narrator calls “the bringing of things into permanent existence.” Thus, the play of light on the marsh, the experience of motherhood, and the simple act of observing the world are all forms of “partial creation” for her. Cusk reiterates a position that she has taken before—that there is very little difference between writing and living; that they may be, in fact, the same.

The conversation between life and art isn’t so metaphorical; the whole book is directed to a recipient, Jeffers, who never appears in the story himself, but whose presence is homage to Lorenzo in Taos, a 1932 memoir by Mabel Dodge Luhan. In that book, Luhan writes to the poet Robinson Jeffers about her time with writer D.H. Lawrence in New Mexico. Luhan places faith that Lawrence’s artistry will “make articulate an inarticulate land [of New Mexico]” but, in the end, the book might be a more accurate portrayal of Luhan’s own psyche than that of Lawrence. While Cusk has been criticized for the obscure reference to another drama-between-artist-writers, the presence of Jeffers helps direct us to themes that concern Cusk: the unwieldiness of art, how it can take on new life after the artist has released it into the world (much like a child), and how a portrait of someone else can end up becoming a self-portrait. As she revives Luhan’s themes in a modern setting, the boundaries between L and Lawrence, Luhan and Cusk, New Mexico and the marsh of the Second Place become porous. Thus, she enters herself into a literary conversation between artists living and dead, a conversation that asks: Where does life end and creation begin?

That question has plagued Cusk’s artistry, which itself cannot be completely disentangled from her life. Outline’s overwhelmingly celebratory reception threatens to overshadow the legacy of Cusk’s past as a memoirist. In A Life's Work: On Becoming a Mother (2001), Cusk’s ambivalence about motherhood earned her public scorn from the reviewers for whom maternity was best left an unadulterated joy. Even more personally, her book, Aftermath (2012), laid bare a devastating account of her divorce for the public to dissect. Translating life into art translated into personal deterioration, and, as she told the Guardian, “creative death.” It took her three years to work up to Outline, where the self that had caused her so much trouble was notably absent. It makes sense that, after delving into the almost entirely self-less, Second Place shows signs of a self becoming more firmly located within art (she is known to vacation at the marshy outskirts of the Norfolk coast). Cusk seems to be doing a delicate dance, ever so tentatively, inviting the world back into conversation with subject of her art. That is, her life.

It is fitting that the central dialogue in the new book is between a mother and an artist—the two identities Cusk has very publicly grappled with (and also the two characters who happen, coincidentally, to have been gifted anonymity). In the book, the narrator often feels that she and L have some deep resonance; she has a sense that she, the mother, and he, the painter, share something vital. Perhaps, then, Second Place is a sly return to the radical truth of Cusk’s previous autobiographies, this time in the form of a personified internal conversation between Cusk’s authorial identities. With this framing, Cusk, the mother and divorcee of Aftermath and A Life’s Work, seeks to converse with the pure artistry of Outline. While the conversation between the domestic and the artistic proves disappointing for M within the plot of Second Place, its publication for Cusk, the author, might be the brushstroke that starts to reintegrate the previously fragmented facets of her art.