The Deflation of Spatial Imagination: On Columbus’ Future in “Ready Player One”

Perhaps the best place to view the future of Columbus, Ohio is from the vestiges of its fictionalized futures in Ernest Cline’s Ready Player One (2011) and its sequel, Ready Player Two (2020). Cline’s dystopian, neo-cyberpunk Columbus is not a sharp turn away from the city’s current urban conditions. If anything, it’s a rather natural, albeit exaggerated, continuation of its current trajectory.

Maybe more disturbing than the apocalyptic thought of humanity coming to an end is humanity continuing as ‘normal’. This is the most horrifying feature of the genre of cyberpunk. Cline’s future landscape is so grim that a vast majority of the population spends almost every waking moment inside an alternative, virtual geography: the OASIS.

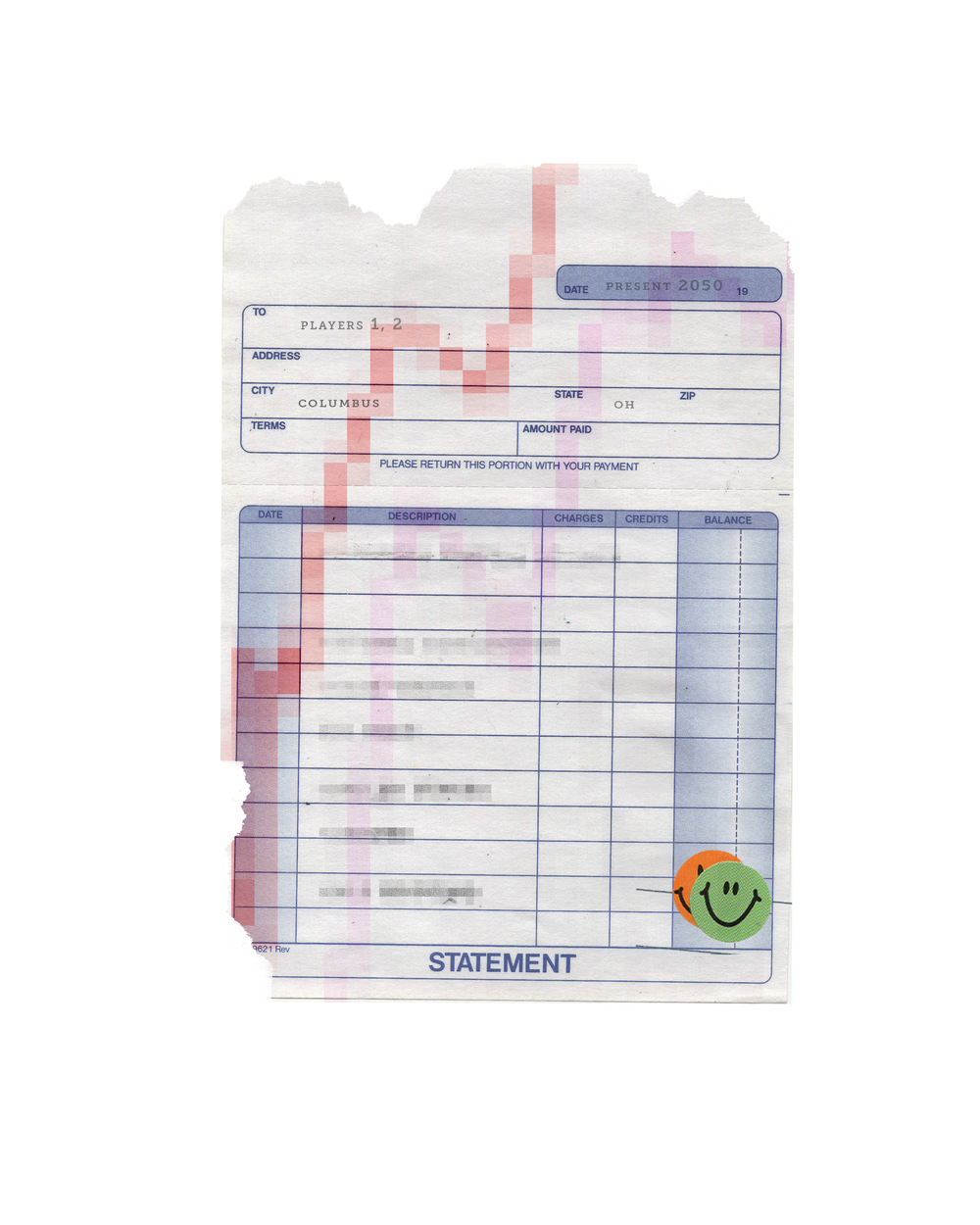

Ready Player One is also the story of Wade Watts, an impoverished high school student whose extensive knowledge of 1980s culture wins him a Willy Wonka-style contest. Watts is the first to find the hidden easter egg that sparks the quest to find three keys that together reward the winner with a fortune and control of the OASIS, but here Watts’ story is a portal into the future built environment of Columbus and the virtual geography to which its residents escape. It’s neither a utopia nor the post-apocalyptic hellscape of Mad Max. What we see in the dystopian Columbus of 2050 is a geography that’s mostly the same as today.

Virtual Geographies

As the world becomes increasingly destabilized by climate, economic, and political degradation, big tech has only increased in profitability. In Cline’s books, the big tech companies Gregorious Gaming Systems (GGS) and Innovative Online Industries Inc. (IOI) reap enormous profits from the “collective means of escape” they provide to the masses. One of the main characters, Art3mis, refers to the OASIS as the “Opiate of the Masses,” a paraphrase of Marx’s statement that religion is “the opium of the people.” Far from calling religious people drug addicts, Marx was referring to a very real need for a kind of escapism in the complex and miserable conditions of our existence. The OASIS acts as a rather profitable religion in the book, Watts describing it as an “open-source virtual utopia.” IOI, the company who wants to take over GGS, is trying to ruin it and turn it into a “a fascist corporate theme park where the few people who can still afford the price of admission no longer have an ounce of freedom.” However, the reality of the virtual OASIS is not as bright as Wade makes it out to be.

The OASIS is a virtual universe split into twenty-seven core sectors, each containing thousands of virtual planets varying in size. Many planets are designed by OASIS employees to reflect themes. There are dozens of planets, for example, designed to replicate specific regions in pop culture, including Planet Shermer (based on John Hughes films, most of which take place in the fictional suburb of Chicago, Shermer, IL), The Afterworld (a planet based on Prince references), Planet Arda I (based on the first world of middle-earth), and thousands more. There’s even a planet called EEarth, a very detailed replica of our planet, making virtual vacation a major industry. But most planets have a single theme for the entire planet like the ones mentioned above, my favorite being planet Middletown—a planet covered in 512 replicas of Middletown, Ohio, specifically modeled in the 1980s (where/when the game’s founder, James Halliday, grew up). There are cyberpunk planets that are just one giant city, planets with just nature, and planets that abolish the contradictions between town and country. It’s everything a geographer or urban planner would dream of or absolutely detest—a buffet of spatial organizations. Its fragmented and chaotic nature is oddly similar to what Rem Koolhaas called junkspace: “it is subsystem only, without superstructure, orphaned particles in search of a frame-work or pattern.”

But when it comes to inhabiting this virtual geography, there are nonetheless many barriers similar to that of the real world. The OASIS derives its revenue from two main streams: transport fees and virtual real estate, referred to as “surreal estate.” (Perhaps unsurprisingly, the revenue sources were left out of the movie, keeping an image of virtual utopianism intact.) The connection between real estate and transportation under capitalism has long been understood. Even in the classic 1916 book on capitalist imperialism, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, Vladimir Lenin quoted a debate surrounding a proposed transport trust in Berlin, observing that “traffic interests became interlocked with the real estate interests of the big bank which financed it [...] and this interlocking even created the prerequisites for the formation of the transport enterprise.” It’s no wonder that this historical “struggle for economic territory” extends to the virtual realm today and in Cline’s future. One of Fredric Jameson’s most powerful observations about science fiction in Archaeologies of the Future is that “the distinctiveness of [science fiction] as a genre has less to do with time (history, past, future) than with space.”

In Cline’s universe, virtual reality cannot escape the economic and political confines of the real world. This is why Watts was actually stuck on Incipio, the planet where all avatars spawn—a boring place filled with “giant virtual malls that covered the planet.” Because it’s the default spawning location for new players, and since transport fees are out of reach for many, the vast reaches of the OASIS go unexplored by millions. The mall-planet Incipio lends credence to artist Sze Tsung Leong’s prediction in The Harvard Design School Guide to Shopping that “[i]n the end there will be little else for us to do but shop.”

This fictional virtual reality also runs the risk of becoming a natural conclusion to today's image-driven big tech trajectory. As Guy Debord famously observed, “the final form of commodity fetishism is the image.” Before even announcing the company was changing its name to Metaverse, Facebook employed 10,000 employees to work on virtual reality. A team was set up to work on what they call “the Metaverse,” which Mark Zuckerberg described as “an embodied internet, where instead of just viewing content—you are in it.” They believe this is the future, announcing at the time a $50 million investment in partnering with organizations solely to make the Metaverse “inclusive and empowering.” This was done to avoid the same mistakes Facebook has made as a social media platform, being justly blamed for creating a society of dopamine driven consumers and destabilizing democracies across the planet. Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen’s revelations linked the company’s exploitative methods to their profit incentive. Now Facebook has launched a public relations campaign to bury the whistleblower revelations and pitch the Metaverse’s virtual realm to the masses and investors. The revelations expose that the virtual world can never detach itself from the social conditions of the world in which it exists.

Physical Geographies

Ernest Cline’s Ready Player One—along with the subsequent blockbuster film of the same name directed by Spielberg (2018)—and Ready Player Two take place around 2050 in Columbus, Ohio. Rural areas in the United States have been abandoned due to energy and oil shortages, resulting in a vast migration to urban centers and their peripheries. Rural regions are considered no-go zones left to scavengers and adventurists, whereas urban areas offer proximity to jobs (although there’s mass unemployment and job shortages), safety from rural scavengers (but not urban ones), and access to limited energy supplies. Inequality is rampant. Safe, affordable housing is virtually nonexistent. Towers of stacked trailer homes are the norm.

In the books and subsequent film, Columbus is the new tech Mecca. The city is home to two tech giants: GGS, the company that invented the OASIS, and IOI, their main competitor. The OASIS is the core of the city’s economy. The corporate dominance is coded in the skyline, which is built around GGS HQ and IOI Plaza. Columbus is one of the safest and most technologically developed cities in this future US. Energy is abundant due to corporate money and security is prioritized to avoid any terrorist attacks on headquarters or main servers. It’s also one of the most expensive cities to live in. Yet billionaires’ mansions and luxury apartments tower in a city with extremely high rates of homelessness and destitution. The OASIS economy maintains a class of white collar workers, but it has also created a class of indentured servants through IOI’s loan programs. Indeed, many Americans come to prefer indentured servitude over the struggle to survive in the unequally developed economy. “They thought of it as job security. It also meant they weren’t going to starve or freeze to death in the street,” said Watts. One could see this used today as a malevolent justification for Elon Musk’s plan to make future Mars workers indentured servants.

Little has likely changed in the future economic segregation of Columbus’ geography. Downtown appears to remain out of reach for working class residents, reserved for skyscrapers and overpriced apartment blocks—especially due to increased security costs. In the book, Watts actually grows up in Oklahoma City; he’s only able to afford moving to “a slate-gray monolith on the banks of the Scioto” in Columbus after winning the first key in the contest.

His apartment in a repurposed Hilton offered a view of the skyline, but he painted the window black to focus on the contest. The window offered views of the GGS HQ, “a shining arrowhead of mirrored glass rising from the center of downtown,” and the IOI Plaza, “the three tallest buildings in the city,” made up of “two rectangular skyscrapers flanking a circular one, forming the IOI corporate logo.” The IOI buildings are “mighty towers of steel and mirrored glass joined by dozens of connective walkways and elevator trams.” It’s also telling that the companies choose skyscrapers when today’s tech companies tend to create vast horizontal research parks designed to make employees feel at home—or, to be more explicit, to abolish the differences between home and work so that employees are always at work. In the future, the vertically overbearing IOI Plaza reflects an implicit corporate move to control: indentured servants are held in the same buildings as white collar workers, organized hierarchically.

In the future, the upper class sectors of Columbus—places like Bexley, Upper Arlington, and Worthington—are fortified. This is especially the case in Columbus’ bourgeois suburb of New Albany, where OASIS creators James Halliday and Ogden Morrow build giant, ultra-modernist mansions on Babbitt Road. In Ready Player Two, Wade moves into Halliday’s mansion, “a giant house with over fifty rooms, including two kitchens, four dining rooms, fourteen bedrooms, and a total of twenty-one bathrooms.” Not strictly fiction, this inequality is already apparent when comparing present-day New Albany and Columbus. In the suburb, billionaire Les Wexner lives secluded in his 336 acre $47 million estate. In the city, 1,400 families go to court for evictions every month.

Science Fiction as Realism

As we poke around the neo-cyberpunk future of Columbus, it’s apparent that the city hasn’t drastically changed. In fact, based on its current economic and political conditions, it seems as though this is where Columbus is heading. As the philosopher Fredric Jameson observed, “cyberpunk is not really apocalyptic.” The genre is less about the end of the world and more about illuminating the dystopian implications of the present. Ready Player One is a testament to Columbus’ current conditions that point to its future as a postindustrial Mecca and climate refuge riddled with class antagonisms and inequalities.

Foremost among the factors contributing to Columbus’ complicated future is the annexation policy it adopted in the 1950s. As other industrial hubs like Cincinnati and Cleveland saw most of their white urban population flee to the suburbs—taking their tax revenues with them—Columbus was in a unique position. Since the city never saw the same intensity of growth as other cities with more direct transportation links, like the coasts and rivers around the Great Lakes, it never became an industrial hub. As white flight ensued, the almost untouched townships surrounding Columbus became the target of an aggressive annexation policy designed to keep tax revenues in the city by expanding the city limits.

Columbus officials offered new suburbs cheap access to city water and sewage, which the city had essentially monopolized, in exchange for annexation. This monetized white flight and kept revenues from new developments like malls within the city’s reach. It’s unsurprising, then, that Columbus birthed the retail billionaire Les Wexner. He kept his headquarters in Columbus and built his own suburb of New Albany, where, of course, the richest characters in Ready Player Two live. Wexner, postindustrial capital, and the city’s annexation policies contributed to making today’s Columbus a postindustrial hub whose economy and population are growing as many other cities in the region continue to decline.

The benefits of Columbus’ upward trajectory, however, never actually trickled down. Rich suburban school districts have avoided integration with Columbus City Schools, keeping schools segregated and withholding much needed funding. The annexation policy has also forced the city into a never-ending cycle of expansion often directed by private developers and rarely suited to the needs of working people who never saw the fruits of subsidized private development.

As we can see, Ernest Cline’s vision of Columbus in 2050 isn’t just the somber conclusion of dystopian fiction. It’s a disturbingly realistic future for the city. Columbus’ economy is currently shifting away from insurance and retail toward tech giants like Google, Amazon, and Facebook—all of which are building data centers in New Albany. Even local planning and transportation organizations have essentially given up imagining alternative futures. Their plans are shackled to those of private developers. In 2015, the Mid-Ohio Regional Planning Commission released its insight2050 report, predicting different paths of development for the city. Each path simply relied on past development trends like suburban sprawl and connected condo homes. Essentially, the report admits that Columbus in 2050 will look like it does today. The evidence points to the future development of Columbus following the process of the new Quarry Trails Metro Park. The Park was designed to boost property values for a mixed use development being built nearby. This public-private ‘partnership’ is a part of the ‘Columbus Way’—a doctrine of private direction for public funds and tax abatements. “We’ve become more intentional about it,” says Kenny McDonald, CEO of One Columbus. Instead of private developers building neighborhoods and towing publicly funded infrastructure and tax abatements behind it, the future of development will be defined by publicly funded projects built alongside private mixed use development.

If strip mall apartment blocks are the best we can come up with—and in Columbus this undoubtedly is the case—then what do those who can’t afford to live in those apartments have to look forward to? History today has become, as Fredric Jameson put it, “a History that we cannot imagine except as ending, and whose future seems to be nothing but a monotonous repetition of what is already here.” With such a lack of spatial imagination, it’s no wonder that billionaires today throw money at not only virtual geographies like the Metaverse and social media, but also towards colonizing Mars; anything to maintain current social and economic conditions by avoiding confrontation with their unsustainable contradictions.

The virtual and real geographies in Ready Player One and Two, and in most of cyberpunk, are not entirely science fiction. In 1989, Fredric Jameson wrote in Postmodernism Or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism that science fiction offers “an ultimate historicist breakdown in which we can no longer imagine the future at all, under any form—Utopian or catastrophic.” Within these terms, Jameson concluded that “a formerly futurological science fiction (such as so-called cyberpunk today) turns into mere ‘realism’ and an outright representation of the present…” The dystopian realism of cyberpunk emphasizes a need to take Marx seriously in his follow up to his famous quote about religion being the opium of the people. He claimed that abolishing religion did not mean banning churches or other direct suppression, but instead abolishing the “condition that requires illusions.” This would entail confronting the illusory happiness of the OASIS or Facebook’s Metaverse through addressing the wider economic and political conditions that “require illusions” in the first place.

The lesson in Cline's Ready Player One and Two stems from its essential lack of imagination. The genre of cyberpunk cannot answer the open question: what happens the day after the revolution? Instead, it’s a genre that projects the shortcomings of late capitalism into the future. Cline’s Columbus cannot escape the inequalities and antagonisms that define it today. His city of the future is characterized by a deflated spatial imagination of the present. This is not so surprising—what is there to imagine when private developers hold all of the power in planning our spatial future? Jameson offers a way out, which involves both time (the future and history) and space (new urban and geographic plans):

The problem is then how to locate radical difference; how to jumpstart the sense of history so that it begins again to transmit feeble signals of time, of otherness, of change, of Utopia. The problem to be solved is that of breaking out of the windless present of the postmodern back into real historical time, and a history made by human beings.

Reading Ready Player One and Two effectively requires resisting both romanticization and cynicism. The nostalgia for 1980s cultural references is just as unproductive as a nihilism towards culture that’s critical of capitalism. Instead, the world in which Watts moves must be understood as a testament to the dire need for change. Cline’s Columbus of 2050 isn’t science fiction, but a form of dystopian realism based on our current and historical conditions. This dystopian realism should be used to fuel a fight for imagining and, most importantly, working towards new futures for Columbus.