Awe Studies: Resisting Awe

This piece is part of a series that responds to the theme of the 2024 Cleveland Humanities Festival: “Awe.”

To be a writer is to be in love with humanity and to love humanity is to never cease to be equally amazed by its greatness and frivolities. In a world where the future that we were promised is nothing more than the past at greater speed and with a shinier coat, our lives seem to be a typhoon gaining intensity with each invention. It’s both wondrous and joy killing. We have been turned into walking paradoxes. To experience true awe and wonder, in such a world, seems to only be two things: an act of resistance or a surrender to lunacy.

I have found as an artist that awe is a tool of resistance, even when it threatens to push me to lunacy. There is a clarity that comes with embracing the tumult of life that allows art to do more than represent reality but imagine futures beyond our current condition. Most of today’s art, it seems, spends too much energy escaping the tumult that, by the time it finally rids itself of it, leaves imagination bereft. It’s as if the fruition of art should be chaos-free, should leave nothing open. A very unfortunate disposition, for without imagination—the engine of awe—lasting change is very unlikely.

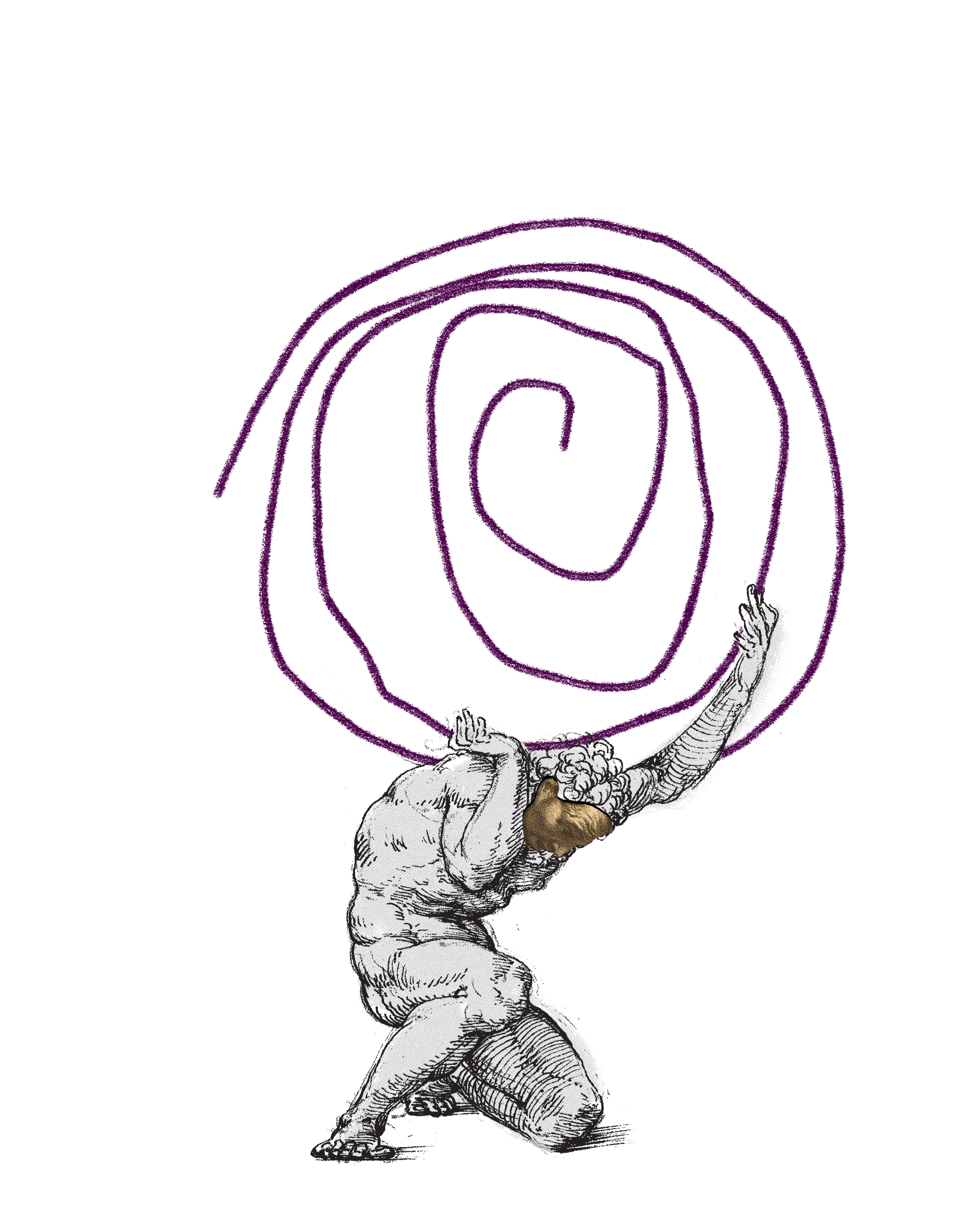

In his essay, The Myth of Sisyphus, Albert Camus concluded that the gods condemning Sisyphus to ceaselessly roll a rock to the top of a mountain, only to have it fall back over and over, should not be thought of as punishment. “The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy,” he wrote.

One might argue that it is easier for the onlooker to imagine Sisyphus happy than for Sisyphus to imagine himself happy. There is nothing in rolling a rock that is inherently happy, nor is it “normal” or sensical for one to be happy looking at another toil ceaselessly or for one to be happy about toiling incessantly. Yet, we can agree with Camus that happiness is possible here. Happiness, then, does not depend on the act or actors.

Awe is similar. Nothing is intrinsically awe-inspiring. Yet, if nothing is awe inspiring and awe exists, then everything could be.

As I am writing this, tears are rolling down my cheek and I cannot stop them. God Save Texas—a three-part Max (formerly HBO) TV documentary series directed by three Texan directors and based on Lawrence Wright’s book—is playing on the TV. The first episode directed by Richard Linklater is about the prison system in Huntsville, TX. I am bewildered by how terrible we are to others, by our indifferent disposition toward people behind bars.

My tears are sentimental and worth nothing more than the half-cooked theory I just laid out about happiness. Yet, the joy of the family reuniting with their loved ones coming out of prison is real. Their laughter, hesitant hope, and tears are real and awe-inspiring.

Awe is a kind of surprise that resists pity or cynicism. It is not relative or subjective. It’s an active and dynamic process that cannot be separated from its twin concept, wonder. True awe is not possible without questioning its essence. In absence of examination, what we call awe, surprise, or amazement, can at best provide a futile and temporary respite, while other times, to our own detriment, we can miss the awe of a situation completely.

•

For some reason I never cared to investigate, Anthony Bourdain reminded me of Simone Weil. No other individual, I think, embodied Weil’s two most important tenets—affliction and attention—as Bourdain did.

In his No Reservations series, the episode in Haiti (season 7, episode 1) was my favorite, but the one that affected me the most was the Nicaragua episode (season 7, episode 3). In it, Bourdain and his crew visited the city of Managua and met with Hector, who took them to La Chureca, a garbage dump where some 300 families, goats, and dogs scavenged for food. The scene required attention for both the viewer (me) and Bourdain. I became aware of the voice over. Only seconds after Bourdain jovially pronounced the term Churecarios through the voiceover, the camera turned to face him in a scene. Adorning dark rectangle sunglasses, he spoke in a grave and halting tone, bemoaning having shoved food in his mouth just hours before at a nice restaurant.

Witnessing people at the Chureca accentuated by Bourdain’s reaction was the most heart wrenching thing that I had ever seen. And believe me, I have seen poverty. I have lived in poverty most of my life. Bourdain could not believe what he was watching either. His face contorted in pain. He was on the verge of crying. His jaws tensed, anger flashed behind his eyes, and his lips quivered. Pity, which one can see on his face, had left little space for surprise and even less for deeper inquiry. He asked to leave. I paused the clip and stood up.

In the episode in Haiti, while visiting Port-au-Prince with a Haitian actor, Bourdain visited a street food vendor. Children, mostly young boys, crowded around him. They were happy to see the foreigner and the cameras. I could feel their joy and their acting for the camera. I could also see Bourdain’s discomfort. He decided to buy them all food. Soon a crowd gathered, and people started fighting. In a behind-the-scenes conversation, he described this scene as one of the most heartbreaking that he had done. While that made sense to me, and I could see how a foreigner would feel this way, I did not think it was as bad as he made it out to be.

The kids were happy. They were hopeful. They were among friends and in control of themselves and their surroundings, at least at first. In short, they were humans. I recognized myself in them, therefore they never appeared helpless or as lost causes. I never once pitied them as I did the Nicaraguans. This amazed me.

Why had I never extended this same humanity to the Nicaraguans? I pitied them, and I only saw and reduced them to a single image from an hour-long curated TV show episode. This realization forced me to catch myself, a moment of awe. The Churecarios were artists, fathers, mothers, aunts, uncles, friends, thinkers, and people with full lives.

I was left worse off by my narrow understanding. I was only moved by the situation of the people at the Chureca but not by them as people. Pity is only conditioned by situations, whereas surprise, true awe, comes from recognition, the act of witnessing. Weil and Bourdain, I believe, were two philosophers for whom the act of witnessing was imperative. They bore witness not to show the exterior world, but to find who they were by showing us our shared humanity.

•

A year ago, my then-supervisor—the best boss that I had ever had—shared the weekly themes for the upcoming season for the institution where we worked. As the literary arts director there, themes guided my choices for the lecture series. The theme he wanted my advice on was Awe and Wonder. My mind went to work, thinking which author I would bring for my lecture series for that week.

My first choice was Mark Fisher for his book Capitalist Realism. However, for the books we selected, the authors had to agree to give an in-person lecture. Since Fisher had passed away years ago, and during my second season I had selected an academic book on nonviolent movements that was not well-received, I proposed to invite two celebrated poets whose works focus on wonder and delight. Unfortunately, I left the position before I could send them the invitations, but I keep thinking about this decision.

While the poets’ works are powerful and thought-provoking, I knew their analysis of awe and wonder could not compare to Fisher’s, and I felt deep shame and anger that even if I could invite Fisher and he could join, his would be the least attended lecture of the season, mostly because our understanding of “awe” and “wonder” dictate that we should do something rosy, beautiful, and most importantly, fun. That realization bewildered me, and I was amazed by my own cynicism.

The part of Capitalist Realism that came to mind was Fisher’s discussion of the thesis of Cuaron’s 2006 film Children of Men, which he articulated in two questions. First, how long can a culture persist without the new? And second, what happens if the young are no longer capable of producing awe?

Fischer spent the rest of his writing life trying to answer these questions. They are important questions, however they never sit well with me. I do not believe that we should aim to produce awe. Instead, we should stay open to its happening, and we should wonder. Wonder about what? The answer is where I think true awe, not enlightenment, resides.

There is a strange bewilderment, not necessarily joy or knowledge, that comes with wondering about past, present, and future situations that, in normal circumstances, frustrate or escape one’s attention. The act of pondering these situations is the beginning of awe itself, or something that can lead to it.

Fisher’s questions require explanation and production of a result, which has the potential for awe. Like enlightenment, we ought to accept it when we understand it, when we make sense of it. But awe, for me, is different. It seeks not to explain but to stumble upon.

This, therefore, turns Fisher’s question about what happens if the young are no longer capable of producing awe into a source of awe. The medicine for such an eventuality resides in its destruction. Awe is not something to produce, but to witness. Any attempt to produce it, even when successful, will undermine it.