Play Acts: or, How I (Actually) Survived a Zombie Attack

This piece is part of a series that responds to the theme of the 2024 Cleveland Humanities Festival: “Awe.”

SECOND COP: I tell you, it’s no picnic.

It’s a cold, wet day in the ass-end of nowhere, Spain. The ravens are circling above, and I think the wolf I rescued from the beartrap—a trap that was surely meant for me—is now stalking me. I keep one hand hovering over my holster at all times, but it’s not my safety I’m concerned for; it’s the safety of the president’s daughter, who I’ve been hired to protect.

But first I have to actually find her.

The nearby village, Pueblo, is in flames by the time I arrive. No, not the whole village—just a cop, burning on a pyre in the center of the village square. And not just any cop—my cop, one of the two who brought me here. Four villagers tend mindlessly to the fire, stabbing their rusty pitchforks into the hay; they call these zombie-like people Ganados. Cattle. I want to think of them as victims, not enemies, but that’s tough when they’re trying to kill me—they’ve already tried once. They almost got me, too, if you can believe that. What can I say? I wasn’t prepared to just start shooting the locals.

Now I’m prepared for anything.

Still, there’s four right there, and who knows how many more inside the darkened houses. It’s not like I’m looking for a fight. I decide to sneak past them; there will be plenty of shooting later, I’m sure. I hug the outside wall of the nearest building and make me way to the left of town, but I hardly walk two steps before I find myself staring at the back of another mindless Ganado, the barrel of my gun mere inches from her neck. I have no intention of shooting her. Be cool, I tell myself. It’s just like high school—be cool, or they’ll eat you alive. I lower my gun and, with hands so steady I could circumcise a fly, unsheathe the bowie knife from my body harness. One quick cut. She won’t even know it’s coming.

Someone yells. “Agarradlo!” Grab him!

I jump back from the woman and spin around, keeping my head on a swivel. I clock the spotter on my six—an old man, yelling from a nearby roof, waving an ax at me. No, not at me—towards me! I duck just in time, the bloody blade flying harmlessly past my head, and draw my 9mm from its holster without ever taking my eyes off the threat. I cradle the gun in both hands just like I learned with my dad shooting paper targets back home in North Mississippi, employ the old salesman’s trick—“just look between their eyes”—and pull the trigger.

Headshot.

No time to celebrate. There’s still the woman to contend with, and now the villagers from the square have joined us, armed with their pitchforks and sickles. I pull a fresh magazine from my belt with my left hand, load it into my gun, and chamber another round. I remember what they taught us back in gun safety classes in North Mississippi: it’s safer to escape than to confront. So I make a break for the nearest door, turn the knob, slip inside, and slam it shut behind me. The lock won’t hold them out for long. Maybe this dresser will help, I think, pushing it into place behind the door.

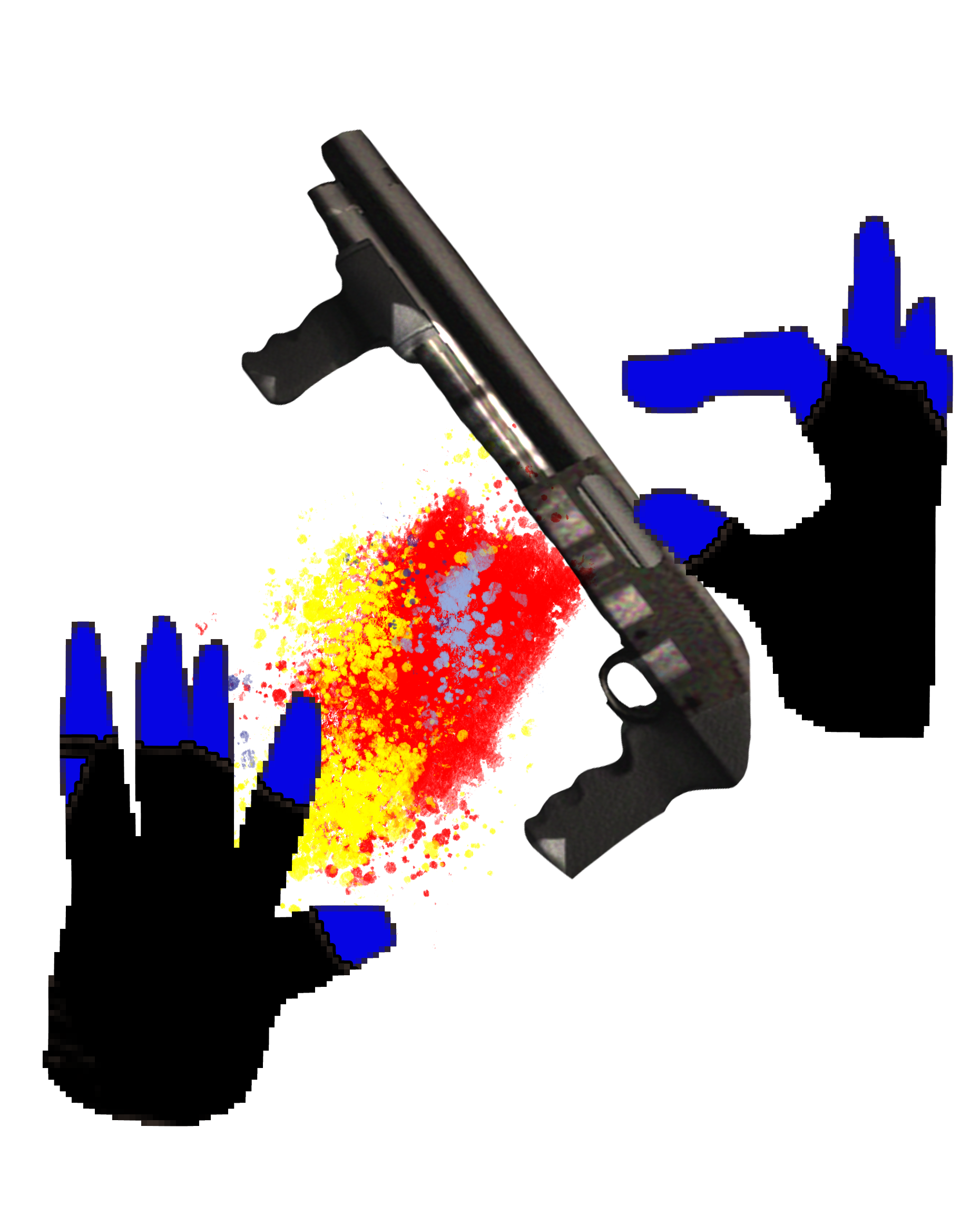

I raid the place. Downstairs there is nothing but some potted herbs (which I take; I might be able to make something useful out of them) and gold coins, but upstairs I hit the jackpot: a 12-gauge pump-action shotgun. I crouch beneath a window overlooking the square and rack my new weapon, hoping to scare off my assailants with the sound alone (another North Mississippi gun safety lesson), but all it does is draw more attention to my position. I peek through the glass and count nearly a dozen heads. Now I’m really starting to sweat. Where did they all come from? What am I supposed to do about it?

I know what to do.

Shortly before my father killed himself he started saying something I didn’t understand at the time, but it made him smile, so I smiled too: just blow all the bastards to hell.

I didn’t know what he meant then; I think I understand it now.

I swing my new street howitzer over the windowsill and get ready to blast.

Except—oh, God! One of them got inside somehow. He’s right behind me! He picks me up in a bear-hug like I’m a child and starts squeezing the life out of me. I struggle—I try to shake him off—I give it everything I’ve got—but it’s useless. My body fails me: first I lose control of my limbs, and then I lose my senses entirely—my vision goes, the sound of snarling zombies goes silent, and I feel nothing but my own sweat growing cold on my skin.

I’ll get ‘em next time, dad, I say, going down.

•

LUIS SERA: Being a hero isn’t what it’s cracked up to be anymore.

Believe it or not, nearly all of that—the crouching, the sweating, the shooting—actually happened to me.

Narratively speaking, I was role-playing on my Oculus Quest 3 as the protagonist Leon Scott Kennedy, hero of Capcom’s Resident Evil 4 VR (written and directed by Shinji Mikami), roaming the same patch of woods over and over as I learned how to survive the secrets of Los Illuminados and their zombifying parasitic arthropods, Las Plagas.

Physically speaking, however, I wasn’t role-playing survival action—I, Daniel, was actually surviving. Dodging, crawling, dashing, drawing, loading, aiming, stabbing, pin-pulling, throwing—the various “fabula” (the underlying, constitutive events) of Leon’s “story”—of which Resident Evil 4 VR is the “text”—existed on a one-to-one basis with the real-world actions of the reader, me.

In narratology, or the study of narrative, there is usually a functional distinction between protagonist and reader, a distinction that depends on the fabula-story-text as just described: a protagonist’s actions make up the fabula of a story, which the reader accesses through the text. Even in a “Choose Your Own Adventure” the reader is not an agent of change within the story in the same way as the protagonist is, nor do the actions of the protagonist, outside of key textual choices, map with the actions of the reader.

While literature has always been interested in troubling this distinction (from the metafiction of Don Quixote to the aforementioned CYOA), virtual reality games like Resident Evil 4 VR nearly collapse it altogether. When you dodge an axe in VR, you dodge an axe in real life, at least as far as the embodied experience of the player is concerned. The player’s reader-body becomes intimately connected to the game’s protagonist-body in order for the text itself to exist.

In the twentieth century, language philosophers like Rudolf Carnap and A. J. Ayer explored the idea that all sentences must be true, false, or nonsensical, based on a verifiable relationship to the reality that they faithfully (or not) described. But some sentences, as J. L. Austin pointed out in How to Do Things With Words, don’t seem to describe a reality at all; they actually create one. For example, while the meaning of a sentence like “I am getting married” is meaningful (true or false) based on its relationship to reality, actually saying the sentence “I do” performs its own meaning. Austin called such sentences performative utterances, or “speech acts.”

Likewise, video games like Resident Evil 4 VR require a kind of reading that doesn’t just describe what happened in a story, but actually performs it. The only way to read the story is to play it, and the only way to play the story is to do it, to completely embody it. Pushing the parallel, we might call these kinds of readings “play acts,” where assuming the role of a protagonist—reading a story by physically playing it—is an act of embodied performance, not abstract description. If you want to make that headshot, you better be able to hold your hands steady in front of your face. If you want to read a hero’s journey, you better start acting heroic. To riff on another philosopher, Berkeley, as he riffed on Descartes: esse est ludere.

To be is to play.

•

LUIS SERA: You’re… not like them?

LEON: No.

I’m not the kind of person who usually gets to play the hero in life.

As a misfit in the 1990s I grew up reading books, watching movies, and playing games, many of which suggested there were other worlds altogether for people like me. All I had to do was grow to the right age, read the right sentence, or fall down the wrong hole and I would be magically transported to a world where I really mattered—my own private Isekai, as the genre of “other worlds” is called, where my weaknesses would become strengths and my strengths become superpowers. Where was my letter-by-owl, and what was my digi-destiny? How many spines did I have to break before I discovered my own Ivalice, my own Narnia, my own Fantastica?

But reality is not a book, and the only spine I broke was my own—as a passenger in a car accident in 2008. I blacked out upon hitting a pear tree and was magically transported to my own private room at a trauma hospital in Memphis called The Med, where I was stitched, glued, and screwed back together over more than a dozen surgeries in as many months. I broke the right side of my body, including a back fusion and extensive nerve damage from a broken spine. I wasn’t paralyzed, but the doctors weren’t sure how much walking I had in my future.

Bedridden and immobile, my dad bought me an Xbox 360 and a copy of Elder Scrolls V: Oblivion. Oblivion is an RPG that is played with a single controller, and my broken thumb healed much quicker than my broken back. With minimal bodily input as a reader I was able to output maximum ludonarrative action in the protagonist, a kind of immersion that might best be described as “out-of-body.” My body and the Hero of Kvatch’s body had nothing in common. In fact, much of the pleasure came from leveraging that physical distance between us—one of the classic appeals of heroic fantasy.

Eventually I was able to move from a bed to a wheelchair, then from a wheelchair to a cane, and for a decade now I haven’t even needed the cane. But the cost of such mobility is pain, a pain like the parasitic Las Plagas that threatens to take over both my body and my mind. When I turned 33—the age Jesus Christ was when he Isekai’d into Heaven—my pain was so persistent that I became bedridden again, which only made the situation worse. I laid down because my back hurt, and my back hurt because I laid down. So, following my late dad’s model, my mom bought me an Oculus Quest headset for my birthday, hoping to get me out of bed and moving again. And, in pain but moving again, I downloaded Resident Evil 4 VR.

Where Oblivion exploits the physical distance between its reader and its protagonist to provide the “out-of-body” immersion of heroic fantasy, Resident Evil 4 VR collapses that distance, demanding of its reader the deeply “in-the-body” immersion of body horror. Pressing buttons on a controller upholds the reader-protagonist distinction at a mechanical level, while the embodied mechanics of VR, by making input and output literally the same action, weaken the distinction. Story has always been a bodily experience—the eye of the reader, the thumb of the gamer—but the potentially full-body “play acts” available to VR (which depend on individual accessibility needs, and are not always essential) are where the body of the hero-protagonist becomes the body of the reader, making the reader an actual hero.

#

OCCULT LEADER: (laughs) Soon, you will become unable to resist

this... intoxicating power.

A consequence of Austin’s attempt to widen the taxonomy of language was, in effect, a taxonomic narrowing—what if all speaking was ultimately an act of doing?

Is all gaming, likewise, play acting?

Oblivion has been modded for VR and Resident Evil 4 was originally a GameCube game, played on a controller. The distinction between them for play acts is mechanical, not narrative, and those mechanics can be adjusted at will in Resident Evil 4 VR. Field of view can be adjusted for motion sickness, motion itself can be toggled between physical walking movement and joystick movement (gliding or teleporting), weapons can be accessed on your body or through a scroll-wheel, and you can still play the entire game sitting down entirely if you want or need to.

This suggests a difference of degree, but not kind, between a VR game and its non-VR counterpart, in which any given playstyle sits somewhere on a broad, flexible spectrum of “act” vs “description.” Especially when we move beyond mechanical differences and back into narrative differences, into bodily, psychological, and emotional play acts beyond merely aiming and jumping—for example, something like empathy, even when there is no human per se on the “other side” of the technology (what Jade E. Davis, in The Other Side of Empathy, calls one-sidedness). The question might be: if we are acting something out in the real world when we play, then what are the narrative consequences for reality?

Children perform play acts all the time, but without a corresponding text—we call it pretend. A play act is a mediated form of playing pretend, which requires mediation technology: a book, a movie, a VR headset. Pop psychologists like Steven Pinker have gone so far as to call fiction an “empathy technology,” while Roger Ebert famously called movies “empathy machines.” However, as Davis points out, mediated empathy, when successfully deployed, may simply be an illusion that comes at the expense of the already-disenfranchised in order to shore up the power of the status quo; it dehumanizes the Other and alienates the Self.

This is one reason why VR technology can be viewed with such skepticism by many social scientists, from disability studies scholars to race studies theorists. The body that performs the play act carries a risk similar to that of mediated empathy: if the world/body of the reader and the world/body of the protagonist are, by doubling up, effectively collapsed, are one (or both) effectively erased as well? The world of the game is, like all texts, bound and limited, boundaries and limitations that reality itself is not supposed to have. Is a play act a limiting of the player’s world, or an expanding of the textual world? Are there right games to play and wrong ones, and does the reader have the choice? And what’s the difference when the actions themselves are the same?

Even if I could answer these questions myself (I can’t), I don’t know how much it would matter. I have always loved a good story, as a disabled adult more now perhaps than ever. As long as games like Resident Evil 4 VR exist I will probably play them. And the better I play, the better I am, the better the story will be. As the villain Ramon Salazar will tell you, should you choose to face him:

LEON: I don’t ever remember being a part of your crappy script.

RAMÓN SALAZAR: Well then, why don’t you show me what a first-class script is like…

Through your own actions!

•

LUIS SERA: Okay… It’s game time.

I slip into Pueblo for the second time with my gun in my hand and a smile on my face. I know how lucky I am to get a second chance, and I don’t intend to waste it; I intend to press my luck. I must protect the president’s daughter.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m no toady; I don’t care about the president. But I was hired to do a job, to protect an innocent person, and that’s what I’m going to do.

No more sneaking around.

Blow all the bastards to hell.

I run in, shooting, aiming straight for the heads. I drop the four Ganados in the square before they even know I’m coming, looting some extra rounds off their corpses just in time for the axe-thrower on the roof to take notice. I duck inside the nearest house, block the door with a dresser, and run upstairs to the shotgun. It’s déjà vu all over again. But this time I do things differently. I take action. Rather than hide in the corner and wait to die I fire a blast through the window and dive through the breaking glass, falling calmly to the ground. Behind me, a chainsaw revs; ahead of me, the gates out of the village. I choose the gates.

But they’re locked! And now the path behind me is blocked by the Ganado with the chainsaw, a cloth sack tied over his head—and a dozen more Ganados behind him.

Shit.

I empty my shotgun and drop half the mob, including the chainsaw man, but he just gets up again as if nothing happened. Shells spent, I toss the useless shotgun and draw my trusty handgun, unloading into his chest, but he charges through the lead like so much thrown sand. I load up one more magazine—my last—and then grab my bowie knife, blade in one hand and gun in the other. We face off like two swordsmen. I may not make it out of here alive, but it’s not going to be bag-face that takes me. He raises his chainsaw; I lower my knife; we rush each other, swinging.

I slice first. There is no second slice; down goes the heavy, dropping his chainsaw harmlessly at his feet.

A church bell rings above the fray, as though calling time-out on the fighting. Indeed, the fighting stops. The rest of my assailants seem to forget about me entirely, retreating one-by-one across the square and into their chapel. They leave me where I stand, and I can stand only barely. My breath is short, my blood is pumping, I’m not drinking enough water—but these are all good things. These are signs of life, if nothing else. And what else is there—but life?

And, between breaths, I am smiling, because I know now that I can really do it—I know how to do the one thing that my father, at the end of the day, couldn’t figure out how to do.

I know how to survive.