Told by an Idiot: On Jaroslav Hašek’s “The Man Without a Transit Pass”

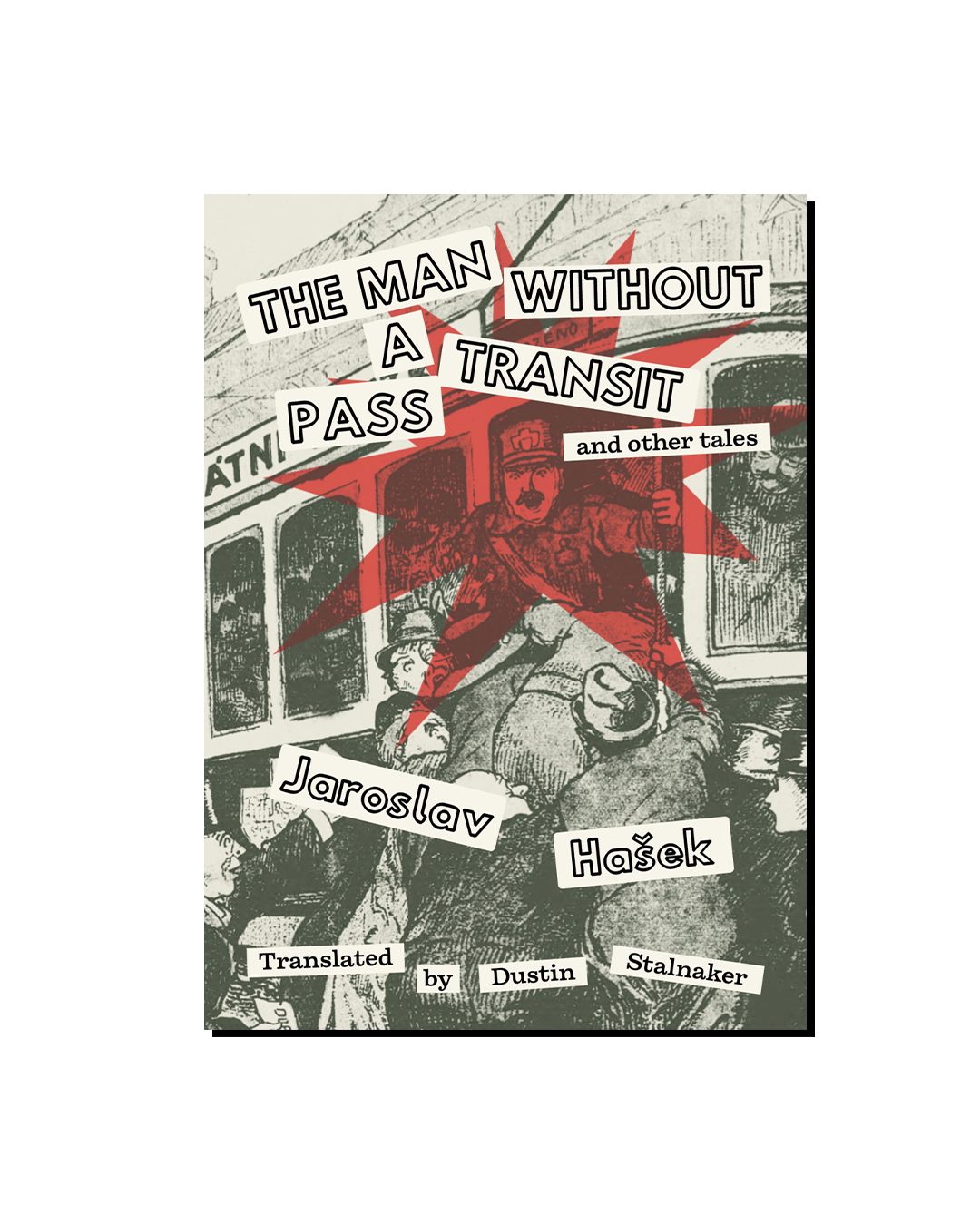

Jaroslav Hašek, transl. Dustin Stalnaker | The Man Without a Transit Pass | Paradise Editions | May 2023 | 148 Pages

Literature has a long and beautiful tradition of celebrating idiocy. Literary fools walk through the world without being formed by it, so that their mere presence in a story comes to feel like a judgment on everyone around them. Think of Dostoevsky’s Prince Myshkin, whose weakness before even the most benign forms of daily iniquity drives others furious—and him mad. So, too, Faulkner’s Benjy, protected from the rot at the heart of the Compson family by his own inability to recognize it. While other characters struggle to reconcile their knowledge of how to operate successfully in the world with an uneasy sense of how that world ought to be, literary fools exist in another realm, floating through stories that might batter and damage their bodies but cannot corrupt their souls.

The fool’s counterpart is the clown, a figure who paints his face into a grotesque mask of human emotion, inflating the stuff of everyday life to absurd proportions. Consider Ignatius J. Reilly, or Satan, or, perhaps, Jaroslav Hašek. Born in Prague in 1883, Hašek spent his decadently short life thumbing his nose at state, religion, respectability, and general good decision making. He was, in turn, a hard-drinking bohemian, an anarchist, a journalist, a humorist, a soldier, a turncoat, an anti-Bolshevik, a Bolshevik, and a revolutionary, returning to Bohemia and bohemianism in time for his death in 1923 of heart failure, perpetually drunk, grotesquely obese, and not even forty years old.

Significantly, he was a writer of nearly graphomaniacal output. Hašek is most famous for The Good Soldier Švejk and his Fortunes in the World War, an epic comic novel about an imbecile which has become, improbably, one of the best-known books in Czech literature. Winding and episodic, it tells the story of the guileless Švejk who says exactly what he thinks and finds himself twisting in and out of trouble, over and over again, falling into the grip of various authorities—in prisons, asylums, armies—only to slip through their fingers by dint of his simplemindedness. Like most great comic figures, Švejk cannot see how he appears to others and is unable to follow the most basic social protocols. He rambles from one misfortune to another on his way through the war and yet always survives. In this insane universe, the idiots will inherit the world.

Hašek wrote the book in less than a year and a half at the end of his life, and dictated when he could not write anymore. Yet at nearly 800 pages, only three volumes—or about half of the intended story—had been completed. Blasphemous and obscene, it made Hašek posthumously famous, and in the century since his death has been published in more than fifty languages.

He also wrote reams and reams of stories, essays, reviews, and reports for magazines throughout Austro-Hungary and Czechoslovakia, few of which have been translated into English. Thankfully, Paradise Editions has begun to close that gap. Founded by translator Matthew Spencer, the new press specializes in international literature, and The Man Without a Transit Pass and Other Tales is their first publication. It makes sense they would launch with a man as simultaneously cosmopolitan and provincial as Hašek, whose work puckishly attends to the minor, the crude, while reaching out into history.

Translated from German by Dustin Stalnaker, The Man Without a Transit Pass collects stories originally published between 1902 and 1921 in the various papers and journals through which Hašek made his living. There are stories here about life in Prague, reports from the provinces, satires of the imperial bureaucracy, and many, many reports so secondhand they feel like gossip. In the title story, a man boards a tram, but cannot buy his ticket in time when he suddenly feels “a human stirring in his bowels.” (A surprising number of these stories turn on the subject of shit.) The state spends thousands of crowns (about 2000 times the initial loss) to bring this truant to justice. “A new fare hike,” laments our author, “therefore seems inevitable.”

The main mode here is absurdity, layered thick with irony. A rural priest grows so addicted to his homebrewed green vodka that he falls into a kind of alcoholic paganism, spending all winter worshipping the summer he tastes in every drop. A group of monks feasts on the fat of the land and pays their pious servants nothing. Our narrator crashes in the house of a local notable and has to race clear to Albania to escape his captors. He writes in a knowing, chummy tone, slyly commenting on the absurdities of provincial life for his urbane audiences.

Hašek seems most interested in how systems distort the people inside of them. Whereas Švejk’s idiocy allows him to drift through his circumstances, his misfortunes sliding right off his smooth brain, in stories like “A Guest in the House” and “The Apprentices,” worldlier characters shatter when their codes of conduct cannot be fulfilled. Many of the volume’s stories end in suicide, or the sanatorium.

“The Story of a Respectable Person” (written in 1914) tells us of a certain Mr. Havlik, who wants nothing more than to be a good, pious citizen. Or rather: to never trespass “in any way against societal mores and public order,” a code he pieces together from newspaper columns and self-improvement tracts. The joke is that no one else seems to care about these rules at all, and his desperation to abide by them leads to disaster. Terrified that his fly might have come unbuttoned in front of a young woman, Havlik leaps from a moving tram, breaking his leg in the process. When he notices that a fellow diner is improperly eating with a knife, he visits the man at home to educate him on proper etiquette; he is rewarded by being thrown down the stairs. When he admonishes a fellow passenger on the tram for whistling, the whole car berates him. In the story's final and most tragic episode, one day while out for a walk, Havlik steps in dog poop, only because he was once counseled that “it is most indecorous to walk with a sunken gaze, for it gives the impression that one is looking for stray coins, which is a sign of avarice.” Upon complaining to a nearby police officer, he is ignored, and then threatened, and, when he appeals to the gathered crowd, they have him arrested. So Havlik returns home, writes an apology note, and gasses himself to death, begging the public’s forgiveness for his faux pas.

Hašek is mocking authority and bourgeois respectability, of course, but the criticism is ultimately of the individual’s inability to tolerate being the butt of a joke. If the universe is absurd, then we shouldn’t be so foolish as to take it seriously. Throughout the collection, Hašek’s narrator appears as a kind of merry prankster, a goofy bohemian willing to mooch off everything and everyone, from monks to officials to local notables foolish enough to buy his outrageous stories. In his own life, Hašek’s irreverence made him a poor fit for every ideological guise. He was a dissolute anarchist, a jolly communist, and a cowardly soldier who turned coat on a dime. He had the glutton’s disdain for indulgence, and his satire is never sharper than when cutting other decadents down to size, as if their hypocrisy were somehow worse than his own. In his stories, at least, he doesn’t pretend to be anything other than a conman; if his victims are willing to buy all those tall tales of noble beginnings and vast inheritances, then hey, that’s their problem.

In fact, as this collection went on, I began to get the sense that Hašek would have considered me an idiot for reading him. Between their military adventures, barrel-scraping lifestyles, and jolly obesity, Hašek and Švejk share so many qualities that we might want to conflate them. But Hašek is far too canny a character for that. (Whether Švejk is only pretending to be an idiot is another question.) Compared with his nostalgic counterparts in Vienna, he had no love for the Empire, whose bureaucracy and pieties he ruthlessly satirized. In the Prague of Hasek’s stories, even a system for saving people attempting suicide becomes a muddle of chest-thumping corruption. In one 1912 story, an abandoned camp latrine comes to stand in for all the faded marital glories of this declining empire, a holy site sacralized by all the shit that once flowed through it. One day, a major who once served at this exact camp views it while on a hike, and feels a sudden, nostalgic rumbling in his bowels. Yet when he arrives at the latrine, he finds another hiker already perched upon the beam. To see a common man in this once-noble shithouse breaks the major’s heart, and he falls down dead from sorrow. The other hiker picks up the dead major’s wallet and heads on his way.

Still, Hasek's writing gives us the feeling of something having been lost, of the whole shattered—as it was again and again across the course of the 20th century. He lived in a time when borders were not as important to individual citizens as to the governments responsible for them, and he tramped freely across a vast empire, passing through cities and towns which were soon to become landmarks of total war. His Prague was Czech, German, and Jewish, and he wrote in German when in Russia. His work was popularized outside of Czechoslovakia by the Prague-born Jew Grete Reiner, and Stalnaker notes that her German translation of Švejk “served as the basis for the earliest translations of the novel into other languages”—a cosmopolitan process Stalnaker continues with this volume. Reiner, like most members of Prague’s Jewish community, was deported to Theresienstadt, and killed at Auschwitz.

Hašek’s work testifies to this fracture, even if he never glimpsed the extent of it. I find it hard to imagine him surviving the Terror or the Anschluss, nor all the regimes that exiled absurdists and gassed the insane. He died young, before the various commissars and commandants could get to him. For a clown, there is always the curtain.